The Council of Trent defined acceptance of the sacraments as "necessary for every individual" and, by implication, defined their administration as the primary responsibility of the clergy. It labeled the Protestant view that "men obtain of God, through faith alone, the grace of justification" as "anathema."

The Council proclaimed the "seven sacraments are in such wise equal to each other," but that was not the operative view of them in Nuevo México. Baptism was the most widely accepted because even little children who "have not actual faith" were "reckoned amongst the faithful."

It was so important laymen were allowed to perform the rite with "true and natural water" in emergencies. This occurred five times in Santa Cruz between 1733 and 1759. Phelipe Romero baptized Juana Naranjo in 1739, Antonio Bernal blessed Juana Luiza Martín in 1745, and Julian Madrid committed Gervacio Duran in 1753. In 1753 Joanna Archuleta was baptized by necessity, as was Juan Domingo in 1758.

The fact the rite defined one as a member of the church’s community was seen as a form of protection against the Inquisition, which still existed as a threat. While the Council denied the act freed men from "the observance of the whole law of Christ," people seemed to think having their children baptized as they had been was sufficient evidence of their sanctity.

Men had the captives they purchased from the Comanche baptized. The friars argued this step alone made it impossible for Natives to return to their bands. The men who recruited their godparents instead may have wanted validation of the purchase and justification for the subsequent presence of hitherto unknown unmarried young men and women in their households.

The idea of baptism as protection was absorbed by the Jicarilla Apache, who were willing to submit to it in exchange for military support. That may have been the view of the Navajo who listened to Carlos Delgado and José de Irigoyen, but then rejected the corollary expectation they moved into pueblos.

The pueblos clearly saw baptism as an attempt to interfere with their traditional ways. In 1760, thirty years after Juan Miguel Menchero had decreed sacraments were to be administered for free to Natives, Juan Sanz protested any suggestion friars expected compensation. He wrote:

"In baptizing the children, it is necessary for the father to ascertain carefully when they are born, for if he does not, they do not bring children to be baptized, and if they had to pay an obvention, would they ever be baptized?"

The rite of matrimony probably was more accepted by those with property, since it and wills were the instruments that ensured the orderly transfer of assets from generation to generation. Others may have avoided the sacrament to elude interference by friars into their lives. The diligencias matrimoniales not only cost money but enforced prohibitions against certain kinds of marriages between kin not related by blood, like that between a man and his dead wife’s sister. Dispensations were possible, but added delays and notary fees.

The pueblos were more resistant because friars saw it as their duty to impose western concepts of family. Sanz noted, "if it is for obliging them to marry, this is done when they are discovered in concubinage, which is an invariable custom among them."

Carlos Delgado’s comments, quoted in the post for 24 February 2016, that friars had to travel at all hours suggested the more faithful accepted the need for "Extreme Unction." It was the only duty that required a priest to leave the precincts of the church.

The sacrament was merged with two others in these years, penance and the Eucharist, into the belief people needed to attend mass once a year, and to attend mass they had to confess once a year. This was clearly the doctrinal point behind Benito Crespo’s complaints discussed in the post for 3 April 2016 that many missions in Nuevo México did not meet this minimum.

Actual burial practices were rarely recorded. Angélico Chávez noted the burial registers didn’t begin until 1726 at Santa Cruz, Santa Clara and San Juan del Caballeros. The cover of the one used at Santa Cruz until 1768 was "limp tan leather." The flyleaf was "decorated with heavy scroll border, skulls, skeletons."

Deposition of bodies apparently was a private matter. In 1744, Menchero noted at Rancho del Embudo, where there were constant attacks by indios bárbaros, "The whole place is full of crosses." In 1776, Francisco Domínguez noted La Soledad, the settlement founded by Sebastían Martín north of San Juan, had "a little cemetery."

The pueblos treated death as a another aspect of their lives they wanted sheltered from clerical oversight. Sanz was correct when he observed people living in the pueblos "would die without confession and the father would not know about it," but probably misled when he thought "they would carry the body off to a ravine in order to avoid obvention."

Confirmations were rare. The Council of Trent had explicitly stated the sacrament could only be performed by a bishop. In 1760, Pedro Tamarón recorded he confirmed 96 at Embudo and that "they were prepared for it, and they recited the catechism." He did not mention performing the sacrament at either of the two local pueblos or La Cañada.

The seventh sacrament, the ordination of priests, was not practiced locally. This was the one the Council had in mind when it said "all (the sacraments) are not necessary for every individual."

Notes: On mission to Navajo, see post for 10 April 2016. I don’t know whether either group of Athabascan speakers saw some other value in having "water thrown upon" their heads. I haven’t found any comments of their beliefs prior to their contact with French and Spanish missionaries. Fees were discussed in the post for 27 March 2016. The use of skeletons and skulls as decorative motifs was mentioned in the post for 10 April 2016.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Chávez, Angélico. Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900, 1957.

Council of Trent. "On the Sacraments, First Decree and Canons," 3 March 1547. I’m quoting this since some things were changed by the Second Vatican Council held between 1962 and 1965. Some sacraments, especially penance, later acquired additional significance in northern New Mexico.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez in The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Menchero, Juan Miguel. Declaration, 10 May 1744, Santa Bárbara; translation in Bandelier.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 Novmber1760; translation in Bandelier. [Esp Hist I17] p475

Tamarón y Romeral, Pedro. The Kingdom of New Mexico, 1760, translation in Eleanor B. Adams, Bishop Tamarón’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760, 1954.

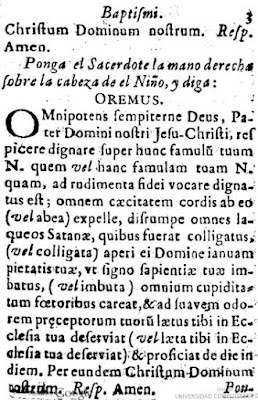

Graphics: First page on baptisms from Agustín de Vetancurt, Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, 1729 edition, discussed in the post for 1 May 2016.

Showing posts with label 07 Santa Cruz 16-20. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 07 Santa Cruz 16-20. Show all posts

Sunday, May 08, 2016

Sunday, May 01, 2016

Franciscan Traditions

Franciscan friars were literate men. They maintained sacramental books, kept accounts, and read letters circulated by their superiors. More important, they knew how to use the missals and manuals found by Francisco Domínguez in the churches of Santa Cruz, San Juan del Caballeros, and Santa Clara in 1776. They could decipher both Latin and Castilian.

One guide to administering the sacraments Domínguez saw in the Santa Cruz sacristy would have been in use in these years. The collection of Latin scripts, first published in Mexico City in 1674 by Agustín de Vetancurt, wasn’t superceded until 1748. The Franciscan editor was born in Puebla, worked with Nahuatl speakers, then wrote histories.

The first page of his Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos featured a woodcut of Santo Joseph with a dedication to him as guardian.

Joseph is mentioned as the husband of Mary in the Gospel of Matthew, which was the book that inspired Francis of Assisi to exchange earthly goods for poverty. Sometime around the year 145, the Gospel of James appeared. It described Joseph’s selection by the temple as the guardian of the adolescent Mary, in a tale reminiscent of Cinderella. All unmarried men of the House of David were ordered to bring their rods to the temple, where a sign from the Lord would identify the chosen man. It read:

"Joseph took his rod last; and, behold, a dove came out of the rod, and flew upon Joseph's head."

The book by Joseph’s son circulated in Greek manuscripts, but apparently not in Latin. In the early 600s the Gospel of Saint Matthew appeared in Latin, supposedly in a translation by Jerome. It elaborated on James.

"But as soon as he stretched forth his hand, and laid hold of his rod, immediately from the top of it came forth a dove whiter than snow, beautiful exceedingly, which, after long flying about the roofs of the temple, at length flew towards the heavens."

This gospel circulated widely. Brandon Hawke noted it moved into Anglo-Saxon tradition from the Carolingians in France. In 1260, an Italian Dominican, Jacobus de Voragine, included Saint Matthew’s story of Joseph in his Legenda Aurea. More than a thousand copies survive in manuscript. William Caxton published the Golden Legend in English in 1483. Alexander Wilkinson found a Castilian Flos Sanctorum published in the 1470s, a Catalan one from Barcelona in 1495, and Le Leyendo de los Santos from Burgos in 1499.

Voragine both simplified Matthew’s version, and embellished it:

"then Joseph by the commandment of the bishop brought forth his rod, and anon it flowered, and a dove descended from heaven thereupon."

The Council of Trent discouraged the interest in the legends of saints to promote factual biographies. Voragine’s text was republished in revisions by Alonso de Villegas in 1578 and by the Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneyra in 1599.

However, it’s the earlier image the Spanish shared with Caxton of the flowering rod that greeted the friars in Santa Cruz each time they opened the manual to read the baptismal language.

Notes: This James, better known as James the Just, was not the same disciple as James the Great, better known as Santiago. James the Just described Joseph as an elderly widow, which would have made himself the step-brother of Jesus.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez, The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Hawk, Brandon W. "Preaching the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew in Anglo-Saxon England," York Christian Apocrypha Symposium, 2015.

James. Gospel, translated by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Matthew. Gospel, translation by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Roberts, Alexander, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Ante-Nicene Fathers, volume 8, 1886; revised and edited by Kevin Knight.

Vetancurt, Agustín de. Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, first published 1674; woodcut from 1729 edition.

Voragine, Jacobus de. Legenda Aurea, translated by William Caxton, 1483; edited by F. S. Ellis, 1900.

Wikipedia. Primary source for history of the apocryphal gospels.

Wilkinson, Alexander S. Iberian Books, 2010.

One guide to administering the sacraments Domínguez saw in the Santa Cruz sacristy would have been in use in these years. The collection of Latin scripts, first published in Mexico City in 1674 by Agustín de Vetancurt, wasn’t superceded until 1748. The Franciscan editor was born in Puebla, worked with Nahuatl speakers, then wrote histories.

The first page of his Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos featured a woodcut of Santo Joseph with a dedication to him as guardian.

Joseph is mentioned as the husband of Mary in the Gospel of Matthew, which was the book that inspired Francis of Assisi to exchange earthly goods for poverty. Sometime around the year 145, the Gospel of James appeared. It described Joseph’s selection by the temple as the guardian of the adolescent Mary, in a tale reminiscent of Cinderella. All unmarried men of the House of David were ordered to bring their rods to the temple, where a sign from the Lord would identify the chosen man. It read:

"Joseph took his rod last; and, behold, a dove came out of the rod, and flew upon Joseph's head."

The book by Joseph’s son circulated in Greek manuscripts, but apparently not in Latin. In the early 600s the Gospel of Saint Matthew appeared in Latin, supposedly in a translation by Jerome. It elaborated on James.

"But as soon as he stretched forth his hand, and laid hold of his rod, immediately from the top of it came forth a dove whiter than snow, beautiful exceedingly, which, after long flying about the roofs of the temple, at length flew towards the heavens."

This gospel circulated widely. Brandon Hawke noted it moved into Anglo-Saxon tradition from the Carolingians in France. In 1260, an Italian Dominican, Jacobus de Voragine, included Saint Matthew’s story of Joseph in his Legenda Aurea. More than a thousand copies survive in manuscript. William Caxton published the Golden Legend in English in 1483. Alexander Wilkinson found a Castilian Flos Sanctorum published in the 1470s, a Catalan one from Barcelona in 1495, and Le Leyendo de los Santos from Burgos in 1499.

Voragine both simplified Matthew’s version, and embellished it:

"then Joseph by the commandment of the bishop brought forth his rod, and anon it flowered, and a dove descended from heaven thereupon."

The Council of Trent discouraged the interest in the legends of saints to promote factual biographies. Voragine’s text was republished in revisions by Alonso de Villegas in 1578 and by the Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneyra in 1599.

However, it’s the earlier image the Spanish shared with Caxton of the flowering rod that greeted the friars in Santa Cruz each time they opened the manual to read the baptismal language.

Notes: This James, better known as James the Just, was not the same disciple as James the Great, better known as Santiago. James the Just described Joseph as an elderly widow, which would have made himself the step-brother of Jesus.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez, The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Hawk, Brandon W. "Preaching the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew in Anglo-Saxon England," York Christian Apocrypha Symposium, 2015.

James. Gospel, translated by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Matthew. Gospel, translation by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Roberts, Alexander, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Ante-Nicene Fathers, volume 8, 1886; revised and edited by Kevin Knight.

Vetancurt, Agustín de. Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, first published 1674; woodcut from 1729 edition.

Voragine, Jacobus de. Legenda Aurea, translated by William Caxton, 1483; edited by F. S. Ellis, 1900.

Wikipedia. Primary source for history of the apocryphal gospels.

Wilkinson, Alexander S. Iberian Books, 2010.

Sunday, April 24, 2016

Franciscan Narratives

Franciscans produced two narrative genres. Both derived from their founding in 1209 as a monastic order dedicated to emulating Christ’s life of poverty and his last days of pain. As mentioned in the post for 10 April 2016, Isidro Félix de Espinosa wrote biographies of men associated with the missionary college in Querétaro that described their self-mortification rituals.

The second group of narratives arose from changing attitudes toward poverty. During the Black Death plague that arrived in Spain in 1348, Franciscan monasteries grew wealthy from "endowments for prayers for the dead, which were then usually founded with real estate."

In the stagnation that followed, the friars discipline was relaxed, and dissenters reformed into competing groups. In 1517, partly as a consequence of Bernardino Albizeschi’s sermons in Italy, Leo X selected one group as the true Franciscans, the Observant Friars Minors, and declared preaching their primary mission.

The Council of Trent reaffirmed their vows of poverty. However, by then many no longer understood that to mean they actually should live in poverty. Instead, they’d come to see their status as an opportunity for those with wealth, including monarchs, to insure their afterlives by supporting them with alms. Indeed, when Franciscans located their college at Querétaro, they selected that site over one closer to the missionary frontier "because of the hope that local alms would aid in supporting the college and its work, a hope which could not be realized in the sparse settlements of the north."

Unlike their contemporaries in New England, Franciscans had problems explaining why their expectations often were unfulfilled. Jonathan Edwards could point to "the meer Pleasure of God, I mean his sovereign Pleasure, his arbitrary Will, restrained by no Obligation" in Massachusetts in 1741, but Franciscans only had the kindly God who had sent them Christ.

Edwards could point to the "very Nature of carnal Men" where lay "corrupt Principles" that were "active and powerful, and exceeding violent in their Nature, and if it were not for the restraining Hand of God upon them, they would soon break out, they would flame out after the

same Manner as the same Corruptions, the same Enmity does in the Hearts of damned Souls, and would beget the same Torments in ‘em as they do in them." Administering the sacraments precluded accusing the wealthy and powerful of witchcraft or sin.

When others didn’t honor obligations they believed were due them, Franciscan writers could only resort to legal arguments that represented themselves as martyrs. The theme had been voiced in Perú in 1677 by Miguel Serrano de Alvarracín when he complained criollos were keeping Iberians from their rightful places in provinces that had been established generations before by Spaniards. "Is it just" he asked, "that we should be deprived of what we have planted and cultivated without even a mouthful being given to us?"

In Nuevo México, Observant Friars merged legends of martyrdom and sacrifice learned from oral tradition with legalities when they described their experiences. In 1760, Juan Sanz began his "account of lamentable happenings" in contemporary New Mexico with the Pueblo revolt. In his first paragraph, he wrote: "twenty-one religious perished at the hands of the Indians, some of them burned, others shot with arrows, while some were clubbed to death."

This had occurred almost sixty years before Sanz arrived at Zía in 1748. He could only have known some of those details from listening to others.

He arrived just after an El Niño, but experienced several dry stretches during his term. In 1760, he could still intone "this kingdom is as fertile in grain production as Old Castile. The wheat is unequaled; corn and all kinds of vegetables do well; fruits are few on account of the great amount of snow and ice; the meats, both of cattle and sheep, are most excellent. Besides the silver-bearing ores, which are well known, there is much copper, lead, antimony, and everything necessary for mining."

The consequences of drought and Comanche depredations could be seen everywhere in 1760, but the friar couldn’t credit them as the reason "all this lies waste, a kingdom with such great resources void of human energy." Instead, he argued it was all sacrificed "by the governors, for these gentlemen attend only to filling their own pockets."

His underlying assumptions of potential wealth were based on tales he’d heard from "many old men both in New Mexico and in the vicinity of Chihuahua." Their anecdotes probably reinforced stories he heard as a boy in the port of Cádiz that may have inspired him to migrate. It was probably only when such wealth didn’t come his way that he joined the Franciscans in Mexico City when he was 28.

One source for his effigy of New Mexico surely was Carlos Delgado, who’d been part of a council called in 1722 to explain to a representative of the viceroy why the area wasn’t more densely settled. In making a plea for increased funding, the group said "the country was rich in metals and well adapted to agriculture and the raising of stock, and that any expenditure of money by the government would be a good investment."

Sanz wasn’t with Delgado when the latter went to induce Moquis to abandon their pueblo for the Río Grande in 1745. But, he’d been told that, "because the said government had not assisted them with the necessary food, men and animals, they could not bring out more than two thousand souls." Most didn’t go beyond Zuñi.

He wasn’t with Delgado when the older friar first evangelized the Navajo, but in 1748 Sanz had been sent to continue Christianizing the ones at Cebolleta. When their efforts were supported by the governor, Sanz complained Joaquín Codallos ordered the pueblo of Ácoma to build a church at Cebolleta. He believed the demonstration of conscripted labor was what "created such a schism among the Apaches that the latter desisted from the intended conversion, and revolted."

The Franciscan concluded, "We were left disconsolate at such a fatal misfortune, which we were without power to remedy. This proves the hopelessness, unless God provides, of there being any more conversions."

They didn’t share the Puritan attitude that a failure to overcome adversity was a sign one lacked God’s grace, a sign to be disguised by renewed efforts. The Franciscan attitude that poverty was a condition that entitled them to support by the monarchy was absorbed by others. At that meeting in 1722 when Antonio Cobián Busto asked why there was so little to show from the viceroy’s earlier expenditures on the kingdom, men blamed their poverty, and their fear of Indian raids. As mentioned in the post for 21 February 2016, officials in 1746 again were invoking poverty as an entitlement, this time to evade paying taxes.

Notes: Black death was bubonic plague. Cobián’s visit was described in the post for 28 June 2015.

Alvarracín, Miguel Serrano de. Memorial, Madrid, 22 June 1677, quoted by Antonine Tibesar, "The Alternativa: A Study in Spanish-Creole Relations in Seventeenth-Century Peru," The Americas 11:229-283:1955.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889; quotations on council of 1722.

Bihl, Michael. "Order of Friars Minor," Charles George Herbermann, The Catholic Encyclopedia, volume 6, 1909; quotation on effects of Black Death.

Edwards, Jonathan. "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," sermon preached at Enfield, Connecticut, 8 July 1741; edited by Reiner Smolinski.

McCloskey, Michael B. The Formative Years of the Missionary College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro 1683-1733, 1955; quotation on alms and Querétaro

Norris, Jim. After "The Year Eighty," 2000; on Sanz’s background.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 November1760; translation in Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

The second group of narratives arose from changing attitudes toward poverty. During the Black Death plague that arrived in Spain in 1348, Franciscan monasteries grew wealthy from "endowments for prayers for the dead, which were then usually founded with real estate."

In the stagnation that followed, the friars discipline was relaxed, and dissenters reformed into competing groups. In 1517, partly as a consequence of Bernardino Albizeschi’s sermons in Italy, Leo X selected one group as the true Franciscans, the Observant Friars Minors, and declared preaching their primary mission.

The Council of Trent reaffirmed their vows of poverty. However, by then many no longer understood that to mean they actually should live in poverty. Instead, they’d come to see their status as an opportunity for those with wealth, including monarchs, to insure their afterlives by supporting them with alms. Indeed, when Franciscans located their college at Querétaro, they selected that site over one closer to the missionary frontier "because of the hope that local alms would aid in supporting the college and its work, a hope which could not be realized in the sparse settlements of the north."

Unlike their contemporaries in New England, Franciscans had problems explaining why their expectations often were unfulfilled. Jonathan Edwards could point to "the meer Pleasure of God, I mean his sovereign Pleasure, his arbitrary Will, restrained by no Obligation" in Massachusetts in 1741, but Franciscans only had the kindly God who had sent them Christ.

Edwards could point to the "very Nature of carnal Men" where lay "corrupt Principles" that were "active and powerful, and exceeding violent in their Nature, and if it were not for the restraining Hand of God upon them, they would soon break out, they would flame out after the

same Manner as the same Corruptions, the same Enmity does in the Hearts of damned Souls, and would beget the same Torments in ‘em as they do in them." Administering the sacraments precluded accusing the wealthy and powerful of witchcraft or sin.

When others didn’t honor obligations they believed were due them, Franciscan writers could only resort to legal arguments that represented themselves as martyrs. The theme had been voiced in Perú in 1677 by Miguel Serrano de Alvarracín when he complained criollos were keeping Iberians from their rightful places in provinces that had been established generations before by Spaniards. "Is it just" he asked, "that we should be deprived of what we have planted and cultivated without even a mouthful being given to us?"

In Nuevo México, Observant Friars merged legends of martyrdom and sacrifice learned from oral tradition with legalities when they described their experiences. In 1760, Juan Sanz began his "account of lamentable happenings" in contemporary New Mexico with the Pueblo revolt. In his first paragraph, he wrote: "twenty-one religious perished at the hands of the Indians, some of them burned, others shot with arrows, while some were clubbed to death."

This had occurred almost sixty years before Sanz arrived at Zía in 1748. He could only have known some of those details from listening to others.

He arrived just after an El Niño, but experienced several dry stretches during his term. In 1760, he could still intone "this kingdom is as fertile in grain production as Old Castile. The wheat is unequaled; corn and all kinds of vegetables do well; fruits are few on account of the great amount of snow and ice; the meats, both of cattle and sheep, are most excellent. Besides the silver-bearing ores, which are well known, there is much copper, lead, antimony, and everything necessary for mining."

The consequences of drought and Comanche depredations could be seen everywhere in 1760, but the friar couldn’t credit them as the reason "all this lies waste, a kingdom with such great resources void of human energy." Instead, he argued it was all sacrificed "by the governors, for these gentlemen attend only to filling their own pockets."

His underlying assumptions of potential wealth were based on tales he’d heard from "many old men both in New Mexico and in the vicinity of Chihuahua." Their anecdotes probably reinforced stories he heard as a boy in the port of Cádiz that may have inspired him to migrate. It was probably only when such wealth didn’t come his way that he joined the Franciscans in Mexico City when he was 28.

One source for his effigy of New Mexico surely was Carlos Delgado, who’d been part of a council called in 1722 to explain to a representative of the viceroy why the area wasn’t more densely settled. In making a plea for increased funding, the group said "the country was rich in metals and well adapted to agriculture and the raising of stock, and that any expenditure of money by the government would be a good investment."

Sanz wasn’t with Delgado when the latter went to induce Moquis to abandon their pueblo for the Río Grande in 1745. But, he’d been told that, "because the said government had not assisted them with the necessary food, men and animals, they could not bring out more than two thousand souls." Most didn’t go beyond Zuñi.

He wasn’t with Delgado when the older friar first evangelized the Navajo, but in 1748 Sanz had been sent to continue Christianizing the ones at Cebolleta. When their efforts were supported by the governor, Sanz complained Joaquín Codallos ordered the pueblo of Ácoma to build a church at Cebolleta. He believed the demonstration of conscripted labor was what "created such a schism among the Apaches that the latter desisted from the intended conversion, and revolted."

The Franciscan concluded, "We were left disconsolate at such a fatal misfortune, which we were without power to remedy. This proves the hopelessness, unless God provides, of there being any more conversions."

They didn’t share the Puritan attitude that a failure to overcome adversity was a sign one lacked God’s grace, a sign to be disguised by renewed efforts. The Franciscan attitude that poverty was a condition that entitled them to support by the monarchy was absorbed by others. At that meeting in 1722 when Antonio Cobián Busto asked why there was so little to show from the viceroy’s earlier expenditures on the kingdom, men blamed their poverty, and their fear of Indian raids. As mentioned in the post for 21 February 2016, officials in 1746 again were invoking poverty as an entitlement, this time to evade paying taxes.

Notes: Black death was bubonic plague. Cobián’s visit was described in the post for 28 June 2015.

Alvarracín, Miguel Serrano de. Memorial, Madrid, 22 June 1677, quoted by Antonine Tibesar, "The Alternativa: A Study in Spanish-Creole Relations in Seventeenth-Century Peru," The Americas 11:229-283:1955.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889; quotations on council of 1722.

Bihl, Michael. "Order of Friars Minor," Charles George Herbermann, The Catholic Encyclopedia, volume 6, 1909; quotation on effects of Black Death.

Edwards, Jonathan. "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," sermon preached at Enfield, Connecticut, 8 July 1741; edited by Reiner Smolinski.

McCloskey, Michael B. The Formative Years of the Missionary College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro 1683-1733, 1955; quotation on alms and Querétaro

Norris, Jim. After "The Year Eighty," 2000; on Sanz’s background.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 November1760; translation in Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

Franciscans and Society

Nueva México society was divided into four estates: Natives, Spanish-speakers, government employees, and the clergy. The first included those living in pueblos who still spoke one of several languages, nomadic groups like the Jicarilla and Navajo, and captives mainly from the plains. Spanish speakers were stratified by wealth, while the government was represented by short-term governors, longer-term appointees like alcaldes, and paid soldiers in the presidio.

Loyalties between groups were weak. Franciscans, like governors, were always outsiders who rarely heard the truth. Their relations with other groups were treacherous because none could be trusted. The appointees represented the local equivalent to the conflicts elsewhere between criollos and Spaniards.

Governors were expected to implement orders from the viceroy, while defending the kingdom’s boundaries. They knew there were rewards if they succeeded, and penalties if they didn’t. From at least the time of Diego de Vargas they wrote glowing, if misleading, chronicles of their deeds.

Viceroys learned to be suspicious, and instituted verification procedures. Each new governor was expected to canvass each of the towns and pueblos to learn if there were unreported problems from the previous administration. Of course, they never found any.

It isn’t clear if men with land or those in the pueblos were willing to make public complaints. The governor only stayed a few years, but each new man might regard anyone who criticized his predecessor with suspicion.

A bigger concern may have been members of governors’ administrations who would have been implicated in complaints. Soldiers in the presidio and alcaldes stayed in their communities. Angélico Chávez said, the Franciscan custos didn’t critize the secular clergyman, Santiago Roybal, "for fear that Roybal would avail himself of an excuse to set the military on the Religious."

The alcaldes were described by Franciscan Carlos Delgado as men who took the positions "solely for the purpose of advancing their own interests and acquiring property with which to make presents to the governors." Another friar, Juan Sanz, noted appointments went to those "who gives the most mules or sheep."

Pedro de Rivera probably was responsible for the regression of alcaldeships into the sinecures purchased in hopes of profit that were common in Nuevo España. In 1726, he had curtailed appointing men who were enlisted in the presidio because he believed alcalde mayores "had the privilege of retirement and who received a fixed salary from the king." Whoever held the position still had the same responsibilities, but suddenly had less income.

Franciscans found the pueblos equally unreliable. They had accepted missionaries under threat of force by Diego de Vargas, and used every tool available to them to keep both them and the alcaldes as distant as possible.

When the bishop of Durango talked to them in 1730, they told Benito Crespo what they thought he wanted to hear. They intimated the only reason they didn’t confess at least once a year was they had to use interpreters, and would do so more often if the fathers spoke their language. One suspects the real reason they didn’t confess was that it violated some basic norm. Language was simply a useful subterfuge.

After Juan Antonio de Ornedal made the same indictment in 1750, Delgado observed the Natives "know how to lament and complain in a language, or idiom, in which their laments may be understood and comprehended" and yet they are supposed to be "mute in Castilian."

Simultaneously, pueblo representatives were telling friars the reasons they didn’t covert was because of bad things the governor and his representatives had done to them. Then, they told the alcaldes negative things about the friars.

It may well be the reason the friars were transferred so often, especially if they began to understand the local language, was some comment made to the authorities to have them removed before they could be effective. The men who stayed the longest at San Juan and Santa Clara, Juan de la Cruz and Manuel Sopeña, were ones mentioned by Crespo as among the most negligent.

Reports from the colonists were equally suspect. They wanted the presidio to protect them, but didn’t like paying taxes or going on campaigns. Philip V and his viceroys wanted tax and tithe collection to be more efficient. Sanz believed that, since governors had become responsible for collecting the tithe, "the country has been even worse off. Formerly the settlers exerted themselves to sow because the governor bought everything from them in order to supply the presidio, but now it taxes them to be able to sow enough for their own sustenance."

At the same time, the settlers wanted the friars to pacify the pueblos they didn’t want them interfering in their own affairs, any more than was necessary to legitimatize marriages. Crespo indicated that, when he suggested the churches in Albuquerque, Santa Fé and Santa Cruz could be transferred to his jurisdiction, he was told "the citizens desire this with all eagerness, and they asked me to seek it."

Notes: Crespo comments on Juan de la Cruz and Manuel Sopeña were described in the post for 28 June 2015. Rivera’s directive on alcaldes was discussed in the post for 3 January 2016. Friar transfers between missions were discussed in the post for 6 April 2016. The post for 27 March 2016 discussed Benito Crespo’s proposed mission transfers.

Adams, Eleanor B. Bishop Tamarón’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760, 1954.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Chávez, Angélico. "El Vicario Don Santiago Roybal," El Palacio 65:231-252:1948.

Crespo y Monroy, Benito. Letter to the viceroy, Juan Vásquez de Acuña, 8 September 1730; translation in Adams; recommended secularizing villa missions.

_____. Letter to the viceroy, Juan Vásquez de Acuña, 25 September 1730; translation in Adams; discussed reasons for not confessing.

Delgado, Carlos. Report to our Reverend Father Ximeno concerning the abominable hostilities and tyrannies of the governors and alcaldes mayores toward the Indians, to the consternation of the custodia, 1750; translation in Bandelier.

Delgado [Esp Hist I17 p427] alcades; p439 - language

Rivera Villalón, Pedro de. Proyecto (inspection report), 1728, in Thomas H. Naylor and Charles W. Polzer. Pedro de Rivera and the Military Regulations for Northern New Spain, 1724-1729, 1988.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 Novwmber1760; translation in Bandelier.

Loyalties between groups were weak. Franciscans, like governors, were always outsiders who rarely heard the truth. Their relations with other groups were treacherous because none could be trusted. The appointees represented the local equivalent to the conflicts elsewhere between criollos and Spaniards.

Governors were expected to implement orders from the viceroy, while defending the kingdom’s boundaries. They knew there were rewards if they succeeded, and penalties if they didn’t. From at least the time of Diego de Vargas they wrote glowing, if misleading, chronicles of their deeds.

Viceroys learned to be suspicious, and instituted verification procedures. Each new governor was expected to canvass each of the towns and pueblos to learn if there were unreported problems from the previous administration. Of course, they never found any.

It isn’t clear if men with land or those in the pueblos were willing to make public complaints. The governor only stayed a few years, but each new man might regard anyone who criticized his predecessor with suspicion.

A bigger concern may have been members of governors’ administrations who would have been implicated in complaints. Soldiers in the presidio and alcaldes stayed in their communities. Angélico Chávez said, the Franciscan custos didn’t critize the secular clergyman, Santiago Roybal, "for fear that Roybal would avail himself of an excuse to set the military on the Religious."

The alcaldes were described by Franciscan Carlos Delgado as men who took the positions "solely for the purpose of advancing their own interests and acquiring property with which to make presents to the governors." Another friar, Juan Sanz, noted appointments went to those "who gives the most mules or sheep."

Pedro de Rivera probably was responsible for the regression of alcaldeships into the sinecures purchased in hopes of profit that were common in Nuevo España. In 1726, he had curtailed appointing men who were enlisted in the presidio because he believed alcalde mayores "had the privilege of retirement and who received a fixed salary from the king." Whoever held the position still had the same responsibilities, but suddenly had less income.

Franciscans found the pueblos equally unreliable. They had accepted missionaries under threat of force by Diego de Vargas, and used every tool available to them to keep both them and the alcaldes as distant as possible.

When the bishop of Durango talked to them in 1730, they told Benito Crespo what they thought he wanted to hear. They intimated the only reason they didn’t confess at least once a year was they had to use interpreters, and would do so more often if the fathers spoke their language. One suspects the real reason they didn’t confess was that it violated some basic norm. Language was simply a useful subterfuge.

After Juan Antonio de Ornedal made the same indictment in 1750, Delgado observed the Natives "know how to lament and complain in a language, or idiom, in which their laments may be understood and comprehended" and yet they are supposed to be "mute in Castilian."

Simultaneously, pueblo representatives were telling friars the reasons they didn’t covert was because of bad things the governor and his representatives had done to them. Then, they told the alcaldes negative things about the friars.

It may well be the reason the friars were transferred so often, especially if they began to understand the local language, was some comment made to the authorities to have them removed before they could be effective. The men who stayed the longest at San Juan and Santa Clara, Juan de la Cruz and Manuel Sopeña, were ones mentioned by Crespo as among the most negligent.

Reports from the colonists were equally suspect. They wanted the presidio to protect them, but didn’t like paying taxes or going on campaigns. Philip V and his viceroys wanted tax and tithe collection to be more efficient. Sanz believed that, since governors had become responsible for collecting the tithe, "the country has been even worse off. Formerly the settlers exerted themselves to sow because the governor bought everything from them in order to supply the presidio, but now it taxes them to be able to sow enough for their own sustenance."

At the same time, the settlers wanted the friars to pacify the pueblos they didn’t want them interfering in their own affairs, any more than was necessary to legitimatize marriages. Crespo indicated that, when he suggested the churches in Albuquerque, Santa Fé and Santa Cruz could be transferred to his jurisdiction, he was told "the citizens desire this with all eagerness, and they asked me to seek it."

Notes: Crespo comments on Juan de la Cruz and Manuel Sopeña were described in the post for 28 June 2015. Rivera’s directive on alcaldes was discussed in the post for 3 January 2016. Friar transfers between missions were discussed in the post for 6 April 2016. The post for 27 March 2016 discussed Benito Crespo’s proposed mission transfers.

Adams, Eleanor B. Bishop Tamarón’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760, 1954.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Chávez, Angélico. "El Vicario Don Santiago Roybal," El Palacio 65:231-252:1948.

Crespo y Monroy, Benito. Letter to the viceroy, Juan Vásquez de Acuña, 8 September 1730; translation in Adams; recommended secularizing villa missions.

_____. Letter to the viceroy, Juan Vásquez de Acuña, 25 September 1730; translation in Adams; discussed reasons for not confessing.

Delgado, Carlos. Report to our Reverend Father Ximeno concerning the abominable hostilities and tyrannies of the governors and alcaldes mayores toward the Indians, to the consternation of the custodia, 1750; translation in Bandelier.

Delgado [Esp Hist I17 p427] alcades; p439 - language

Rivera Villalón, Pedro de. Proyecto (inspection report), 1728, in Thomas H. Naylor and Charles W. Polzer. Pedro de Rivera and the Military Regulations for Northern New Spain, 1724-1729, 1988.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 Novwmber1760; translation in Bandelier.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

Revivals

Religious fervor has a tendency to abate with time. By 1740, many Puritans in New England had grown so comfortable with their faith they do longer wondered if they were among the elect. It had become the corollary of their financial success.

Then, George Whitefield came from England to preach outdoors without patronage from any particular clergyman or church. While his theology was Calvinist, his style was drawn from theater. The audience didn’t hear about a fearsome God, it experienced salvation. What we now call the First Great Awakening spread through Pennsylvania, New York and New England.

In Nueva España another form of inertia had set in. Even under the constrictions of drought and war, life was comfortable. As David Brading mentioned in the post for 30 March 2016, no one protested when parishes administered by religious orders were turned over to secular clergy in 1749.

Isidro Félix de Espinosa had little interest in chronicling Franciscan activities when asked by the order in Michoacán to write its history. Instead, the Querétaro native suggested, more was happening in the missionary colleges where Franciscans were training men to convert the pagans in Tejas. The challenges of new conquests were invigorating the faith of men.

In 1737, he published a biography of one man he knew from his years in Tejas. Antonio Margil de Jesús never looked anyone in the face lest he be tempted by the devil. He scourged himself daily, wore cilices three times a week, and every night went walking with a heavy cross.

A few years later Espinosa wrote a history of the Querétaro college where he had served as guardian. One of the men he identified as a model for young friars went into the fields barefoot every Friday. Melchoir López de Jesús carried "a heavy cross on his shoulders, a cord at his neck, and a crown of thorns pressed so tight that at times drops of blood drawn from the thorns could be seen on his venerable face."

Later, he wrote his own brother, Juan Antonio Pérez de Espinosa, slept on leather sheets, fasted regularly, wore cilices, scourged himself three times a week, and slept in a coffin. He kept a copy of his family tree decorated with skulls and skeletons.

Espinosa said nothing of his own habits, but did say when Margil and López were in Guatemala, they were so appalled by the prevailing idolatry they made the Indians repent by walking in public processions carrying crosses and wearing cilices.

While the two revivals occurred at roughly the same time, they differed in their consequences. The Great Awakening introduced a new style and new organization to reach a new audience, the artisans and yeomen who lived outside the Puritan, Quaker, and Anglican elites.

The Franciscan activities that attracted David Brading’s interest harkened back to medieval practice, perhaps done in the face of competition from Jesuits. Both were lobbying for rights to evangelize the Moqui when he was writing.

When the Jesuits were given the Moqui commission, Carlos Delgado and Ignacio del Pino went to the Moqui towns in 1743 and induced 144 Tiwa speakers to return. Then they demanded the governor, Gaspar de Mendoza, provide them with a pueblo. He refused to act without the viceroy’s authorization. Most of the returnees were sent to Jémez, the rest to Isleta.

Delgado was one of the men sent from Andalucía to the Querétaro college, but Jim Norris found he "left that group for unspecified reasons." No one I’ve read has said if he followed the self-mortification regimes of his college’s founders, but he did absorb their methods for conducting mass campaigns.

The next year, the head of the Franciscans in México recommended local friars direct their attention to the Navajo, who had been identified by Benito Crespo as potential Christians in 1730. Delgado and José de Irigoyen headed back west, distributed gifts, and claimed 4,000 souls.

The impressed viceroy authorized four missions with a garrison for the latter. The new governor, Joaquín Codallos, agreed to send an escort when Delgado, Irigoyen, and Pino returned west in 1745.

Juan Miguel Menchero followed them in 1746. He convinced 500 or 600 Athabascan speakers to move down to Cebolleta in the Ácoma region. However, when he returned two years later, the drought was so severe the springs had dried. The Navajo had been pushed south by the Utes who lived in an even more arid region. They could see the problems with sedentary agriculture.

In 1750, they told the priest assigned to Cebolleta, "they did not want pueblos now." They said, they were willing "to have water thrown upon" the heads of some of their children but they could not "stay in one place because they had been raised like deer." They thought maybe the ones who were baptized "might perhaps build a pueblo and have a father" someday.

In the meantime, Menchero did succeed in getting permission to resettle the Moqui émigrés at Sandía in 1748, satisfied he had planted "the seed of the Christian Faith among the residents of the pueblos of Ácoma, Laguna and Zía."

Notes: Cilices were what we commonly call hair shirts, although the rough cloths could be worn on the chest or around the loin. I don’t know if self-mortification was a dominant theme in the works of Espinosa, or was of particular interest to Brading. It may have been a matter of etiquette that individuals didn’t mention their own practices.

Brading, D. A. Church and State in Bourbon Mexico, 1994.

Espinosa, Isidro Félix de. Crónica Apostólica, 1746; cited by Brading on López.

_____. Crónica de la Provincia Franciscan, 1749 manuscript; cited by Brading on Franciscans in Michoacán.

_____. El familiar de la América, 1753 manuscript; cited by Brading on Juan Antonio Pérez de Espinosa

_____. El Peregrino, 1737; cited by Brading on Margil.

Menchero, Juan Miguel. Petition to Joaquín Codallos y Rabal, 5 April 1748; translation in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico, volume 2, 1914.

Norris, Jim. After "The Year Eighty," 2000.

Reeve, Frank D. "The Navaho-Spanish Peace: 1720's-1770's," New Mexico Historical Review 34:9-40:1959.

Ruyamor, Fernando. Testimony as alcalde mayor of Ácoma and Laguna before Bernardo Antonio de Bustamante y Tagle at Ácoma, 18 April 1750, translation in Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett; quotation on free as deer.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 November1760; translation in Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Then, George Whitefield came from England to preach outdoors without patronage from any particular clergyman or church. While his theology was Calvinist, his style was drawn from theater. The audience didn’t hear about a fearsome God, it experienced salvation. What we now call the First Great Awakening spread through Pennsylvania, New York and New England.

In Nueva España another form of inertia had set in. Even under the constrictions of drought and war, life was comfortable. As David Brading mentioned in the post for 30 March 2016, no one protested when parishes administered by religious orders were turned over to secular clergy in 1749.

Isidro Félix de Espinosa had little interest in chronicling Franciscan activities when asked by the order in Michoacán to write its history. Instead, the Querétaro native suggested, more was happening in the missionary colleges where Franciscans were training men to convert the pagans in Tejas. The challenges of new conquests were invigorating the faith of men.

In 1737, he published a biography of one man he knew from his years in Tejas. Antonio Margil de Jesús never looked anyone in the face lest he be tempted by the devil. He scourged himself daily, wore cilices three times a week, and every night went walking with a heavy cross.

A few years later Espinosa wrote a history of the Querétaro college where he had served as guardian. One of the men he identified as a model for young friars went into the fields barefoot every Friday. Melchoir López de Jesús carried "a heavy cross on his shoulders, a cord at his neck, and a crown of thorns pressed so tight that at times drops of blood drawn from the thorns could be seen on his venerable face."

Later, he wrote his own brother, Juan Antonio Pérez de Espinosa, slept on leather sheets, fasted regularly, wore cilices, scourged himself three times a week, and slept in a coffin. He kept a copy of his family tree decorated with skulls and skeletons.

Espinosa said nothing of his own habits, but did say when Margil and López were in Guatemala, they were so appalled by the prevailing idolatry they made the Indians repent by walking in public processions carrying crosses and wearing cilices.

While the two revivals occurred at roughly the same time, they differed in their consequences. The Great Awakening introduced a new style and new organization to reach a new audience, the artisans and yeomen who lived outside the Puritan, Quaker, and Anglican elites.

The Franciscan activities that attracted David Brading’s interest harkened back to medieval practice, perhaps done in the face of competition from Jesuits. Both were lobbying for rights to evangelize the Moqui when he was writing.

When the Jesuits were given the Moqui commission, Carlos Delgado and Ignacio del Pino went to the Moqui towns in 1743 and induced 144 Tiwa speakers to return. Then they demanded the governor, Gaspar de Mendoza, provide them with a pueblo. He refused to act without the viceroy’s authorization. Most of the returnees were sent to Jémez, the rest to Isleta.

Delgado was one of the men sent from Andalucía to the Querétaro college, but Jim Norris found he "left that group for unspecified reasons." No one I’ve read has said if he followed the self-mortification regimes of his college’s founders, but he did absorb their methods for conducting mass campaigns.

The next year, the head of the Franciscans in México recommended local friars direct their attention to the Navajo, who had been identified by Benito Crespo as potential Christians in 1730. Delgado and José de Irigoyen headed back west, distributed gifts, and claimed 4,000 souls.

The impressed viceroy authorized four missions with a garrison for the latter. The new governor, Joaquín Codallos, agreed to send an escort when Delgado, Irigoyen, and Pino returned west in 1745.

Juan Miguel Menchero followed them in 1746. He convinced 500 or 600 Athabascan speakers to move down to Cebolleta in the Ácoma region. However, when he returned two years later, the drought was so severe the springs had dried. The Navajo had been pushed south by the Utes who lived in an even more arid region. They could see the problems with sedentary agriculture.

In 1750, they told the priest assigned to Cebolleta, "they did not want pueblos now." They said, they were willing "to have water thrown upon" the heads of some of their children but they could not "stay in one place because they had been raised like deer." They thought maybe the ones who were baptized "might perhaps build a pueblo and have a father" someday.

In the meantime, Menchero did succeed in getting permission to resettle the Moqui émigrés at Sandía in 1748, satisfied he had planted "the seed of the Christian Faith among the residents of the pueblos of Ácoma, Laguna and Zía."

Notes: Cilices were what we commonly call hair shirts, although the rough cloths could be worn on the chest or around the loin. I don’t know if self-mortification was a dominant theme in the works of Espinosa, or was of particular interest to Brading. It may have been a matter of etiquette that individuals didn’t mention their own practices.

Brading, D. A. Church and State in Bourbon Mexico, 1994.

Espinosa, Isidro Félix de. Crónica Apostólica, 1746; cited by Brading on López.

_____. Crónica de la Provincia Franciscan, 1749 manuscript; cited by Brading on Franciscans in Michoacán.

_____. El familiar de la América, 1753 manuscript; cited by Brading on Juan Antonio Pérez de Espinosa

_____. El Peregrino, 1737; cited by Brading on Margil.

Menchero, Juan Miguel. Petition to Joaquín Codallos y Rabal, 5 April 1748; translation in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico, volume 2, 1914.

Norris, Jim. After "The Year Eighty," 2000.

Reeve, Frank D. "The Navaho-Spanish Peace: 1720's-1770's," New Mexico Historical Review 34:9-40:1959.

Ruyamor, Fernando. Testimony as alcalde mayor of Ácoma and Laguna before Bernardo Antonio de Bustamante y Tagle at Ácoma, 18 April 1750, translation in Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett; quotation on free as deer.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 November1760; translation in Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Labels:

07 México 6-10,

07 Santa Cruz 16-20,

30 New England

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)