Four traditions influenced religious beliefs in Santa Cruz.

Leonor Domínguez married into a family whose faith was a compound of Puebla and Hapsburg beliefs. It was a dangerous world ruled by the devil who worked through witches. As mentioned in posts for 30 March and 6 April 2014, Juan Griego’s wife, Pascuala Bernal, was a Nahuatl speaker probably from the Puebla-Veracruz area who brought herbal traditions with her. Her son married the daughter of Beatriz de los Ángeles, a Mexican native accused of sorcery.

Roque de Madrid may have been the grandson of another Mexican native, Francisca Jiménez, but his beliefs came from his grandfather, Francisco de Madrid, who was a capitán and member of the Santa Fé cabildo before the Revolt. Roque’s older brother, Lorenzo, used to call himself "the oldest Conquistador" in the colony.

Madrid evoked the Asturian legend that the disciple James aided Ramiro I in the battle of Clavijo against the Emir of Córdoba in 834. He named one place "with excellent grazing and many cienegas and springs" the Valle de Santiago. When they entered battle with the Navajo, he invoked "the name of our lord Santiago."

Instead of witches, Madrid fought infidels. He used the word entrada to describe his 1705 campaign against the unchristianized Navajo and named his first camp site in the Sierra Florida for Nuestra Señora de Covadonga. She had blessed the first battle of Spain’s Reconquest in 722. When his horse stumbled and he fell down a slope, he said "only by a miracle from La Conquistadora did I escape with my life."

His Lord was the miracle worker of the gospels. Madrid gave thanks whenever he found good pasturage or decent passage. One time he said: "God saw fit that after a little more than one-fourth of a league, I came out to a country that was somewhat easier of passage." Another time, he told his troops he had located water. "They all rejoiced and gave thanks to God."

After they crossed the Continental Divide into the arid lands south of the Navajo River, their horses were "staggering and dizzy from thirst." Madrid recorded:

"Thus, it was that our horses went among the rocks sniffing and neighing in such a way that it seemed that they understood and were asking God for water with their cries. In the midst of this affliction, our chaplain began to clamor to heaven, asking for relief; all my companions and I joined him. Our exclamations reached Heaven, and suddenly a small cloud arose giving a little rain, but it was not enough to wet our cloaks."

Instead, the small cloud dropped its load upstream. A dry arroyo turned into "a great flood" where they watered the animals. Madrid said:

"We praised God, thanking him for this miracle. Then He sent rain in such abundance that all the fields turned into lagunas. In the hour and a half that the rain lasted, the water gave us no place to halt."

The priest, Augustín de Colina, preached a sermon on the Saturday before their first assault on the Navajo. Madrid said the Franciscan reminded the men they must treat the enemy justly, and to do so they needed "to be in God’s grace." He spent the day listening to confessions "from all those who wanted to prepare themselves and enter into battle in a state of grace." The following day he celebrated the "Holy Sacrifice of the Mass."

The concern with grace probably came from the same Biblical source as Jean Calvin’s. In both cases, individuals had to prove to their neighbors they were in such a state. In New England, if they succeeded, they were accepted as members of the church and given privileges accorded the elite. In Nuevo México, they became Españoles, even if their heritage was mixed or unknown. The difference is Calvin limited the elect to those predestined from birth to be saved by God, while the friars bestowed grace through the administration of the sacraments.

Madrid’s Lord was not the Jehovah of the Puritans. He said, when they again were lacking adequate water, "I left again, trusting in God and His Most Holy Mother that they would succor me in this time of need." He named one lake Laguna de San Joseph for Christ’s guardian.

Notes:

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Rick Hendricks and John P. Wilson, The Navajos in 1705, 1996.

Chávez, Angélico. Origins of New Mexico Families, 1992 revised edition.

Showing posts with label 01 Madrid. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 01 Madrid. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 02, 2015

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Santa Cruz Militia

Two military ranks appeared in diligencias matrimoniales: capitánes of the militia and soldiers in the presidio. The latter included sargentos and sargento mayors. Other ranks existed in Santa Fé, but these were the ones known in Santa Cruz.

Thomas Naylor said New Spain paid its soldiers so poorly, few would enlist. Only the worst were turned away. In 1708, charges were brought against Martín García and six men under his command for mistreating men at Galisteo. Cristóbal Lucero stabbed one in the head. Miguel Durán threw others off scaffolds. García himself ordered Lorenzo Rodríguez to tie, hang, and whip a man.

There was no death penalty for Lucero killing a man. The Duque de Albuquerque wanted him sentenced to a distant presidio and the others warned. The viceroy was overruled by his auditor generals of war. In 1710, they suggested García also be sentenced to another presidio and Durán be warned. One of the pardoned, Alonso Garcia de Noriega, was the nephew of Leonor Domínguez and Alonso Rael de Aguilar. Their uncle Lázaro had been killed at Galisteo in 1680.

Low wages meant few soldiers could afford families. With no patrimony, their sons enlisted and their daughters had few prospects. The only man who married in Santa Cruz in these years was a second generation soldier. Miguel Tenorio de Alba had risen to capitán by the time he wed Agustína Romero in 1705. She was the daughter of Salvador Romero and María López de Ocanto.

The only military men called to witness Santa Cruz weddings were Sargento Ambrosio Fresqui in 1703 and Alonso Fernandéz in 1701. The one was likely the son or grandson of Capitán Juan Fresqui. The other had come from Sombrerete with his father. Capitán Juan Fernandéz de la Pedrera had migrated from Galicia.

A division without a name existed between militia capitáns and their men. Francisco Cuervo reviewed the troops in Santa Cruz in April of 1705. Eight-three men showed, but only twenty-three had horses or mules. Twenty-two had no weapons. It’s not known if two-thirds of the men had had animals they sold, if the animals they had been issued when the villa was settled had grown old, or if they never had had horses or mules.

When Roque de Madrid pursued the Navajo in August of that year, all the men were mounted and had spare animals. Cuervo had brought 600 horses from Nuevo Vizcaya. There were more than 700 horses in Madrid’s campaign herd, including those of the "Indian allies."

When Madrid started across the highlands west of the Tusas, he sent "war captains from the Tewa and Picurís nations" ahead to suggest a route. When they returned, "they laid before me as many difficulties and inconveniences as they possibly could." He ignored them to "follow the slope and the breaks of the mountains by a route no Spaniard or person from any other nation had taken until now," but did take the precaution of doubling the squadron for the horses.

A few days later, he sent his scouts ahead again, and "they returned to me and raised even greater objections to my entrada." Madrid "paid them no heed, because my mind was made up to continue until I saw everything to its conclusion."

Juan de Ulibarrí was sent across the prairies to El Cuartelejo in 1706. They met other Apache who warned them of dangerous bands ahead. He thanked them for their advice, "but I was trusting in our God who was the creator of everything and who was to keep us free from the present dangers."

Later, after they had crossed the Arkansas river, Ulibarrí’s pueblo guides warned him, "we would undergo much suffering because there was no water." The men got lost following hummocks of grass left as a trail by the Apache, but two scouts did find water. The next day, they got lost again. This time "I, with the experience of the preceding day, scattered the whole command" and so found a dry arroyo with a spring.

After they had fought several successful battles with the Navajo, Madrid called a council of "active officials, military leaders, and reserves." The horses were suffering, the men were sick from eating green corn. He asked what was "appropriate" for "a soldier’s honor."

They answered, the enemy would now hide from fear of their weapons, and so little would be gained from pursuing them. They felt it was time to "withdraw our forces to the royal presidio."

When Ulibarrí needed to violate colonial policy against arming natives by providing them with a gun in exchange for one they had taken from the Pawnee, he called a meeting of his advisors. "We had agreed by common consent that it was better to hand it over to them so that in no way should they lack confidence in our word."

There was one other division within the military, the one between men like Madrid and Ulibarrí and the men they commanded. When he was determining the best strategy for dealing with the Navajo, Madrid said he feared "the treachery of these barbarians because of my many years of experience fighting them."

But it was more than experience. It took judgement, intuition and an ability to learn from the unexpected to chart paths through unexplored wilderness, intelligence to devise ruses to trick the Navajo, and wisdom to listen to the tenor of what men said.

Such military virtues were universally recognized. Jacques Marquette said of his commander, Louis Joliet: "He possesses Tact and prudence, which are the chief qualities necessary for the success of a voyage as dangerous as it is difficult. Finally, he has the Courage to dread nothing where everything is to be Feared."

Notes: The roster doesn’t exist from Madrid’s campaign, so it’s impossible to know how many horses were available to each man.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks; Madrid quotations.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; on Cuervo.

Naylor, Thomas H., Diana Hadley, and Mardith K. Schuetz-Miller. The Presidio and Militia on the Northern Frontier of New Spain, volume 2, part 2, 1997; on trial of Martín García. The records they transcribed didn’t name all six men.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Thomas Naylor said New Spain paid its soldiers so poorly, few would enlist. Only the worst were turned away. In 1708, charges were brought against Martín García and six men under his command for mistreating men at Galisteo. Cristóbal Lucero stabbed one in the head. Miguel Durán threw others off scaffolds. García himself ordered Lorenzo Rodríguez to tie, hang, and whip a man.

There was no death penalty for Lucero killing a man. The Duque de Albuquerque wanted him sentenced to a distant presidio and the others warned. The viceroy was overruled by his auditor generals of war. In 1710, they suggested García also be sentenced to another presidio and Durán be warned. One of the pardoned, Alonso Garcia de Noriega, was the nephew of Leonor Domínguez and Alonso Rael de Aguilar. Their uncle Lázaro had been killed at Galisteo in 1680.

Low wages meant few soldiers could afford families. With no patrimony, their sons enlisted and their daughters had few prospects. The only man who married in Santa Cruz in these years was a second generation soldier. Miguel Tenorio de Alba had risen to capitán by the time he wed Agustína Romero in 1705. She was the daughter of Salvador Romero and María López de Ocanto.

The only military men called to witness Santa Cruz weddings were Sargento Ambrosio Fresqui in 1703 and Alonso Fernandéz in 1701. The one was likely the son or grandson of Capitán Juan Fresqui. The other had come from Sombrerete with his father. Capitán Juan Fernandéz de la Pedrera had migrated from Galicia.

A division without a name existed between militia capitáns and their men. Francisco Cuervo reviewed the troops in Santa Cruz in April of 1705. Eight-three men showed, but only twenty-three had horses or mules. Twenty-two had no weapons. It’s not known if two-thirds of the men had had animals they sold, if the animals they had been issued when the villa was settled had grown old, or if they never had had horses or mules.

When Roque de Madrid pursued the Navajo in August of that year, all the men were mounted and had spare animals. Cuervo had brought 600 horses from Nuevo Vizcaya. There were more than 700 horses in Madrid’s campaign herd, including those of the "Indian allies."

When Madrid started across the highlands west of the Tusas, he sent "war captains from the Tewa and Picurís nations" ahead to suggest a route. When they returned, "they laid before me as many difficulties and inconveniences as they possibly could." He ignored them to "follow the slope and the breaks of the mountains by a route no Spaniard or person from any other nation had taken until now," but did take the precaution of doubling the squadron for the horses.

A few days later, he sent his scouts ahead again, and "they returned to me and raised even greater objections to my entrada." Madrid "paid them no heed, because my mind was made up to continue until I saw everything to its conclusion."

Juan de Ulibarrí was sent across the prairies to El Cuartelejo in 1706. They met other Apache who warned them of dangerous bands ahead. He thanked them for their advice, "but I was trusting in our God who was the creator of everything and who was to keep us free from the present dangers."

Later, after they had crossed the Arkansas river, Ulibarrí’s pueblo guides warned him, "we would undergo much suffering because there was no water." The men got lost following hummocks of grass left as a trail by the Apache, but two scouts did find water. The next day, they got lost again. This time "I, with the experience of the preceding day, scattered the whole command" and so found a dry arroyo with a spring.

After they had fought several successful battles with the Navajo, Madrid called a council of "active officials, military leaders, and reserves." The horses were suffering, the men were sick from eating green corn. He asked what was "appropriate" for "a soldier’s honor."

They answered, the enemy would now hide from fear of their weapons, and so little would be gained from pursuing them. They felt it was time to "withdraw our forces to the royal presidio."

When Ulibarrí needed to violate colonial policy against arming natives by providing them with a gun in exchange for one they had taken from the Pawnee, he called a meeting of his advisors. "We had agreed by common consent that it was better to hand it over to them so that in no way should they lack confidence in our word."

There was one other division within the military, the one between men like Madrid and Ulibarrí and the men they commanded. When he was determining the best strategy for dealing with the Navajo, Madrid said he feared "the treachery of these barbarians because of my many years of experience fighting them."

But it was more than experience. It took judgement, intuition and an ability to learn from the unexpected to chart paths through unexplored wilderness, intelligence to devise ruses to trick the Navajo, and wisdom to listen to the tenor of what men said.

Such military virtues were universally recognized. Jacques Marquette said of his commander, Louis Joliet: "He possesses Tact and prudence, which are the chief qualities necessary for the success of a voyage as dangerous as it is difficult. Finally, he has the Courage to dread nothing where everything is to be Feared."

Notes: The roster doesn’t exist from Madrid’s campaign, so it’s impossible to know how many horses were available to each man.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks; Madrid quotations.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; on Cuervo.

Naylor, Thomas H., Diana Hadley, and Mardith K. Schuetz-Miller. The Presidio and Militia on the Northern Frontier of New Spain, volume 2, part 2, 1997; on trial of Martín García. The records they transcribed didn’t name all six men.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Labels:

01 Domínguez,

01 Madrid,

01 Ulibarrí,

09 Santa Cruz 11-15

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Navajo Raids

Diego de Vargas left Nuevo México believing local indios bárbaros fell into two groups: Athabaskan speakers and Shoshone speakers. Navajo and Apache were grouped together in the first, Ute and Comanche in the second.

When he returned in 1703, differences between bands were becoming clear. Navajo attacked from the north and west. Faraón Apache came from the east.

In 1704, de Vargas led a force against the Faraón in the Sandías that mustered in Bernalillo. The war captain from Santa Clara, Juan Roque, was there with four men. Lorenzo brought five men from San Juan.

By the time Francisco Cuervo arrived to replace de Vargas in 1705, the Navajo had become more dangerous. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso twice. He immediately stationed presidio troops at the most exposed points, including Santa Clara on the west side of the Río Grande.

In March, Roque de Madrid pursued them with 65 men. They included soldiers from the presidio, the men assigned to Santa Clara, and the militia. In August, Cuervo sent him north from San Juan to follow the Navajo into their homeland. He went through uncharted territory north of Taos and west of the Continental Divide. When he returned he remarked, "we could make war on them again with greater advantage than at present, because all the men are now experienced in this land, the ways in and out, and we would return with more food."

The Navajo had made peace with Cuervo, not with the entity called Nuevo México. José Chacón took over as governor in 1707 during a severe drought. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso in 1708. Madrid was dispatched with presidio forces, settlers from Santa Cruz, and auxiliaries from the three affected pueblos.

Navajo raids continued. They stole animals from Santa Clara in 1709. Chacón sent troops to no avail, and so did his successor, Juan Flores Mogollón. Soldiers now knew about the upper reaches of the Chama river and followed it directly. Madrid attacked again in March of 1714, and killed 30 Navajo. Raids stopped. Flores took away the pueblos’ guns in July.

Notes:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s 1705 campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; it gives no details on the men who mustered, refers to the local auxiliaries as Tewa, and lists a few men who were his staff. Only Naranjo was from Santa Cruz.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Vargas, Diego de. War edicts, 27 March-2 April, 1704, in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

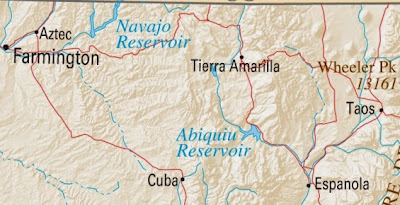

Map: United States Department of the Interior. Geological Survey. National Atlas of the United States of America. "New Mexico," 2004.

Hendricks and Wilson reconstructed Madrid’s 1705 route up the red line at the right (Route 68) to the first river (blue line). From there (Pilar) they went west to the next red line, the one under the "W."

They also traced Madrid’s route south along the Chama (the blue line north of Tierra Amarilla) down to the red road (Route 64), across that road west, then back south along the river towards Cuba. They ended at Zia.

Madrid called the land between what is now Tres Piedras and the Chama the Sierra Florida. It was the first time Spaniards had been there, and the pueblo warriors seem to have been beyond their usual range. Hendricks and Wilson think Madrid may have continued north to the Río de los Piños at the Colorado border, gone west, and down the Chama. They did not use the modern way over the Tusas mountains, Route 64.

When he returned in 1703, differences between bands were becoming clear. Navajo attacked from the north and west. Faraón Apache came from the east.

In 1704, de Vargas led a force against the Faraón in the Sandías that mustered in Bernalillo. The war captain from Santa Clara, Juan Roque, was there with four men. Lorenzo brought five men from San Juan.

By the time Francisco Cuervo arrived to replace de Vargas in 1705, the Navajo had become more dangerous. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso twice. He immediately stationed presidio troops at the most exposed points, including Santa Clara on the west side of the Río Grande.

In March, Roque de Madrid pursued them with 65 men. They included soldiers from the presidio, the men assigned to Santa Clara, and the militia. In August, Cuervo sent him north from San Juan to follow the Navajo into their homeland. He went through uncharted territory north of Taos and west of the Continental Divide. When he returned he remarked, "we could make war on them again with greater advantage than at present, because all the men are now experienced in this land, the ways in and out, and we would return with more food."

The Navajo had made peace with Cuervo, not with the entity called Nuevo México. José Chacón took over as governor in 1707 during a severe drought. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso in 1708. Madrid was dispatched with presidio forces, settlers from Santa Cruz, and auxiliaries from the three affected pueblos.

Navajo raids continued. They stole animals from Santa Clara in 1709. Chacón sent troops to no avail, and so did his successor, Juan Flores Mogollón. Soldiers now knew about the upper reaches of the Chama river and followed it directly. Madrid attacked again in March of 1714, and killed 30 Navajo. Raids stopped. Flores took away the pueblos’ guns in July.

Notes:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s 1705 campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; it gives no details on the men who mustered, refers to the local auxiliaries as Tewa, and lists a few men who were his staff. Only Naranjo was from Santa Cruz.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Vargas, Diego de. War edicts, 27 March-2 April, 1704, in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

Map: United States Department of the Interior. Geological Survey. National Atlas of the United States of America. "New Mexico," 2004.

Hendricks and Wilson reconstructed Madrid’s 1705 route up the red line at the right (Route 68) to the first river (blue line). From there (Pilar) they went west to the next red line, the one under the "W."

They also traced Madrid’s route south along the Chama (the blue line north of Tierra Amarilla) down to the red road (Route 64), across that road west, then back south along the river towards Cuba. They ended at Zia.

Madrid called the land between what is now Tres Piedras and the Chama the Sierra Florida. It was the first time Spaniards had been there, and the pueblo warriors seem to have been beyond their usual range. Hendricks and Wilson think Madrid may have continued north to the Río de los Piños at the Colorado border, gone west, and down the Chama. They did not use the modern way over the Tusas mountains, Route 64.

Labels:

01 Madrid,

02 Navajo,

02 San Juan 1-5,

02 Santa Clara 1-5

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)