The Council of Trent defined acceptance of the sacraments as "necessary for every individual" and, by implication, defined their administration as the primary responsibility of the clergy. It labeled the Protestant view that "men obtain of God, through faith alone, the grace of justification" as "anathema."

The Council proclaimed the "seven sacraments are in such wise equal to each other," but that was not the operative view of them in Nuevo México. Baptism was the most widely accepted because even little children who "have not actual faith" were "reckoned amongst the faithful."

It was so important laymen were allowed to perform the rite with "true and natural water" in emergencies. This occurred five times in Santa Cruz between 1733 and 1759. Phelipe Romero baptized Juana Naranjo in 1739, Antonio Bernal blessed Juana Luiza Martín in 1745, and Julian Madrid committed Gervacio Duran in 1753. In 1753 Joanna Archuleta was baptized by necessity, as was Juan Domingo in 1758.

The fact the rite defined one as a member of the church’s community was seen as a form of protection against the Inquisition, which still existed as a threat. While the Council denied the act freed men from "the observance of the whole law of Christ," people seemed to think having their children baptized as they had been was sufficient evidence of their sanctity.

Men had the captives they purchased from the Comanche baptized. The friars argued this step alone made it impossible for Natives to return to their bands. The men who recruited their godparents instead may have wanted validation of the purchase and justification for the subsequent presence of hitherto unknown unmarried young men and women in their households.

The idea of baptism as protection was absorbed by the Jicarilla Apache, who were willing to submit to it in exchange for military support. That may have been the view of the Navajo who listened to Carlos Delgado and José de Irigoyen, but then rejected the corollary expectation they moved into pueblos.

The pueblos clearly saw baptism as an attempt to interfere with their traditional ways. In 1760, thirty years after Juan Miguel Menchero had decreed sacraments were to be administered for free to Natives, Juan Sanz protested any suggestion friars expected compensation. He wrote:

"In baptizing the children, it is necessary for the father to ascertain carefully when they are born, for if he does not, they do not bring children to be baptized, and if they had to pay an obvention, would they ever be baptized?"

The rite of matrimony probably was more accepted by those with property, since it and wills were the instruments that ensured the orderly transfer of assets from generation to generation. Others may have avoided the sacrament to elude interference by friars into their lives. The diligencias matrimoniales not only cost money but enforced prohibitions against certain kinds of marriages between kin not related by blood, like that between a man and his dead wife’s sister. Dispensations were possible, but added delays and notary fees.

The pueblos were more resistant because friars saw it as their duty to impose western concepts of family. Sanz noted, "if it is for obliging them to marry, this is done when they are discovered in concubinage, which is an invariable custom among them."

Carlos Delgado’s comments, quoted in the post for 24 February 2016, that friars had to travel at all hours suggested the more faithful accepted the need for "Extreme Unction." It was the only duty that required a priest to leave the precincts of the church.

The sacrament was merged with two others in these years, penance and the Eucharist, into the belief people needed to attend mass once a year, and to attend mass they had to confess once a year. This was clearly the doctrinal point behind Benito Crespo’s complaints discussed in the post for 3 April 2016 that many missions in Nuevo México did not meet this minimum.

Actual burial practices were rarely recorded. Angélico Chávez noted the burial registers didn’t begin until 1726 at Santa Cruz, Santa Clara and San Juan del Caballeros. The cover of the one used at Santa Cruz until 1768 was "limp tan leather." The flyleaf was "decorated with heavy scroll border, skulls, skeletons."

Deposition of bodies apparently was a private matter. In 1744, Menchero noted at Rancho del Embudo, where there were constant attacks by indios bárbaros, "The whole place is full of crosses." In 1776, Francisco Domínguez noted La Soledad, the settlement founded by Sebastían Martín north of San Juan, had "a little cemetery."

The pueblos treated death as a another aspect of their lives they wanted sheltered from clerical oversight. Sanz was correct when he observed people living in the pueblos "would die without confession and the father would not know about it," but probably misled when he thought "they would carry the body off to a ravine in order to avoid obvention."

Confirmations were rare. The Council of Trent had explicitly stated the sacrament could only be performed by a bishop. In 1760, Pedro Tamarón recorded he confirmed 96 at Embudo and that "they were prepared for it, and they recited the catechism." He did not mention performing the sacrament at either of the two local pueblos or La Cañada.

The seventh sacrament, the ordination of priests, was not practiced locally. This was the one the Council had in mind when it said "all (the sacraments) are not necessary for every individual."

Notes: On mission to Navajo, see post for 10 April 2016. I don’t know whether either group of Athabascan speakers saw some other value in having "water thrown upon" their heads. I haven’t found any comments of their beliefs prior to their contact with French and Spanish missionaries. Fees were discussed in the post for 27 March 2016. The use of skeletons and skulls as decorative motifs was mentioned in the post for 10 April 2016.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Chávez, Angélico. Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900, 1957.

Council of Trent. "On the Sacraments, First Decree and Canons," 3 March 1547. I’m quoting this since some things were changed by the Second Vatican Council held between 1962 and 1965. Some sacraments, especially penance, later acquired additional significance in northern New Mexico.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez in The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Menchero, Juan Miguel. Declaration, 10 May 1744, Santa Bárbara; translation in Bandelier.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 Novmber1760; translation in Bandelier. [Esp Hist I17] p475

Tamarón y Romeral, Pedro. The Kingdom of New Mexico, 1760, translation in Eleanor B. Adams, Bishop Tamarón’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760, 1954.

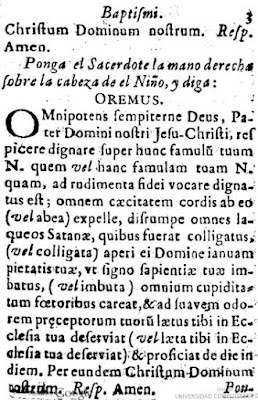

Graphics: First page on baptisms from Agustín de Vetancurt, Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, 1729 edition, discussed in the post for 1 May 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment