Diego de Vargas left Nuevo México believing local indios bárbaros fell into two groups: Athabaskan speakers and Shoshone speakers. Navajo and Apache were grouped together in the first, Ute and Comanche in the second.

When he returned in 1703, differences between bands were becoming clear. Navajo attacked from the north and west. Faraón Apache came from the east.

In 1704, de Vargas led a force against the Faraón in the Sandías that mustered in Bernalillo. The war captain from Santa Clara, Juan Roque, was there with four men. Lorenzo brought five men from San Juan.

By the time Francisco Cuervo arrived to replace de Vargas in 1705, the Navajo had become more dangerous. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso twice. He immediately stationed presidio troops at the most exposed points, including Santa Clara on the west side of the Río Grande.

In March, Roque de Madrid pursued them with 65 men. They included soldiers from the presidio, the men assigned to Santa Clara, and the militia. In August, Cuervo sent him north from San Juan to follow the Navajo into their homeland. He went through uncharted territory north of Taos and west of the Continental Divide. When he returned he remarked, "we could make war on them again with greater advantage than at present, because all the men are now experienced in this land, the ways in and out, and we would return with more food."

The Navajo had made peace with Cuervo, not with the entity called Nuevo México. José Chacón took over as governor in 1707 during a severe drought. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso in 1708. Madrid was dispatched with presidio forces, settlers from Santa Cruz, and auxiliaries from the three affected pueblos.

Navajo raids continued. They stole animals from Santa Clara in 1709. Chacón sent troops to no avail, and so did his successor, Juan Flores Mogollón. Soldiers now knew about the upper reaches of the Chama river and followed it directly. Madrid attacked again in March of 1714, and killed 30 Navajo. Raids stopped. Flores took away the pueblos’ guns in July.

Notes:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s 1705 campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; it gives no details on the men who mustered, refers to the local auxiliaries as Tewa, and lists a few men who were his staff. Only Naranjo was from Santa Cruz.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Vargas, Diego de. War edicts, 27 March-2 April, 1704, in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

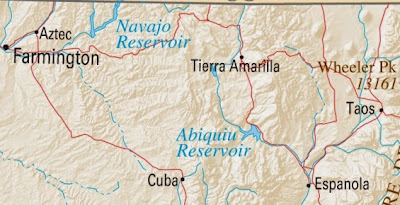

Map: United States Department of the Interior. Geological Survey. National Atlas of the United States of America. "New Mexico," 2004.

Hendricks and Wilson reconstructed Madrid’s 1705 route up the red line at the right (Route 68) to the first river (blue line). From there (Pilar) they went west to the next red line, the one under the "W."

They also traced Madrid’s route south along the Chama (the blue line north of Tierra Amarilla) down to the red road (Route 64), across that road west, then back south along the river towards Cuba. They ended at Zia.

Madrid called the land between what is now Tres Piedras and the Chama the Sierra Florida. It was the first time Spaniards had been there, and the pueblo warriors seem to have been beyond their usual range. Hendricks and Wilson think Madrid may have continued north to the Río de los Piños at the Colorado border, gone west, and down the Chama. They did not use the modern way over the Tusas mountains, Route 64.

Showing posts with label 02 San Juan 1-5. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 02 San Juan 1-5. Show all posts

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Pueblo Relations

Diego de Vargas returned as governor of Nuevo México in 1703. It’s not clear if he realized how much the settlement had changed since he left in 1697. Pueblo relations were close to those between Natives and Spaniards in New Spain, and would become completely rationalized by the man who became governor in 1705, Francisco Cuervo.

Encomiendas were gone. The only residual was Cuervo’s expectation that "Christian Catholics" in the pueblos would take "care to till and cultivate the fields" for the "father minister" for the "regular maintenance of his person."

Repartimiento was nearly gone. The only labor quotas that survived were those imposed by governors for defense. Pueblos were required to send their best warriors for expeditions against bárbaros.

Wage labor had replaced both in the years immediately after Juan de Oñate trekked north and east from Nueva Vizcaya in 1588. Natives worked the silver mines and lived in homogenous communities surrounding Zacatecas and other mining towns. Some arrived as auxiliaries in local battles against nomadic bands in northern México.

Thus, the herbalist at San Juan, Juan, would have been paid for curing the women mentioned by Leonor Domínguez in 1708. Likewise, when she went for lime, she would have been expected to trade or pay for it. Disputes only arose when Españoles, like Felipe Morgana or Antonia Luján, felt they hadn’t received what they’d been promised.

The position of Catarina Luján, the lame woman accused of witchcraft by Leonor, is less clear. She testified "Father Fray Juan Minguez took this declarant to the said Town to clean his cell" in 1708. This may have been seen as "regular maintenance of his person" rather than paid work.

The pueblos assiduously defended their rights. In 1707 San Juan complained Roque de Madrid forced members to work on Sunday and was too authoritarian. It had the alcalde sign its complaint, but the governor, Jose Chacón, didn’t pursue it.

Friars later complained Chacón and his alcaldes were forcing people to work without pay. The viceroy sent a reprimand. His successor, Juan Flores Magollón, canvassed the pueblos in 1712. All said their members were paid for services, and none had been forcibly removed.

The major change in pueblo relations came with the use of auxiliaries. Oakah Jones noted that, before de Vargas left, he used warriors from one pueblo to attack another. When he died in 1704, he was using presidio, settler and pueblo troops together against common enemies. His earlier negotiations for submission had been converted into obligations of protection held by the pueblos.

Notes: See "Chronicles of Leonor" for more on Juan, Catarina Luján, Leonor Domínguez, Antonia Luján, and Felipe Morgana.

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978; on complaint against Madrid.

Bakewell, P. J. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico, Zacatecas 1546-1700, 1971.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Frank, Andre Gunder. Mexican Agriculture 1521-1630, 1979.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, collected by Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, included in Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett; quotation from Cuervo.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914; quotation from Luján.

Encomiendas were gone. The only residual was Cuervo’s expectation that "Christian Catholics" in the pueblos would take "care to till and cultivate the fields" for the "father minister" for the "regular maintenance of his person."

Repartimiento was nearly gone. The only labor quotas that survived were those imposed by governors for defense. Pueblos were required to send their best warriors for expeditions against bárbaros.

Wage labor had replaced both in the years immediately after Juan de Oñate trekked north and east from Nueva Vizcaya in 1588. Natives worked the silver mines and lived in homogenous communities surrounding Zacatecas and other mining towns. Some arrived as auxiliaries in local battles against nomadic bands in northern México.

Thus, the herbalist at San Juan, Juan, would have been paid for curing the women mentioned by Leonor Domínguez in 1708. Likewise, when she went for lime, she would have been expected to trade or pay for it. Disputes only arose when Españoles, like Felipe Morgana or Antonia Luján, felt they hadn’t received what they’d been promised.

The position of Catarina Luján, the lame woman accused of witchcraft by Leonor, is less clear. She testified "Father Fray Juan Minguez took this declarant to the said Town to clean his cell" in 1708. This may have been seen as "regular maintenance of his person" rather than paid work.

The pueblos assiduously defended their rights. In 1707 San Juan complained Roque de Madrid forced members to work on Sunday and was too authoritarian. It had the alcalde sign its complaint, but the governor, Jose Chacón, didn’t pursue it.

Friars later complained Chacón and his alcaldes were forcing people to work without pay. The viceroy sent a reprimand. His successor, Juan Flores Magollón, canvassed the pueblos in 1712. All said their members were paid for services, and none had been forcibly removed.

The major change in pueblo relations came with the use of auxiliaries. Oakah Jones noted that, before de Vargas left, he used warriors from one pueblo to attack another. When he died in 1704, he was using presidio, settler and pueblo troops together against common enemies. His earlier negotiations for submission had been converted into obligations of protection held by the pueblos.

Notes: See "Chronicles of Leonor" for more on Juan, Catarina Luján, Leonor Domínguez, Antonia Luján, and Felipe Morgana.

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978; on complaint against Madrid.

Bakewell, P. J. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico, Zacatecas 1546-1700, 1971.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Frank, Andre Gunder. Mexican Agriculture 1521-1630, 1979.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, collected by Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, included in Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett; quotation from Cuervo.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914; quotation from Luján.

Sunday, April 26, 2015

Creation Tales

Creation tales attempt the impossible: imagining something outside the world we know.

The key metaphor used by King James’ translators of Genesis was formlessness:

"And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters."

They shared Francis Bacon’s view, mentioned in the last posting, that nothing was true until verified. The discovery the world wasn’t flat had shaken their faith in absolutes. They were willing to consider what once had been unthinkable.

The English College at Douay assumed a familiar world, one that had form but simply was vacant:

"And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters."

In both translations, God created light on the first day, the firmament on the second, and land on the third. When He created man on the sixth day, He placed Adam in a garden.

San Juan divided the primal world into "a big lake, Ohange pokwinge, Sand Lake" and the world underground. When humans emerged, they came through the water.

Morris Opler heard two versions from Jicarilla. In the first, Black Sky and Earth Woman created the Hactcin who lived in the underworld. In the second, there was nothing but darkness, water and cyclone. The spirits existed and they created the male Sky and female Earth, the one lying above the other.

Spirits in both versions created the sun and moon. When shamans amongst the group asserted they were the true creators, Black Hactcin threw the sun and moon out of the underworld. When those who would be human missed the light, the Hactcin created a mountain with a hole through which they climbed.

Some would say Native American groups borrowed the idea of primal water from the Roman Catholics, who translated Saint Jerome’s version of older Latin texts that came from Greek translations of Hebrew and Aramaic.

Biblical scholars have argued Jews borrowed their ideas from the Enuma elish epic of the Mesopotamians. The word "deep" in Hebrew is thought to refer to their evil ocean goddess, Tiamat, who was fighting for control with the supreme god Anu. Marduk slew her, and slit her body to create sky and earth.

Early Jewish codifiers weren’t as interested as San Juan or the Jicarilla in imaging a time before the present. They lavished more detail on Noah than they did the first chapter of Genesis. They wanted to establish their line of descent from the beginning, and were willing to accept the then current definition of that time. They kept the Persian narrative of the first seven days, but replaced references to a pantheon with a single god.

Freudian analysts would argue each group created a similar tale by extrapolating from a shared human experience, emergence from the watery, dark womb. Jungians treat water as a universal symbol for the unconscious each individual must explore to become fully human. For them, the general is a reflection of the inner life of the individual.

A few would simply say the similarities in origin tales arose from some common cultural core passed on since the stone age. Others would argue the shared parts were trivial compared to the differences that expressed the unique cultural heritage of each which had survived interactions with others. It doesn’t matter if people borrowed their visions of the unimaginable. What matters is how they conceived human experience.

Notes: P is generally considered to be the transcriber of the first two chapters of Genesis. He is thought to have been a priest around 500 bc, after the Jews returned from exile in Babylon where they would have been exposed to current Mesopotamian ideas.

Douay College. The Holy Bible, Holy Family edition of the Catholic Bible, Old Testament in the Douay-Calloner text, edited by John P. O’Connell, 1950. Sons of the Holy Family are responsible for the churches in Santa Cruz and Chimayó. Genesis 1:2.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis Chapters 1-17, 1990.

James I. The Holy Bible, conformable to that edition of 1611, commonly known as the authorized or King James version, The World Publishing Company, nd. Genesis 1:2.

Opler, Morris Edward. Myths and Tales of the Jicarilla Apache Indians, 1938. His sources were Cevero Caramillo, John Chopari, Alasco Tisnado, and Juan Julian.

_____. "A Summary of Jicarilla Apache Culture," American Anthropologist 38:202-223:1936.

Parsons, Elsie Clews. Tewa Tales, 1926. She did not name her source for tale 1, but described him as "a man of about sixty" and added "his sister’s daughter, a woman of forty, was a good interpreter."

Speiser, E. A. Genesis, 1964.

The key metaphor used by King James’ translators of Genesis was formlessness:

"And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters."

They shared Francis Bacon’s view, mentioned in the last posting, that nothing was true until verified. The discovery the world wasn’t flat had shaken their faith in absolutes. They were willing to consider what once had been unthinkable.

The English College at Douay assumed a familiar world, one that had form but simply was vacant:

"And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters."

In both translations, God created light on the first day, the firmament on the second, and land on the third. When He created man on the sixth day, He placed Adam in a garden.

San Juan divided the primal world into "a big lake, Ohange pokwinge, Sand Lake" and the world underground. When humans emerged, they came through the water.

Morris Opler heard two versions from Jicarilla. In the first, Black Sky and Earth Woman created the Hactcin who lived in the underworld. In the second, there was nothing but darkness, water and cyclone. The spirits existed and they created the male Sky and female Earth, the one lying above the other.

Spirits in both versions created the sun and moon. When shamans amongst the group asserted they were the true creators, Black Hactcin threw the sun and moon out of the underworld. When those who would be human missed the light, the Hactcin created a mountain with a hole through which they climbed.

Some would say Native American groups borrowed the idea of primal water from the Roman Catholics, who translated Saint Jerome’s version of older Latin texts that came from Greek translations of Hebrew and Aramaic.

Biblical scholars have argued Jews borrowed their ideas from the Enuma elish epic of the Mesopotamians. The word "deep" in Hebrew is thought to refer to their evil ocean goddess, Tiamat, who was fighting for control with the supreme god Anu. Marduk slew her, and slit her body to create sky and earth.

Early Jewish codifiers weren’t as interested as San Juan or the Jicarilla in imaging a time before the present. They lavished more detail on Noah than they did the first chapter of Genesis. They wanted to establish their line of descent from the beginning, and were willing to accept the then current definition of that time. They kept the Persian narrative of the first seven days, but replaced references to a pantheon with a single god.

Freudian analysts would argue each group created a similar tale by extrapolating from a shared human experience, emergence from the watery, dark womb. Jungians treat water as a universal symbol for the unconscious each individual must explore to become fully human. For them, the general is a reflection of the inner life of the individual.

A few would simply say the similarities in origin tales arose from some common cultural core passed on since the stone age. Others would argue the shared parts were trivial compared to the differences that expressed the unique cultural heritage of each which had survived interactions with others. It doesn’t matter if people borrowed their visions of the unimaginable. What matters is how they conceived human experience.

Notes: P is generally considered to be the transcriber of the first two chapters of Genesis. He is thought to have been a priest around 500 bc, after the Jews returned from exile in Babylon where they would have been exposed to current Mesopotamian ideas.

Douay College. The Holy Bible, Holy Family edition of the Catholic Bible, Old Testament in the Douay-Calloner text, edited by John P. O’Connell, 1950. Sons of the Holy Family are responsible for the churches in Santa Cruz and Chimayó. Genesis 1:2.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis Chapters 1-17, 1990.

James I. The Holy Bible, conformable to that edition of 1611, commonly known as the authorized or King James version, The World Publishing Company, nd. Genesis 1:2.

Opler, Morris Edward. Myths and Tales of the Jicarilla Apache Indians, 1938. His sources were Cevero Caramillo, John Chopari, Alasco Tisnado, and Juan Julian.

_____. "A Summary of Jicarilla Apache Culture," American Anthropologist 38:202-223:1936.

Parsons, Elsie Clews. Tewa Tales, 1926. She did not name her source for tale 1, but described him as "a man of about sixty" and added "his sister’s daughter, a woman of forty, was a good interpreter."

Speiser, E. A. Genesis, 1964.

Thursday, April 23, 2015

Origin Tales

Origin tales explain how we humans came to be.

The ones of Spanish settlers in the Española valley, San Juan pueblo and Jicarilla Apache all began as oral traditions passed from generation to generation. Native American tales remained verbal. Those of the Españoles moved in and out of written tradition. At the time Juan de Oñate led them north into the wilderness, only priests had Bibles, and they were in Latin, not Spanish.

When James I issued an authoritative translation in 1611, twenty-three years after Oñate arrived at San Juan, the English king’s scholars wrote:

"And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breathe of life; and man became a living soul."

Roman Catholics at the English College of Douay in France had published an alternative translation in 1609 that read:

"And the Lord God formed man of the slime of the earth and breathed into his face the breath of life, and man became a living soul."

The account of Adam’s creation assumed a single, concentrated source of power that existed before humankind. By the time Genesis was translated into English, that power was male. It stretched in an unbroken line from the monarchs to the popes to the disciples to Christ. For Jews, it extended back through the kings to David and Solomon to Adam himself.

San Juan assumed a world of powers diffused among the unmade people under the lake and the spirit animals living below the ground. The future human the spirit people selected as a leader had to be both male and female, embody the gifts of each.

"Next, the people realized they needed a leader who was both male and female. When they found him, they sent him to explore. Kanyotsanyotse tetseenubu’ta, commonly called Yellow Boy, was the first made person."

The Jicarilla said "all the Hactcin were here from the beginning," but one spirit, Black Hactcin, was more powerful. After he made the animals, he "traced an outline of a figure on the ground, making it just like his own body, for the Hactcin was shaped just as we are today. He traced the outline with pollen" and brought it to life.

Genesis began with God creating a male and making a garden for him to inhabit. Next he formed "every beast of the field and every fowl in the air," but "for Adam there was not found an help meet for him." So next:

"the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept; and he took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof;"

Soon after he commissioned this translation, James made Francis Bacon his solicitor general. The intellectual world was poised for the great leap in thinking patterns signified by the Novum Organum Bacon would publish in 1620. The translators anticipated the neutral discourse of science when they chose the word "cause."

The Duoay version was closer to the Hebrew and the medieval world of witchcraft spells. They wrote:

"Then the Lord God cast a deep sleep upon Adam: and when he was fast asleep, he took one of his ribs and filled up flesh for it."

The Jicarilla used a trance. They told Morris Opler, the Hactcin used lice to make the first man sleepy.

"He was dreaming and dreaming. He dreamt that someone, a girl, was sitting beside him."

"He woke up. The dream had come true."

The older San Juan man who retold the origin tale for Elsie Clews Parsons did not feel the same need to explain the separation of male and female. They existed, coequal, from the beginning.

History begins in Genesis when Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden for testing the tree of knowledge. Life in the outside world is a punishment for being sinful, for being curious, for being human. In San Juan and Jicarilla, the migration from the underworld is voluntary and desired, a reward for curiosity.

Notes:

Douay College. The Holy Bible, Holy Family edition of the Catholic Bible, Old Testament in the Douay-Calloner text, edited by John P. O’Connell, 1950. Sons of the Holy Family are responsible for the churches in Santa Cruz and Chimayó. Genesis 2:7 and 2:21.

James I. The Holy Bible, conformable to that edition of 1611, commonly known as the authorized or King James version, The World Publishing Company, nd. Genesis 2:7, 2:20 and 2:21.

Opler, Morris Edward. Myths and Tales of the Jicarilla Apache Indians, 1938. His sources were Cevero Caramillo, John Chopari, Alasco Tisnado, and Juan Julian.

Parsons, Elsie Clews. Tewa Tales, 1926. She did not name her source for tale 1, but described him as "a man of about sixty" and added "his sister’s daughter, a woman of forty, was a good interpreter."

The ones of Spanish settlers in the Española valley, San Juan pueblo and Jicarilla Apache all began as oral traditions passed from generation to generation. Native American tales remained verbal. Those of the Españoles moved in and out of written tradition. At the time Juan de Oñate led them north into the wilderness, only priests had Bibles, and they were in Latin, not Spanish.

When James I issued an authoritative translation in 1611, twenty-three years after Oñate arrived at San Juan, the English king’s scholars wrote:

"And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breathe of life; and man became a living soul."

Roman Catholics at the English College of Douay in France had published an alternative translation in 1609 that read:

"And the Lord God formed man of the slime of the earth and breathed into his face the breath of life, and man became a living soul."

The account of Adam’s creation assumed a single, concentrated source of power that existed before humankind. By the time Genesis was translated into English, that power was male. It stretched in an unbroken line from the monarchs to the popes to the disciples to Christ. For Jews, it extended back through the kings to David and Solomon to Adam himself.

San Juan assumed a world of powers diffused among the unmade people under the lake and the spirit animals living below the ground. The future human the spirit people selected as a leader had to be both male and female, embody the gifts of each.

"Next, the people realized they needed a leader who was both male and female. When they found him, they sent him to explore. Kanyotsanyotse tetseenubu’ta, commonly called Yellow Boy, was the first made person."

The Jicarilla said "all the Hactcin were here from the beginning," but one spirit, Black Hactcin, was more powerful. After he made the animals, he "traced an outline of a figure on the ground, making it just like his own body, for the Hactcin was shaped just as we are today. He traced the outline with pollen" and brought it to life.

Genesis began with God creating a male and making a garden for him to inhabit. Next he formed "every beast of the field and every fowl in the air," but "for Adam there was not found an help meet for him." So next:

"the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept; and he took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof;"

Soon after he commissioned this translation, James made Francis Bacon his solicitor general. The intellectual world was poised for the great leap in thinking patterns signified by the Novum Organum Bacon would publish in 1620. The translators anticipated the neutral discourse of science when they chose the word "cause."

The Duoay version was closer to the Hebrew and the medieval world of witchcraft spells. They wrote:

"Then the Lord God cast a deep sleep upon Adam: and when he was fast asleep, he took one of his ribs and filled up flesh for it."

The Jicarilla used a trance. They told Morris Opler, the Hactcin used lice to make the first man sleepy.

"He was dreaming and dreaming. He dreamt that someone, a girl, was sitting beside him."

"He woke up. The dream had come true."

The older San Juan man who retold the origin tale for Elsie Clews Parsons did not feel the same need to explain the separation of male and female. They existed, coequal, from the beginning.

History begins in Genesis when Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden for testing the tree of knowledge. Life in the outside world is a punishment for being sinful, for being curious, for being human. In San Juan and Jicarilla, the migration from the underworld is voluntary and desired, a reward for curiosity.

Notes:

Douay College. The Holy Bible, Holy Family edition of the Catholic Bible, Old Testament in the Douay-Calloner text, edited by John P. O’Connell, 1950. Sons of the Holy Family are responsible for the churches in Santa Cruz and Chimayó. Genesis 2:7 and 2:21.

James I. The Holy Bible, conformable to that edition of 1611, commonly known as the authorized or King James version, The World Publishing Company, nd. Genesis 2:7, 2:20 and 2:21.

Opler, Morris Edward. Myths and Tales of the Jicarilla Apache Indians, 1938. His sources were Cevero Caramillo, John Chopari, Alasco Tisnado, and Juan Julian.

Parsons, Elsie Clews. Tewa Tales, 1926. She did not name her source for tale 1, but described him as "a man of about sixty" and added "his sister’s daughter, a woman of forty, was a good interpreter."

Sunday, April 19, 2015

Santa Cruz Medicine

In the early years after the Reconquest, Santa Cruz lacked the skills it needed to maintain Spanish medical culture.

No midwives were mentioned in the lists of Mexico City colonists, and there may have been none. Two women died in childbirth on the journey north: María López de Arteaga, wife of Manuel Vallejo González, and María Antonia Chirinos, wife of Juan Manuel Martínez de Cervantes.

In Spain, when the imbalance between blood and the other three humors was serious, a barber was engaged to bleed the person. One barber had come with the group from Mexico City, Nicolás Moreno Trujillo, but he returned south in 1705. Angélico Chávez said another, Antonio Durán de Armijo, came from Zacatecas. He lived in Santa Fé.

By 1715, Francisco Xavier Romero was working in Santa Cruz as a barber. When he came from Mexico City, he listed himself as a baker and miller. Chávez identified him as a shoemaker.

When one of the other humors was deemed the problem, the body was purged with a herbal emetic.

There probably were no herbalists. The abilities to identify and remember plants can be transferred, but not the lore. The first summer in Santa Cruz, men complained "poisonous herbs" were killing their stock.

Records of pueblo medical practice in 1700 probably do not exist. If members had been reticent before the trial of 47 medicine men in 1675, they would have been mute after the Reconquest. Popé had been one of those tried and freed.

A few reports have survived that describe medical relations between San Juan and its neighbors.

In 1704, Felipe Morgana filed a complaint against Juan Chiyo for failing to cure his blindness.

In 1708, Leonor Domínguez reported Augustina Romero, María Luján and Ana María de la Concepción Bernal had been bewitched. She said the healer was Juanchillo. He said he had treated the first two with beneficial herbs.

In the same deposition, Leonor said she had been bewitched, but she did not seek help from a native healer.

In 1715, Antonia Luján claimed Francisca Caza had bewitched her when she refused to drink a potion she had been offered to improve her lot. Soon after, she began to suffer pain. She paid the woman to cure her, but didn’t get well. She then paid another native woman to cure her with an herb from Galisteo. When that failed, she complained to the Santa Fé alcalde. He only took up the case when she added she believed her husband was seeing Caza.

In two cases, the herbal healer was the same man. Leonor identified him as Juanchillo, a carpenter and herbal healer. His wife was listed in one place as Chepa, and another as Josefa. Felipe Morgana called him Juan Chiyo. Tracy Brown identified him as "Juan el carpentero."

The one who dealt in potions, Francisca Caza, was from San Juan, but lived in Santa Fé. Her husband, Francisco Cuervo, was a Jumano Indian, perhaps from the Salinas area.

In the case mentioned in the posting for 25 March 2005, Ines de Aspeitia used a charm, not a herbal potion. She was described as a native of Mexico City and "dark skinned" in 1693.

Notes:

Angulo, José de Angulo. List of colonists from Mexico City, 7 September 1693, in Kessell.

Brown, Tracy L. Pueblo Indians and Spanish Colonial Authority, 2013.

Chávez, Angélico. Origins of New Mexico Families, 1992 revised edition; discusses Felipe Morgana.

Enbright, Malcolm and Rick Hendricks. The Witches of Abiquiu, 2006; discusses Antonia Luján.

Kessell, John L., Rick Hendricks and Meredith Dodge. To the Royal Crown Restored, 1995.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico, 1914; volume 1 has the 1696 request to move because of poisonous herbs; volume 2 discusses Leonor Domínguez and Augustina Romero.

Velázquez de la Cadena, Pedro. List of families going to New Mexico, 4 September 1693, in Kessell.

No midwives were mentioned in the lists of Mexico City colonists, and there may have been none. Two women died in childbirth on the journey north: María López de Arteaga, wife of Manuel Vallejo González, and María Antonia Chirinos, wife of Juan Manuel Martínez de Cervantes.

In Spain, when the imbalance between blood and the other three humors was serious, a barber was engaged to bleed the person. One barber had come with the group from Mexico City, Nicolás Moreno Trujillo, but he returned south in 1705. Angélico Chávez said another, Antonio Durán de Armijo, came from Zacatecas. He lived in Santa Fé.

By 1715, Francisco Xavier Romero was working in Santa Cruz as a barber. When he came from Mexico City, he listed himself as a baker and miller. Chávez identified him as a shoemaker.

When one of the other humors was deemed the problem, the body was purged with a herbal emetic.

There probably were no herbalists. The abilities to identify and remember plants can be transferred, but not the lore. The first summer in Santa Cruz, men complained "poisonous herbs" were killing their stock.

Records of pueblo medical practice in 1700 probably do not exist. If members had been reticent before the trial of 47 medicine men in 1675, they would have been mute after the Reconquest. Popé had been one of those tried and freed.

A few reports have survived that describe medical relations between San Juan and its neighbors.

In 1704, Felipe Morgana filed a complaint against Juan Chiyo for failing to cure his blindness.

In 1708, Leonor Domínguez reported Augustina Romero, María Luján and Ana María de la Concepción Bernal had been bewitched. She said the healer was Juanchillo. He said he had treated the first two with beneficial herbs.

In the same deposition, Leonor said she had been bewitched, but she did not seek help from a native healer.

In 1715, Antonia Luján claimed Francisca Caza had bewitched her when she refused to drink a potion she had been offered to improve her lot. Soon after, she began to suffer pain. She paid the woman to cure her, but didn’t get well. She then paid another native woman to cure her with an herb from Galisteo. When that failed, she complained to the Santa Fé alcalde. He only took up the case when she added she believed her husband was seeing Caza.

In two cases, the herbal healer was the same man. Leonor identified him as Juanchillo, a carpenter and herbal healer. His wife was listed in one place as Chepa, and another as Josefa. Felipe Morgana called him Juan Chiyo. Tracy Brown identified him as "Juan el carpentero."

The one who dealt in potions, Francisca Caza, was from San Juan, but lived in Santa Fé. Her husband, Francisco Cuervo, was a Jumano Indian, perhaps from the Salinas area.

In the case mentioned in the posting for 25 March 2005, Ines de Aspeitia used a charm, not a herbal potion. She was described as a native of Mexico City and "dark skinned" in 1693.

Notes:

Angulo, José de Angulo. List of colonists from Mexico City, 7 September 1693, in Kessell.

Brown, Tracy L. Pueblo Indians and Spanish Colonial Authority, 2013.

Chávez, Angélico. Origins of New Mexico Families, 1992 revised edition; discusses Felipe Morgana.

Enbright, Malcolm and Rick Hendricks. The Witches of Abiquiu, 2006; discusses Antonia Luján.

Kessell, John L., Rick Hendricks and Meredith Dodge. To the Royal Crown Restored, 1995.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico, 1914; volume 1 has the 1696 request to move because of poisonous herbs; volume 2 discusses Leonor Domínguez and Augustina Romero.

Velázquez de la Cadena, Pedro. List of families going to New Mexico, 4 September 1693, in Kessell.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)