Clergymen in Ciudad de México appealed to Nuestra Señora de los Remedios before Guadalupe in the 1737 matlazáhuatl epidemic because she had been used in processions against smallpox since 1575. The most recent had occurred in 1733 and 1734.

Angélico Chávez found evidence a smallpox epidemic had ravaged Santa Ana from April to August of 1733. He also saw records in church archives of many deaths between May and June in Santa Fé and of 15 deaths in September at Laguna. Frederic Athearn found similar records for Jémez that year.

Smallpox had become routine, arriving once a generation. Robert McCaa said, everyone in Nueva España was "taught to prepare themselves for the eruption of the pustules. Once erupted, they were comforted, given water, food, and blankets, and cautioned not to bath or scratch until the scabs had fallen away."

Quarantine was the first response in Boston in 1721. Incoming ships were impounded, and guards stationed at the House of Representatives to keep out unscreened people. When the disease first reached Nueva España in 1520, McCaa said, "for the Nahua, quarantine was a completely alien notion." From the evidence of processions, it probably still wasn’t widely accepted in 1733.

Medical practice in Europe was beginning to change. Reports had been received from Turkey attesting to the effectiveness of inoculation with a weakened strain of the Variola virus. In Boston, a Puritan minister, Cotton Mather, passed on testimony from his slave, Onesimus, that he had been inoculated as a child in Africa. A friend tried the procedure on his own son and two slaves during the epidemic of 1721. When they survived, he treated another 194. Only six died. The normal death rate was 1 in 6.

The practice spread slowly. In 1743, the foundling hospital in London was inoculating its charges. Many young women who came to the city to work as servants had themselves treated before they sought employment. Inoculation still required quarantine to prevent spread of the deliberately introduced pathogen. The treated often bristled at isolation.

Smallpox returned to Mexico City in 1748, and again Chávez found evidence it spread north. In Santa Fé, 68 died between July and September of unspecified causes. Pecos had an unidentified epidemic in August. The pueblo had had a smallpox outbreak in the winter of 1738.

Santa Cruz was less prepared this time than last. One problem would have been identifying the source of the disease. Since its symptoms appear within 12 days of exposure, anyone coming north from México would have died on the trip from lack of care. That suggests it was spread by contaminated trade goods. There would have been no way or reason to scrutinize them before the disease spread.

The other problem was no one was available to oversee quarantine or mass care. Nuevo México had recruited no new barbers since those who came with the Reconquest. Antonio Durán de Armijo died in Santa Fé in 1753 at age 80. Our local man, Francisco Xavier Romero, died in 1732. For reasons mentioned in the post for 13 January 2016, he probably trained no one.

It’s possible others passed the fundamentals of medical practice through their families. Angela Leyba may have been a curing woman in the Chama area before she died in 1727. Her father had been a Tiwa translator before the Pueblo Revolt, and she had been spent the interregnum in Galisteo as a captive. Her will listed a statue of Our Lady of Remedios, a cupping glass used in promoting the flow of blood, and some coral bracelets. Her husband, who died the year before, had a picture of Remedios and a "barber’s case, with five razors and stone."

Bartolomé Trujillo may have been local practitioner. He also lived in Chama where he owned a "medicine glass" in 1764. His wife, Margarita Torres, was the daughter of Leyba and her husband Cristóbal de Torres. His parents had been Cristóbal Trujillo and María de Manzanares.

There still were herbalists in Santa Cruz, although they rarely were mentioned in official records. Tomasa de Manzanares was brought into a court case in 1748 when José Manuel Trujillo, Bartolome’s nephew, accused Antonio Valverde and his sons of wounding him. The 54-year-old said, she was providing herbal cures for "for lack of surgeons in the kingdom."

Although there were no medical professionals to treat illnesses, there must have been midwives. Although I’ve found no references to them, women were having babies. Their skill level might be inferred from the records of infant deaths within the first days after birth. It must be remembered though, children who died young may have been premature or malnourished at birth or had some other condition that couldn’t be treated then, but is now.

In addition to the five infants mentioned in the post for 9 May 2016 who received emergency baptisms, two other girls died soon after. That would mean the infant mortality rate within the first 24 hours for the 1,291 infants with at least one known parent was 5.5 per 1,000 births.

For comparison, the US rate in 2013 was 2.6, which ranked it 69th among the 176 countries compared by Save the Children. Among those with 5 deaths per 1,000 were Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad. Some of the countries with 6 deaths were Paraguay and Surinam.

Notes: The cyclic nature of smallpox epidemics was discussed in the post for16 April 2015. Early barbers were discussed in the post for 19 April 2015. Coral was used later to ward off the evil eye.

Santa Cruz baptisms records indicated one child died early whose parents weren’t known. It’s hard to estimate the number of births in this group, because the baptisms also included adolescent and adult captives. In addition, servants and others without status may have had less contact with the church, so that even if a friar recorded a birth, he might not learn about a death.

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978.

Chávez, Angélico. Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900, 1957. The burial registers haven’t been transcribed by the New Mexico Genealogical Society. Chávez summarized what he read, and noted the things he though most important. The information recorded by friars no doubt varied a great deal; only a few may have bothered to record causes of deaths.

_____. Origins of New Mexico Families, 1992 revised edition. He didn’t know the relationship between María and Tomasa Manzanares; he surmised José Manuel Trujillo was the son of Bartolomé.

Christmas, Henrietta Martinez. 1598 New Mexico, blog.

Davenport, Romola, Leonard Schwarz, and Jeremy Boulton. "The Decline of Adult Smallpox in Eighteenth-Century London," Economic History Review 64:1289-1314:2011.

Leyba, Angela. Will, 1727, republished by Christmas as "Angela Leyba - Will 1727," 30 July 2014.

New Mexico Genealogical Society, New Mexico Baptisms, Santa Cruz de la Cañada Church, Volume I, 1710 to 1794, transcribed by Virginia Langham Olmstead and compiled by Margaret Leonard Windham and Evelyn Luján Baca, 1994.

McCaa, Robert. "Revisioning Smallpox in Mexico City-Tenochtitlan, 1520-1950," 27 May 2000.

Save the Children USA. State of the World’s Mothers 2013, 2013.

Torres, Cristóbal. Will, 1726, republished by Christmas as "Cristóbal Torrez - Will 1726," 28 July 2014.

Trujillo, Bartolomé. Will, 1764, republished by Christmas as "Bartolomé Trujillo - Will 1764," 22 May 2013.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914; on Trujillo versus Valverde.

Wikipedia. Entry on Cotton Mather includes discussion of smallpox and inoculation in Boston.

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Sunday, May 22, 2016

María de Guadalupe

Healers were the other source for baptismal names used in Santa Cruz between 1733 and 1759. Some were the traditional holy helpers who emerged during the years of the Bubonic plague: Barbara, Blas, Catarina, Gorge, and Margarita. Two were angels, Miguel and Rafael or Rafaela.

Others were Cayetano or Cayetana and Roque, if that name was derived from Saint Rocke who was active during the plague. Bernardo or Bernarda and Joana were healed. Rosa, a Dominican in Lima, was said to have cured lepers.

María de Guadalupe appeared for the first time in the preserved record in 1733 as the daughter of Antonia Martín and Miguel de Agüero. The next year, Antonia de Medina and Juan Luiz Martines named their daughter María de Guadalupe.

The name next was used in 1738 for Marta de Guadalupe Trujillo and in 1739 for Rosa María de Guadalupe Archuleta. After that, María Guadalupe was used twice in the mid-1740s and five times in the 1750s.

Between the baptism of the Agüero daughter and the christening of the Trujillo girl, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe was transformed in México from a miracle worker into one who reversed the course of mysterious diseases. Simultaneously, she was transformed from a cult particular to Natives into a symbol shared by all people born in Nueva España. Of the eleven girls named for her in Santa Cruz, only three were Indians, probably Apache or Comanche. The rest had two known parents.

As discussed in the post for 24 February 2016, an infection began spreading through México in 1736. No one knew what matlazáhuatl was. They could only react with procedures that worked with other epidemics like the smallpox contagion of 1733. The viceroy, Juan de Vizarrón provided food and hospitals. Robert McCaa said, he funded four doctors and six pharmacists.

The city council opted for public prayers and asked the viceroy, who was also the archbishop, to lead a novena for the Virgin of Loreto in early January of 1737. When that failed, they asked to have Nuestra Señora de los Remedios brought to the cathedral for nine more days of prayers led by Bartolomé de Ita y Para.

That too failed to stem the disease that was killing more Indians than Spaniards. Rumors were spreading. Stafford Poole said, "a sick woman in delirium saw the fever in the form of a woman on the causeway to Guadalupe." Another told of an Indian woman shouting in the sanctuary at Tepeyac, "let the Spanish die also." Stories were repeated of Indians dumping corpses into aqueducts and mixing victims’ blood in bread dough.

Members of the city’s council suggested bringing the painting of Guadalupe to the city cathedral; others objected the agave fabric was too fragile. Instead, Vizarrón suggested a pilgrimage there for a Novena. Again Ita y Parra spoke.

Still no relief. A comet was seen, probably at the end of January. In February the council agreed to swear an oath of fealty to Guadalupe, with April 27 set for the ceremony. A partial eclipse of the sun occurred March 1, beginning just after noon and lasting 90 minutes. The oath was made public after a procession and mass on May 26. By chance or divine intervention, the epidemic finally began to recede.

The intensity of veneration that followed was not chance. David Brading suggested, it became the vehicle for Mexican-born criollo clergymen to assert their independence from Spanish superiors sent by the Bourbon king.

Ita y Parra, the man who preached the "The Mother of Health sermon" at Tepeyac in 1737, was a Puebla-born Jesuit. He was explicating a new founding legend couched in Old Testament symbols when he asserted Los Remedios failed to stop the epidemic because she was from Spain, a Ruth forever homeless. Guadalupe, on the other hand, would prevail because she was, like Naomi, a native.

Matlazáhuatl arrived in Zacatecas in 1737 during a grain shortage. The city stockpiled grain and called upon its one hospital, two charitable brotherhoods, and private doctors. The Franciscans took the image of Guadalupe to all the churches in mass processions that probably spread the air-born pathogen.

Within the church, men lobbied for Guadalupe’s elevation to patroness for all Nueva España, distinct from Santiago of Spain. In 1746, delegates from city councils and cathedral chapters gathered to acclaim her patronato. Benedict XIV approved their actions in 1754.

Meanwhile, Francisco de Echávarri began supervising construction of an aqueduct to take water to the shine in Tepeyac in 1741. He had been a mine inspector. This was an extension of the civil engineering then being introduced to drain mines. The water main was completed in 1751, after the end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1748.

Guadalupe bound the criollos to the Indians against the Spaniards. Once the villa of Tepeyac had its basic necessity supplied, a college of canons was established to officiate at the shrine. To be appointed, one had to speak a native language.

Notes: Marta was probably meant to be María; her last name was written Truxillo.

Comets were still unexpected phenomena, not yet explained by science. In México, Augustinian Matías de Escobar wrote it was "a phenomenon notoriously caused by the exhalations of the seas and the corrupt humours of the body," while at Cambridge Isaac Newton suspected it might appear in 1737 based on orbits of previous comets, but wouldn’t commit himself to friends or to print. It was sighted in 1737 in Jamaica on January 26, in Philadelphia on January 27, and in Lisbon on January 29. Ignatius Kegler, a Jesuit missionary for whom it was named, observed it in Beijing on July 3.

Brading, D. A. Church and State in Bourbon Mexico, 1994.

_____. Mexican Phoenix, 2002.

Brodbeck, Roland. "Solar eclipses, Mexico, Coatzacoalcos, 1700 - 2100," 1998, in cooperation with the Swiss Astronomical Society.

Escobar, Matías de. Voces de Tritón Sonora, 1746; quoted by Brading, 1994.

Ita y Para, Bartolomé de "The Mother of Health," paraphrased by Brading, 2002.

Kronk, Gary W. Cometography, volume 1, 1999.

Lynn, W. T. "The Comet of A. D. 1737," The Observatory, May 1901.

McCaa, Robert. "Revisioning Smallpox in Mexico City-Tenochtitlán, 1520-1950," 27 May 2000.

New Mexico Genealogical Society, New Mexico Baptisms, Santa Cruz de la Cañada Church, Volume I, 1710 to 1794, transcribed by Virginia Langham Olmstead and compiled by Margaret Leonard Windham and Evelyn Luján Baca, 1994. Notes in the records varied, so they couldn’t be used to identify the ethnicity of the baptized. I’m assuming if both parents were known the parents were Españoles; if only the mother’s names were known the child was illegitimate and probably Español but possibly meztiso or captive; if no parents were known I’m assuming the baptized were captives.

Newton, Isaac. Comment on comet quoted by William Whiston and reported by Lynn; elaborated by Kronk.

Poole, Stafford. Our Lady of Guadalupe, 1995.

Raigoza Quiñónez, José Luis. "Factores de Influencia para la Transmisión y Difusión del Matlazáhuatl en Zacatecas 1737-38," Scripta Nova, August 2006.

Others were Cayetano or Cayetana and Roque, if that name was derived from Saint Rocke who was active during the plague. Bernardo or Bernarda and Joana were healed. Rosa, a Dominican in Lima, was said to have cured lepers.

María de Guadalupe appeared for the first time in the preserved record in 1733 as the daughter of Antonia Martín and Miguel de Agüero. The next year, Antonia de Medina and Juan Luiz Martines named their daughter María de Guadalupe.

The name next was used in 1738 for Marta de Guadalupe Trujillo and in 1739 for Rosa María de Guadalupe Archuleta. After that, María Guadalupe was used twice in the mid-1740s and five times in the 1750s.

Between the baptism of the Agüero daughter and the christening of the Trujillo girl, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe was transformed in México from a miracle worker into one who reversed the course of mysterious diseases. Simultaneously, she was transformed from a cult particular to Natives into a symbol shared by all people born in Nueva España. Of the eleven girls named for her in Santa Cruz, only three were Indians, probably Apache or Comanche. The rest had two known parents.

As discussed in the post for 24 February 2016, an infection began spreading through México in 1736. No one knew what matlazáhuatl was. They could only react with procedures that worked with other epidemics like the smallpox contagion of 1733. The viceroy, Juan de Vizarrón provided food and hospitals. Robert McCaa said, he funded four doctors and six pharmacists.

The city council opted for public prayers and asked the viceroy, who was also the archbishop, to lead a novena for the Virgin of Loreto in early January of 1737. When that failed, they asked to have Nuestra Señora de los Remedios brought to the cathedral for nine more days of prayers led by Bartolomé de Ita y Para.

That too failed to stem the disease that was killing more Indians than Spaniards. Rumors were spreading. Stafford Poole said, "a sick woman in delirium saw the fever in the form of a woman on the causeway to Guadalupe." Another told of an Indian woman shouting in the sanctuary at Tepeyac, "let the Spanish die also." Stories were repeated of Indians dumping corpses into aqueducts and mixing victims’ blood in bread dough.

Members of the city’s council suggested bringing the painting of Guadalupe to the city cathedral; others objected the agave fabric was too fragile. Instead, Vizarrón suggested a pilgrimage there for a Novena. Again Ita y Parra spoke.

Still no relief. A comet was seen, probably at the end of January. In February the council agreed to swear an oath of fealty to Guadalupe, with April 27 set for the ceremony. A partial eclipse of the sun occurred March 1, beginning just after noon and lasting 90 minutes. The oath was made public after a procession and mass on May 26. By chance or divine intervention, the epidemic finally began to recede.

The intensity of veneration that followed was not chance. David Brading suggested, it became the vehicle for Mexican-born criollo clergymen to assert their independence from Spanish superiors sent by the Bourbon king.

Ita y Parra, the man who preached the "The Mother of Health sermon" at Tepeyac in 1737, was a Puebla-born Jesuit. He was explicating a new founding legend couched in Old Testament symbols when he asserted Los Remedios failed to stop the epidemic because she was from Spain, a Ruth forever homeless. Guadalupe, on the other hand, would prevail because she was, like Naomi, a native.

Matlazáhuatl arrived in Zacatecas in 1737 during a grain shortage. The city stockpiled grain and called upon its one hospital, two charitable brotherhoods, and private doctors. The Franciscans took the image of Guadalupe to all the churches in mass processions that probably spread the air-born pathogen.

Within the church, men lobbied for Guadalupe’s elevation to patroness for all Nueva España, distinct from Santiago of Spain. In 1746, delegates from city councils and cathedral chapters gathered to acclaim her patronato. Benedict XIV approved their actions in 1754.

Meanwhile, Francisco de Echávarri began supervising construction of an aqueduct to take water to the shine in Tepeyac in 1741. He had been a mine inspector. This was an extension of the civil engineering then being introduced to drain mines. The water main was completed in 1751, after the end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1748.

Guadalupe bound the criollos to the Indians against the Spaniards. Once the villa of Tepeyac had its basic necessity supplied, a college of canons was established to officiate at the shrine. To be appointed, one had to speak a native language.

Notes: Marta was probably meant to be María; her last name was written Truxillo.

Comets were still unexpected phenomena, not yet explained by science. In México, Augustinian Matías de Escobar wrote it was "a phenomenon notoriously caused by the exhalations of the seas and the corrupt humours of the body," while at Cambridge Isaac Newton suspected it might appear in 1737 based on orbits of previous comets, but wouldn’t commit himself to friends or to print. It was sighted in 1737 in Jamaica on January 26, in Philadelphia on January 27, and in Lisbon on January 29. Ignatius Kegler, a Jesuit missionary for whom it was named, observed it in Beijing on July 3.

Brading, D. A. Church and State in Bourbon Mexico, 1994.

_____. Mexican Phoenix, 2002.

Brodbeck, Roland. "Solar eclipses, Mexico, Coatzacoalcos, 1700 - 2100," 1998, in cooperation with the Swiss Astronomical Society.

Escobar, Matías de. Voces de Tritón Sonora, 1746; quoted by Brading, 1994.

Ita y Para, Bartolomé de "The Mother of Health," paraphrased by Brading, 2002.

Kronk, Gary W. Cometography, volume 1, 1999.

Lynn, W. T. "The Comet of A. D. 1737," The Observatory, May 1901.

McCaa, Robert. "Revisioning Smallpox in Mexico City-Tenochtitlán, 1520-1950," 27 May 2000.

New Mexico Genealogical Society, New Mexico Baptisms, Santa Cruz de la Cañada Church, Volume I, 1710 to 1794, transcribed by Virginia Langham Olmstead and compiled by Margaret Leonard Windham and Evelyn Luján Baca, 1994. Notes in the records varied, so they couldn’t be used to identify the ethnicity of the baptized. I’m assuming if both parents were known the parents were Españoles; if only the mother’s names were known the child was illegitimate and probably Español but possibly meztiso or captive; if no parents were known I’m assuming the baptized were captives.

Newton, Isaac. Comment on comet quoted by William Whiston and reported by Lynn; elaborated by Kronk.

Poole, Stafford. Our Lady of Guadalupe, 1995.

Raigoza Quiñónez, José Luis. "Factores de Influencia para la Transmisión y Difusión del Matlazáhuatl en Zacatecas 1737-38," Scripta Nova, August 2006.

Sunday, May 15, 2016

Baptismal Names

Baptismal names in this period reflected a conviction the rite brought an infant under the church’s protection. The majority of the names used in both Nuevo México and New England had biblical origins, but the local ones were drawn from oral tradition while the others came from the Bible itself.

One element of the Reformation rejected by the Roman Catholic church was making translations of Bibles in vernacular languages available to parishioners. In Spain, owning a Bible was used as evidence a person was Jewish. The Inquisition made even references to the Jewish Old Testament suspect.

Between 1733 and 1759, 50% of the 1909 children baptized in Santa Cruz had New Testament names, but only less than 1% came for the older section. In one of my grandparent’s families living in Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine in those years, 62% of the 149 children had names taken from the Old Testament and 28% from the new.

* = .15%

In Santa Cruz, the two Benitos alluded to Benjamin, founder of one of the twelve tribes of Israel in Genesis. The one Susana had a name that appeared in Daniel. In contrast, in New England where the Bible was readily available, names came primarily from Genesis, Kings, Chronicles, and Samuel.

The most common New Testament name in both areas came from the four Gospels. In Santa Cruz, there were 305 girls baptized with María as a first or second name. In my family, 11 were called Mary. One wonders, with nearly a third of the 948 girls given the same name, what they were called informally to differentiate them. One of the New England Marys was known as Molly.

Juan, after one of the apostles, was the second most common name for boys in Santa Cruz, and also used as Juana for girls. Joseph was the third most popular male name. Josepha was the female counterpart. José didn’t appear. John was given to five boys in New England. I suspect the six named Joseph were for the patriarch sold into slavery in Genesis.

Many of the other New Testament names used in Santa Cruz appeared in all four gospels. However Juan and Santiago did not appear in John and Joana was found only in Luke. Manuel from Emmanuel and Juan Baptista came from Matthew, the book most famously consulted by Francis of Assisi.

The local names that came from other books of the New Testament were Pablo and Paula from Acts, and Manuel, Manuela, Miguel and variants of Michaela from Revelations. In New England, Acts and Timothy were the other sources.

While English Calvinists drew their views on the human condition from the unpredictable Yahweh of the Old Testament, Spanish Catholics were given the church as exemplar for lives dedicated to perpetuating its patrimony. The lives of saints in the Flos Sanctorum was the accepted source for information about both Him and his guardians.

Anna and Joachin or Joachina, the names of Mary’s parents, came from that source, as did another 87 names used in Santa Cruz. The most popular were Lorenzo/Lorenza, Nicholas/Nicolosa, Patricio, and Dorotea. As discussed in the post for 24 April 2016, the English translation of Golden Legend also was widely read. My family named girls Anna, Lucia, and Dorothy.

Most of the remaining names used in Santa Cruz, some 47% came from saints and church fathers. Children were symbolically dedicated to the continuation of the institution. Franciscan fathers Antonio and Francisco ranked first and fourth among male names, and second and tenth among female. Ignacio and Ignacia acknowledged the progenitor of the Jesuits, and Gertrudis the champion of the Sacred Heart. Luis, with the female Luisa, was patron of the secular third order of the Franciscans.

Some of the saints recognized in Santa Cruz were unique to Spain. Many editions of Flos Sanctorum had been expanded with biographies of local heroes and heroines. The most common in Santa Cruz were Ramon or Reymundo, Quiteria, and Visente. Ones beatified in the New World included Aparicio, Beltran and Toribio. The names of mystics were only given to girls: the Benedictine Lugarda, the Augustinian Rita, and the Carmelite Teresa of Ávala.

One other naming habit shared by parents in both Santa Cruz and New England was the use of Christian virtues. Here they applied attributes to María and named girls Angela, Ascension or Prudencia. Boys were called Atanacio, literally meaning without death, and Ynociencio. My family used Mercy and Patience.

Female names without sources appear in the list of male names

Notes:

Santa Cruz data from New Mexico Genealogical Society, New Mexico Baptisms, Santa Cruz de la Cañada Church, Volume I, 1710 to 1794, transcribed by Virginia Langham Olmstead and compiled by Margaret Leonard Windham and Evelyn Luján Baca, 1994.

The sacramental register has a number of missing pages, so the total is an undercount. The total also does not include Spanish-speakers living near San Juan or Santa Clara who baptized their children in one of those missions. Those omissions would have affected the demographic statistics, but probably wouldn’t have altered conclusions regarding naming patterns.

My grandparent’s immigrant ancestor William and his wife arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony before 1637 with their four children, William, Thomas, Sarah, and John. Their great-grandchildren, the fourth generation, born between 1733 and 1760 were the ones used for the statistics for comparative New England naming patterns.

The family’s only atypical characteristic was that William was not a Puritan. His children, who had common English names, adopted Calvinist ones for their children, the third generation, and most probably affiliated with the church.

Quotations from Jonathan Edwards in the post for 24 April 2016 gives an idea of the Puritan concept of God.

The Flos Sanctorum, or Golden Legend, was discussed in the post for 1 May 2016.

One element of the Reformation rejected by the Roman Catholic church was making translations of Bibles in vernacular languages available to parishioners. In Spain, owning a Bible was used as evidence a person was Jewish. The Inquisition made even references to the Jewish Old Testament suspect.

Between 1733 and 1759, 50% of the 1909 children baptized in Santa Cruz had New Testament names, but only less than 1% came for the older section. In one of my grandparent’s families living in Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine in those years, 62% of the 149 children had names taken from the Old Testament and 28% from the new.

| Source | Santa Cruz | New England |

| Old Testament | * | 62% |

| New Testament | 50% | 28% |

| Founder | 24% | |

| Healer | 8% | |

| Golden Legend | 7% | 3% |

| Mystic | 3% | |

| Spanish Saint | 2% | |

| Attribute | 1% | 1% |

| Other Saint | 3% | |

| Other | 2% | 6% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

In Santa Cruz, the two Benitos alluded to Benjamin, founder of one of the twelve tribes of Israel in Genesis. The one Susana had a name that appeared in Daniel. In contrast, in New England where the Bible was readily available, names came primarily from Genesis, Kings, Chronicles, and Samuel.

The most common New Testament name in both areas came from the four Gospels. In Santa Cruz, there were 305 girls baptized with María as a first or second name. In my family, 11 were called Mary. One wonders, with nearly a third of the 948 girls given the same name, what they were called informally to differentiate them. One of the New England Marys was known as Molly.

Juan, after one of the apostles, was the second most common name for boys in Santa Cruz, and also used as Juana for girls. Joseph was the third most popular male name. Josepha was the female counterpart. José didn’t appear. John was given to five boys in New England. I suspect the six named Joseph were for the patriarch sold into slavery in Genesis.

Many of the other New Testament names used in Santa Cruz appeared in all four gospels. However Juan and Santiago did not appear in John and Joana was found only in Luke. Manuel from Emmanuel and Juan Baptista came from Matthew, the book most famously consulted by Francis of Assisi.

The local names that came from other books of the New Testament were Pablo and Paula from Acts, and Manuel, Manuela, Miguel and variants of Michaela from Revelations. In New England, Acts and Timothy were the other sources.

While English Calvinists drew their views on the human condition from the unpredictable Yahweh of the Old Testament, Spanish Catholics were given the church as exemplar for lives dedicated to perpetuating its patrimony. The lives of saints in the Flos Sanctorum was the accepted source for information about both Him and his guardians.

Anna and Joachin or Joachina, the names of Mary’s parents, came from that source, as did another 87 names used in Santa Cruz. The most popular were Lorenzo/Lorenza, Nicholas/Nicolosa, Patricio, and Dorotea. As discussed in the post for 24 April 2016, the English translation of Golden Legend also was widely read. My family named girls Anna, Lucia, and Dorothy.

Most of the remaining names used in Santa Cruz, some 47% came from saints and church fathers. Children were symbolically dedicated to the continuation of the institution. Franciscan fathers Antonio and Francisco ranked first and fourth among male names, and second and tenth among female. Ignacio and Ignacia acknowledged the progenitor of the Jesuits, and Gertrudis the champion of the Sacred Heart. Luis, with the female Luisa, was patron of the secular third order of the Franciscans.

Some of the saints recognized in Santa Cruz were unique to Spain. Many editions of Flos Sanctorum had been expanded with biographies of local heroes and heroines. The most common in Santa Cruz were Ramon or Reymundo, Quiteria, and Visente. Ones beatified in the New World included Aparicio, Beltran and Toribio. The names of mystics were only given to girls: the Benedictine Lugarda, the Augustinian Rita, and the Carmelite Teresa of Ávala.

One other naming habit shared by parents in both Santa Cruz and New England was the use of Christian virtues. Here they applied attributes to María and named girls Angela, Ascension or Prudencia. Boys were called Atanacio, literally meaning without death, and Ynociencio. My family used Mercy and Patience.

| Girls' Names | Number | Source |

| Maria | 305 | NT - mother of Jesus |

| Antonia | 99 | Founder - Franciscans |

| Joana | 41 | NT Luke - healed by Christ |

| Manuela | 37 | |

| Juana | 34 | |

| Barbara | 32 | Holy helper |

| Josepha | 32 | |

| Anna | 23 | James - mother of Mary |

| Gertrudis | 22 | Mystic - Sacred Heart |

| Francisca | 19 | |

| Rosa/Rosalia | 33 | Healer |

| Teresa | 15 | Spanish mystic |

| Margarita | 14 | Holy helper |

| Isabel | 13 | Founder - Poor Clares |

| Micaela/Micalina/Mica | 15 | |

| Juliana | 12 | |

| Ignacia | 11 | |

| Lugarda | 11 | Mystic - Benedictine |

| Luisa | 10 | |

| Rita | 10 | Mystic - Augustinian |

| Boys' Names | ||

| Antonio | 179 | Founder - Franciscans |

| Juan | 129 | NT - apostle |

| Joseph | 115 | NT - father of Jesus |

| Francisco | 44 | Founder - Franciscans |

| Manuel | 37 | NT Matthew |

| Miguel | 34 | NT Revelations |

| Cristobal | 25 | Healer |

| Pedro | 25 | NT - apostle |

| Domingo | 20 | Founder - Domincans |

| Julian | 18 | Healer |

| Felipe | 17 | NT - apostle |

| Santiago | 17 | NT - apostle |

| Salvador | 15 | NT - attribute of Christ |

| Ignacio | 14 | Founder - Jesuits |

| Luis | 11 | Founder - Franciscans |

| Pablo | 11 | NT Acts - apostle |

| Andres | 10 | NT - apostle |

| Gregorio | 10 | Other - pope |

| Joachin | 10 | James - father of Mary |

| Juan Bapitsta | 10 | NT Matthew - baptized Christ |

Female names without sources appear in the list of male names

Notes:

Santa Cruz data from New Mexico Genealogical Society, New Mexico Baptisms, Santa Cruz de la Cañada Church, Volume I, 1710 to 1794, transcribed by Virginia Langham Olmstead and compiled by Margaret Leonard Windham and Evelyn Luján Baca, 1994.

The sacramental register has a number of missing pages, so the total is an undercount. The total also does not include Spanish-speakers living near San Juan or Santa Clara who baptized their children in one of those missions. Those omissions would have affected the demographic statistics, but probably wouldn’t have altered conclusions regarding naming patterns.

My grandparent’s immigrant ancestor William and his wife arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony before 1637 with their four children, William, Thomas, Sarah, and John. Their great-grandchildren, the fourth generation, born between 1733 and 1760 were the ones used for the statistics for comparative New England naming patterns.

The family’s only atypical characteristic was that William was not a Puritan. His children, who had common English names, adopted Calvinist ones for their children, the third generation, and most probably affiliated with the church.

Quotations from Jonathan Edwards in the post for 24 April 2016 gives an idea of the Puritan concept of God.

The Flos Sanctorum, or Golden Legend, was discussed in the post for 1 May 2016.

Sunday, May 08, 2016

The Sacraments

The Council of Trent defined acceptance of the sacraments as "necessary for every individual" and, by implication, defined their administration as the primary responsibility of the clergy. It labeled the Protestant view that "men obtain of God, through faith alone, the grace of justification" as "anathema."

The Council proclaimed the "seven sacraments are in such wise equal to each other," but that was not the operative view of them in Nuevo México. Baptism was the most widely accepted because even little children who "have not actual faith" were "reckoned amongst the faithful."

It was so important laymen were allowed to perform the rite with "true and natural water" in emergencies. This occurred five times in Santa Cruz between 1733 and 1759. Phelipe Romero baptized Juana Naranjo in 1739, Antonio Bernal blessed Juana Luiza Martín in 1745, and Julian Madrid committed Gervacio Duran in 1753. In 1753 Joanna Archuleta was baptized by necessity, as was Juan Domingo in 1758.

The fact the rite defined one as a member of the church’s community was seen as a form of protection against the Inquisition, which still existed as a threat. While the Council denied the act freed men from "the observance of the whole law of Christ," people seemed to think having their children baptized as they had been was sufficient evidence of their sanctity.

Men had the captives they purchased from the Comanche baptized. The friars argued this step alone made it impossible for Natives to return to their bands. The men who recruited their godparents instead may have wanted validation of the purchase and justification for the subsequent presence of hitherto unknown unmarried young men and women in their households.

The idea of baptism as protection was absorbed by the Jicarilla Apache, who were willing to submit to it in exchange for military support. That may have been the view of the Navajo who listened to Carlos Delgado and José de Irigoyen, but then rejected the corollary expectation they moved into pueblos.

The pueblos clearly saw baptism as an attempt to interfere with their traditional ways. In 1760, thirty years after Juan Miguel Menchero had decreed sacraments were to be administered for free to Natives, Juan Sanz protested any suggestion friars expected compensation. He wrote:

"In baptizing the children, it is necessary for the father to ascertain carefully when they are born, for if he does not, they do not bring children to be baptized, and if they had to pay an obvention, would they ever be baptized?"

The rite of matrimony probably was more accepted by those with property, since it and wills were the instruments that ensured the orderly transfer of assets from generation to generation. Others may have avoided the sacrament to elude interference by friars into their lives. The diligencias matrimoniales not only cost money but enforced prohibitions against certain kinds of marriages between kin not related by blood, like that between a man and his dead wife’s sister. Dispensations were possible, but added delays and notary fees.

The pueblos were more resistant because friars saw it as their duty to impose western concepts of family. Sanz noted, "if it is for obliging them to marry, this is done when they are discovered in concubinage, which is an invariable custom among them."

Carlos Delgado’s comments, quoted in the post for 24 February 2016, that friars had to travel at all hours suggested the more faithful accepted the need for "Extreme Unction." It was the only duty that required a priest to leave the precincts of the church.

The sacrament was merged with two others in these years, penance and the Eucharist, into the belief people needed to attend mass once a year, and to attend mass they had to confess once a year. This was clearly the doctrinal point behind Benito Crespo’s complaints discussed in the post for 3 April 2016 that many missions in Nuevo México did not meet this minimum.

Actual burial practices were rarely recorded. Angélico Chávez noted the burial registers didn’t begin until 1726 at Santa Cruz, Santa Clara and San Juan del Caballeros. The cover of the one used at Santa Cruz until 1768 was "limp tan leather." The flyleaf was "decorated with heavy scroll border, skulls, skeletons."

Deposition of bodies apparently was a private matter. In 1744, Menchero noted at Rancho del Embudo, where there were constant attacks by indios bárbaros, "The whole place is full of crosses." In 1776, Francisco Domínguez noted La Soledad, the settlement founded by Sebastían Martín north of San Juan, had "a little cemetery."

The pueblos treated death as a another aspect of their lives they wanted sheltered from clerical oversight. Sanz was correct when he observed people living in the pueblos "would die without confession and the father would not know about it," but probably misled when he thought "they would carry the body off to a ravine in order to avoid obvention."

Confirmations were rare. The Council of Trent had explicitly stated the sacrament could only be performed by a bishop. In 1760, Pedro Tamarón recorded he confirmed 96 at Embudo and that "they were prepared for it, and they recited the catechism." He did not mention performing the sacrament at either of the two local pueblos or La Cañada.

The seventh sacrament, the ordination of priests, was not practiced locally. This was the one the Council had in mind when it said "all (the sacraments) are not necessary for every individual."

Notes: On mission to Navajo, see post for 10 April 2016. I don’t know whether either group of Athabascan speakers saw some other value in having "water thrown upon" their heads. I haven’t found any comments of their beliefs prior to their contact with French and Spanish missionaries. Fees were discussed in the post for 27 March 2016. The use of skeletons and skulls as decorative motifs was mentioned in the post for 10 April 2016.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Chávez, Angélico. Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900, 1957.

Council of Trent. "On the Sacraments, First Decree and Canons," 3 March 1547. I’m quoting this since some things were changed by the Second Vatican Council held between 1962 and 1965. Some sacraments, especially penance, later acquired additional significance in northern New Mexico.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez in The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Menchero, Juan Miguel. Declaration, 10 May 1744, Santa Bárbara; translation in Bandelier.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 Novmber1760; translation in Bandelier. [Esp Hist I17] p475

Tamarón y Romeral, Pedro. The Kingdom of New Mexico, 1760, translation in Eleanor B. Adams, Bishop Tamarón’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760, 1954.

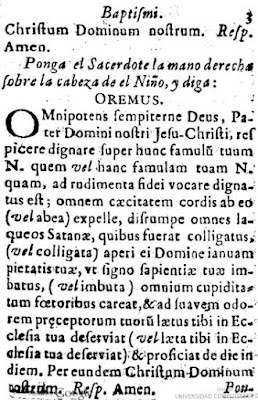

Graphics: First page on baptisms from Agustín de Vetancurt, Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, 1729 edition, discussed in the post for 1 May 2016.

The Council proclaimed the "seven sacraments are in such wise equal to each other," but that was not the operative view of them in Nuevo México. Baptism was the most widely accepted because even little children who "have not actual faith" were "reckoned amongst the faithful."

It was so important laymen were allowed to perform the rite with "true and natural water" in emergencies. This occurred five times in Santa Cruz between 1733 and 1759. Phelipe Romero baptized Juana Naranjo in 1739, Antonio Bernal blessed Juana Luiza Martín in 1745, and Julian Madrid committed Gervacio Duran in 1753. In 1753 Joanna Archuleta was baptized by necessity, as was Juan Domingo in 1758.

The fact the rite defined one as a member of the church’s community was seen as a form of protection against the Inquisition, which still existed as a threat. While the Council denied the act freed men from "the observance of the whole law of Christ," people seemed to think having their children baptized as they had been was sufficient evidence of their sanctity.

Men had the captives they purchased from the Comanche baptized. The friars argued this step alone made it impossible for Natives to return to their bands. The men who recruited their godparents instead may have wanted validation of the purchase and justification for the subsequent presence of hitherto unknown unmarried young men and women in their households.

The idea of baptism as protection was absorbed by the Jicarilla Apache, who were willing to submit to it in exchange for military support. That may have been the view of the Navajo who listened to Carlos Delgado and José de Irigoyen, but then rejected the corollary expectation they moved into pueblos.

The pueblos clearly saw baptism as an attempt to interfere with their traditional ways. In 1760, thirty years after Juan Miguel Menchero had decreed sacraments were to be administered for free to Natives, Juan Sanz protested any suggestion friars expected compensation. He wrote:

"In baptizing the children, it is necessary for the father to ascertain carefully when they are born, for if he does not, they do not bring children to be baptized, and if they had to pay an obvention, would they ever be baptized?"

The rite of matrimony probably was more accepted by those with property, since it and wills were the instruments that ensured the orderly transfer of assets from generation to generation. Others may have avoided the sacrament to elude interference by friars into their lives. The diligencias matrimoniales not only cost money but enforced prohibitions against certain kinds of marriages between kin not related by blood, like that between a man and his dead wife’s sister. Dispensations were possible, but added delays and notary fees.

The pueblos were more resistant because friars saw it as their duty to impose western concepts of family. Sanz noted, "if it is for obliging them to marry, this is done when they are discovered in concubinage, which is an invariable custom among them."

Carlos Delgado’s comments, quoted in the post for 24 February 2016, that friars had to travel at all hours suggested the more faithful accepted the need for "Extreme Unction." It was the only duty that required a priest to leave the precincts of the church.

The sacrament was merged with two others in these years, penance and the Eucharist, into the belief people needed to attend mass once a year, and to attend mass they had to confess once a year. This was clearly the doctrinal point behind Benito Crespo’s complaints discussed in the post for 3 April 2016 that many missions in Nuevo México did not meet this minimum.

Actual burial practices were rarely recorded. Angélico Chávez noted the burial registers didn’t begin until 1726 at Santa Cruz, Santa Clara and San Juan del Caballeros. The cover of the one used at Santa Cruz until 1768 was "limp tan leather." The flyleaf was "decorated with heavy scroll border, skulls, skeletons."

Deposition of bodies apparently was a private matter. In 1744, Menchero noted at Rancho del Embudo, where there were constant attacks by indios bárbaros, "The whole place is full of crosses." In 1776, Francisco Domínguez noted La Soledad, the settlement founded by Sebastían Martín north of San Juan, had "a little cemetery."

The pueblos treated death as a another aspect of their lives they wanted sheltered from clerical oversight. Sanz was correct when he observed people living in the pueblos "would die without confession and the father would not know about it," but probably misled when he thought "they would carry the body off to a ravine in order to avoid obvention."

Confirmations were rare. The Council of Trent had explicitly stated the sacrament could only be performed by a bishop. In 1760, Pedro Tamarón recorded he confirmed 96 at Embudo and that "they were prepared for it, and they recited the catechism." He did not mention performing the sacrament at either of the two local pueblos or La Cañada.

The seventh sacrament, the ordination of priests, was not practiced locally. This was the one the Council had in mind when it said "all (the sacraments) are not necessary for every individual."

Notes: On mission to Navajo, see post for 10 April 2016. I don’t know whether either group of Athabascan speakers saw some other value in having "water thrown upon" their heads. I haven’t found any comments of their beliefs prior to their contact with French and Spanish missionaries. Fees were discussed in the post for 27 March 2016. The use of skeletons and skulls as decorative motifs was mentioned in the post for 10 April 2016.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Chávez, Angélico. Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900, 1957.

Council of Trent. "On the Sacraments, First Decree and Canons," 3 March 1547. I’m quoting this since some things were changed by the Second Vatican Council held between 1962 and 1965. Some sacraments, especially penance, later acquired additional significance in northern New Mexico.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez in The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Menchero, Juan Miguel. Declaration, 10 May 1744, Santa Bárbara; translation in Bandelier.

Sanz de Lezaún, Juan. An account of lamentable happenings in New Mexico and of losses experienced daily in affairs spiritual and temporal, 4 Novmber1760; translation in Bandelier. [Esp Hist I17] p475

Tamarón y Romeral, Pedro. The Kingdom of New Mexico, 1760, translation in Eleanor B. Adams, Bishop Tamarón’s Visitation of New Mexico, 1760, 1954.

Graphics: First page on baptisms from Agustín de Vetancurt, Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, 1729 edition, discussed in the post for 1 May 2016.

Sunday, May 01, 2016

Franciscan Traditions

Franciscan friars were literate men. They maintained sacramental books, kept accounts, and read letters circulated by their superiors. More important, they knew how to use the missals and manuals found by Francisco Domínguez in the churches of Santa Cruz, San Juan del Caballeros, and Santa Clara in 1776. They could decipher both Latin and Castilian.

One guide to administering the sacraments Domínguez saw in the Santa Cruz sacristy would have been in use in these years. The collection of Latin scripts, first published in Mexico City in 1674 by Agustín de Vetancurt, wasn’t superceded until 1748. The Franciscan editor was born in Puebla, worked with Nahuatl speakers, then wrote histories.

The first page of his Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos featured a woodcut of Santo Joseph with a dedication to him as guardian.

Joseph is mentioned as the husband of Mary in the Gospel of Matthew, which was the book that inspired Francis of Assisi to exchange earthly goods for poverty. Sometime around the year 145, the Gospel of James appeared. It described Joseph’s selection by the temple as the guardian of the adolescent Mary, in a tale reminiscent of Cinderella. All unmarried men of the House of David were ordered to bring their rods to the temple, where a sign from the Lord would identify the chosen man. It read:

"Joseph took his rod last; and, behold, a dove came out of the rod, and flew upon Joseph's head."

The book by Joseph’s son circulated in Greek manuscripts, but apparently not in Latin. In the early 600s the Gospel of Saint Matthew appeared in Latin, supposedly in a translation by Jerome. It elaborated on James.

"But as soon as he stretched forth his hand, and laid hold of his rod, immediately from the top of it came forth a dove whiter than snow, beautiful exceedingly, which, after long flying about the roofs of the temple, at length flew towards the heavens."

This gospel circulated widely. Brandon Hawke noted it moved into Anglo-Saxon tradition from the Carolingians in France. In 1260, an Italian Dominican, Jacobus de Voragine, included Saint Matthew’s story of Joseph in his Legenda Aurea. More than a thousand copies survive in manuscript. William Caxton published the Golden Legend in English in 1483. Alexander Wilkinson found a Castilian Flos Sanctorum published in the 1470s, a Catalan one from Barcelona in 1495, and Le Leyendo de los Santos from Burgos in 1499.

Voragine both simplified Matthew’s version, and embellished it:

"then Joseph by the commandment of the bishop brought forth his rod, and anon it flowered, and a dove descended from heaven thereupon."

The Council of Trent discouraged the interest in the legends of saints to promote factual biographies. Voragine’s text was republished in revisions by Alonso de Villegas in 1578 and by the Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneyra in 1599.

However, it’s the earlier image the Spanish shared with Caxton of the flowering rod that greeted the friars in Santa Cruz each time they opened the manual to read the baptismal language.

Notes: This James, better known as James the Just, was not the same disciple as James the Great, better known as Santiago. James the Just described Joseph as an elderly widow, which would have made himself the step-brother of Jesus.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez, The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Hawk, Brandon W. "Preaching the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew in Anglo-Saxon England," York Christian Apocrypha Symposium, 2015.

James. Gospel, translated by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Matthew. Gospel, translation by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Roberts, Alexander, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Ante-Nicene Fathers, volume 8, 1886; revised and edited by Kevin Knight.

Vetancurt, Agustín de. Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, first published 1674; woodcut from 1729 edition.

Voragine, Jacobus de. Legenda Aurea, translated by William Caxton, 1483; edited by F. S. Ellis, 1900.

Wikipedia. Primary source for history of the apocryphal gospels.

Wilkinson, Alexander S. Iberian Books, 2010.

One guide to administering the sacraments Domínguez saw in the Santa Cruz sacristy would have been in use in these years. The collection of Latin scripts, first published in Mexico City in 1674 by Agustín de Vetancurt, wasn’t superceded until 1748. The Franciscan editor was born in Puebla, worked with Nahuatl speakers, then wrote histories.

The first page of his Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos featured a woodcut of Santo Joseph with a dedication to him as guardian.

Joseph is mentioned as the husband of Mary in the Gospel of Matthew, which was the book that inspired Francis of Assisi to exchange earthly goods for poverty. Sometime around the year 145, the Gospel of James appeared. It described Joseph’s selection by the temple as the guardian of the adolescent Mary, in a tale reminiscent of Cinderella. All unmarried men of the House of David were ordered to bring their rods to the temple, where a sign from the Lord would identify the chosen man. It read:

"Joseph took his rod last; and, behold, a dove came out of the rod, and flew upon Joseph's head."

The book by Joseph’s son circulated in Greek manuscripts, but apparently not in Latin. In the early 600s the Gospel of Saint Matthew appeared in Latin, supposedly in a translation by Jerome. It elaborated on James.

"But as soon as he stretched forth his hand, and laid hold of his rod, immediately from the top of it came forth a dove whiter than snow, beautiful exceedingly, which, after long flying about the roofs of the temple, at length flew towards the heavens."

This gospel circulated widely. Brandon Hawke noted it moved into Anglo-Saxon tradition from the Carolingians in France. In 1260, an Italian Dominican, Jacobus de Voragine, included Saint Matthew’s story of Joseph in his Legenda Aurea. More than a thousand copies survive in manuscript. William Caxton published the Golden Legend in English in 1483. Alexander Wilkinson found a Castilian Flos Sanctorum published in the 1470s, a Catalan one from Barcelona in 1495, and Le Leyendo de los Santos from Burgos in 1499.

Voragine both simplified Matthew’s version, and embellished it:

"then Joseph by the commandment of the bishop brought forth his rod, and anon it flowered, and a dove descended from heaven thereupon."

The Council of Trent discouraged the interest in the legends of saints to promote factual biographies. Voragine’s text was republished in revisions by Alonso de Villegas in 1578 and by the Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneyra in 1599.

However, it’s the earlier image the Spanish shared with Caxton of the flowering rod that greeted the friars in Santa Cruz each time they opened the manual to read the baptismal language.

Notes: This James, better known as James the Just, was not the same disciple as James the Great, better known as Santiago. James the Just described Joseph as an elderly widow, which would have made himself the step-brother of Jesus.

Domínguez, Francisco Atanasio. Manuscript report, 1776, translated and annotated by Eleanor B. Adams and Angélico Chávez, The Missions of New Mexico, 1776, 1956.

Hawk, Brandon W. "Preaching the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew in Anglo-Saxon England," York Christian Apocrypha Symposium, 2015.

James. Gospel, translated by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Matthew. Gospel, translation by Alexander Walker in Roberts.

Roberts, Alexander, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Ante-Nicene Fathers, volume 8, 1886; revised and edited by Kevin Knight.

Vetancurt, Agustín de. Manual de Administratrar los Santos Sacramentos, first published 1674; woodcut from 1729 edition.

Voragine, Jacobus de. Legenda Aurea, translated by William Caxton, 1483; edited by F. S. Ellis, 1900.

Wikipedia. Primary source for history of the apocryphal gospels.

Wilkinson, Alexander S. Iberian Books, 2010.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)