Comanche destroyed all evidence a dead person ever existed. Women loudly mourned for a year, while relatives gave away or destroyed his or her property. They never spoke the name again, lest it revive painful memories. If he was a chief, the band changed its name.

These customs left no oral history from the late 1600s when the group was metamorphosing from Great Basin foragers into plains warriors. Their neighbors didn’t remember them, because their naming patterns provided no mnemonics.

Comanche spoke a Shoshone language, and must have been part of the groups who moved into arid areas of Nevada and Utah after the Colorado Plateau was abandoned by pueblo dwellers in the late 1200s.

In the 1930s, western Shoshone remembered lives measured by seasons of plants. In early spring, they ate new shoots, often raw. As soon as seeds began ripening on grasses, they began moving to elevations where crops could be eaten. Women gathered seeds in baskets, and either threw hot rocks into the baskets to roast them or ground them on a metate.

In summer berries became available, then later roots. They supplemented their diet with small animals and insects, rodents, lizards, snakes, grasshoppers and cicadas.

Family groups, usually with six members, moved from place to place, sometimes meeting others, sometimes alone. Come fall, they moved higher to harvest piñon nuts. Groups converged, but in mast years, there were more than enough nuts for everyone. They had two weeks to pick enough to last the winter. The ones they didn’t eat immediately, they buried where they would winter near water and firewood.

Great Basin piñon only produces good crops every two to three years, depending on oscillations in the polar front jet stream. If animals were plentiful, men organized communal hunts. They would drive rabbits into nets, clubbing enough to eat. They would drive pronghorn into brush corrals. They weren’t able to store the meat, and if they killed too many, they couldn’t hunt again for several years. Life was precarious in winter.

By 1500, some bands of Shoshone had crossed the Rocky Mountains and others were in the Green River basin. Eventually, eastern bands moved through South Pass of Wyoming onto the plains. The lives they led must have been close to those remembered a few years ago by Ute. Shoshone-speaking Ute elders remembered they always moved north along the mountains in spring and summer following the ripening seeds, roots, and insects.

In fall they moved onto the plains where men hunted deer. Women remained in the higher lands where they harvested piñon. By the nineteenth century, they kew how to dry meat and make parfleche.

When winter approached they entered New Mexico where they camped in sheltered meadows near Cimarron, Taos, or Abiquiu. There they passed on their lore. It was considered bad luck to tell tales in summer.

As winter waned, Utes moved north, still following the sun in a clockwise manner. When they reached the area of Conejos, they held their Bear Dance. They believed they were descended from bears, and were obligated to help them waken from hibernation. It was at this time, relatives of the dead destroyed property.

When Julian Steward asked about significance of a woman keening at a 1931 dance, his queries brought bland denials that spirits of the dead returned during the festival.

Like the Shoshone, the Ute held communal hunts. And, like them, they appointed leaders who organized rabbit hunts. The position wasn’t permanent. The men selected to manage pronghorn hunts were shamans who could charm animals into the snares. They had no powers beyond the hunt. Similarly, the ones who directed Bear Dances were only responsible for those eventss.

Shoshone had no large-scale gatherings like the Bear Dance. Their natural resources wouldn’t have support a large group for a week. Even the Ute, in the past, held more, smaller, shorter festivals than the few held today on reservation lands.

Neither Ute nor Shoshone developed any social structure beyond the nuclear family. Groups were bound by marriages. Their was no food sharing, but solitary relatives like grandparents, aunts, and uncles were brought into family units. Isolated adolescent boys were adopted through a second marriage to the wife of the nuclear group. Brothers and sisters of adults also were given security through polygamy and polyandry. Even then, traveling groups rarely exceeded ten members.

Few disputes before 1700 escalated into open conflict. Shoshone had no sense of exclusive territory; whoever arrived in a food area first had rights. They named areas for the food they produced. Steward thinks the current names for clans came from outsiders misunderstanding this sense of property. For the Ute and Shoshone whoever was visiting an area that grew yampa was a yampa eater; when they left, and another moved in they became the yampa eaters. The term was not a permanent appellation for a group, but a more important way to remember the geography of plants.

Families settled feuds among themselves. When attacked by outsiders, they preferred escape than fighting. The exception occurred when someone, perhaps an evil shaman, was believed to be responsible for the death of a family member. Then, revenge was condoned.

Notes: Studies of contemporary groups don’t reveal what existed in the past. They do document what evolved from what might have been common custom. Steward doesn’t think the family-based lives of the Shoshone were the foundation of future societies; instead they represented an adaption away from traditional band structure that was driven by limited food resources.

Yampa, Perideridia gairdneri, is a member of the parsley family. Wikipedia says the roots are "crunchy and mildly sweet, and resemble in texture and flavor water chestnuts."

Campbell, G. "Ute Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography," in An Ethnological and Ethnohistorical Assessment of Ethnobotanical and Cultural Resources at the Sand Creek National Historic Site and Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site, 2007.

Neilson, Ronald P. "On the Interface between Current Ecological Studies and the Paleobotany of Pinyon-juniper Woodlands," Pinyon-Juniper Conference, Proceedings, 1986. The Great Basin species is Pinus monophylla. The one that grows on the Colorado Plateau, Pinus edulis, has a good nut crop every five years. It’s affected by summer monsoons and the sub-tropical jet stream that oscillates every three to five years.

Reed, Verner Z. "Ute Bear Dance," American Anthropologist 9:237-244:1896.

Steward, Julian H. Basin-Plateau Sociopolitical Groups, 1938.

_____. "The Great Basin Shoshonean Indians: An Example of a Family Level of Sociocultural Integration," in Theory of Culture Change, 1955; source for comment in notes.

_____. "The Uintah Ute Bear Dance," American Anthropologist 34:263-273:1932.

Wallace, Ernest and E. Adamson Hoebel. The Comanches, 1986 edition.

Tuesday, June 30, 2015

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Bourbon Reviews

Perhaps the most obvious change in Bourbon management of Nuevo México flowed from its objective view of reality. Decisions no longer depended on faith in individuals. Reports were examined for factual integrity. The viceroy took advantage of safer travel to send investigators to verify what he was sent.

The first was the juez de residencia sent to sift through the opposing charges made by Juan Flores Mogollón and Félix Martínez in 1721. Little is known about Juan Estrada de Austria, who also served as interim governor. I suspect an early historian confused Austria with Asturias and the mistake has hindered research ever since.

An invisitador general followed Estrada in 1722. Antonio Cobián Busto found the presidio poorly defended and evidence of illegal trade with Louisiana.

The military was next to initiate a fact finding tour. Pedro de Rivera Villalón visited 23 garrisoned towns between 1724 and 1728. He was particularly critical of graft that inflated the cost of defense. In 1726 he noted Juan Bustamante had increased the number of positions in the garrison that drew from the treasury. He believed twenty could be cut.

Rivera also found governors and capitanes overcharged soldiers for their equipment. If fixed

prices were established, he believed salaries could be cut by 10% and soldiers would still have more money.

The fourth investigation was conducted by the bishop of Durango in 1730. Benito Crespo y Monroy criticized local Franciscans. There were 30 positions, but only 24 were filled. He found the priests didn’t bother to learn native languages, didn’t administer sacraments, and didn’t collect or expend tithes properly.

Among those he accused of neglect were Juan de la Cruz of San Juan and Manuel Sopeña of Santa Clara. The governors of those two pueblos weren’t among the ones listed as speaking Castilian in 1706 by Francisco Cuervo. Of those from San Juan called in the Leonor Domínguez trial in 1708, Catarina Rosa, Catarina Luján and Juan understood Castilian, Angelina Pumazjo did not.

Language had become a political issue. Philip V realized a government wasn’t effective if it couldn’t communicate with its people. In 1713, he commissioned the Real Academia Española to standardize the Castilian language much like the Académie Française had done in France in 1635.

Successful alliances with Native Americans had become a matter of realpolitiks. The French Jesuits were considered more successful than the Franciscans because their priests became fluent in native languages. Franciscans had responded to criticisms in 1683 with the Santa Cruz missionary college at Querétaro to train friars. However, John Kessell says, it began as a haven for Spanish retirees, especially from Majorca.

Settlers had learned to exploit the status quo. When Cobián asked why the area was so unsettled, they said the bárbaros were dangerous, there weren’t enough settlers, and poverty was great. They meant, send us more soldiers, settlers, and free supplies.

They protested the cuts Rivera proposed because that extra money ended in the pockets of merchants and creditors. No doubt some were the ones buying those purloined horses.

The response to Crespo was conditioned by individual contacts with pueblos. Sebastían Martín, Alonso Rael de Aguilar, and Antonio de Ulibarrí needed them to supply auxiliaries. Since that was a role pueblos accepted, they were friendly and may have conducted negotiations in Castilian.

The men who criticized the friars were ones who had administrative responsibilities. Pueblo members were probably suspicious of them, and unwilling to engage in Castilian. Critic Diego de Torres was the teniente de alcalde mayor of Santa Clara. Juan Páez Hurtado was the one who took over the governorship in 1716 when Valverde was recalled to Mexico City.

The only man from Santa Cruz who supported the friars because he was close to them was Tomás Núñez de Haro.

Notes:

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Kessell, John L. Spain in the Southwest, 2002.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, collected by Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, included in Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

The first was the juez de residencia sent to sift through the opposing charges made by Juan Flores Mogollón and Félix Martínez in 1721. Little is known about Juan Estrada de Austria, who also served as interim governor. I suspect an early historian confused Austria with Asturias and the mistake has hindered research ever since.

An invisitador general followed Estrada in 1722. Antonio Cobián Busto found the presidio poorly defended and evidence of illegal trade with Louisiana.

The military was next to initiate a fact finding tour. Pedro de Rivera Villalón visited 23 garrisoned towns between 1724 and 1728. He was particularly critical of graft that inflated the cost of defense. In 1726 he noted Juan Bustamante had increased the number of positions in the garrison that drew from the treasury. He believed twenty could be cut.

Rivera also found governors and capitanes overcharged soldiers for their equipment. If fixed

prices were established, he believed salaries could be cut by 10% and soldiers would still have more money.

The fourth investigation was conducted by the bishop of Durango in 1730. Benito Crespo y Monroy criticized local Franciscans. There were 30 positions, but only 24 were filled. He found the priests didn’t bother to learn native languages, didn’t administer sacraments, and didn’t collect or expend tithes properly.

Among those he accused of neglect were Juan de la Cruz of San Juan and Manuel Sopeña of Santa Clara. The governors of those two pueblos weren’t among the ones listed as speaking Castilian in 1706 by Francisco Cuervo. Of those from San Juan called in the Leonor Domínguez trial in 1708, Catarina Rosa, Catarina Luján and Juan understood Castilian, Angelina Pumazjo did not.

Language had become a political issue. Philip V realized a government wasn’t effective if it couldn’t communicate with its people. In 1713, he commissioned the Real Academia Española to standardize the Castilian language much like the Académie Française had done in France in 1635.

Successful alliances with Native Americans had become a matter of realpolitiks. The French Jesuits were considered more successful than the Franciscans because their priests became fluent in native languages. Franciscans had responded to criticisms in 1683 with the Santa Cruz missionary college at Querétaro to train friars. However, John Kessell says, it began as a haven for Spanish retirees, especially from Majorca.

Settlers had learned to exploit the status quo. When Cobián asked why the area was so unsettled, they said the bárbaros were dangerous, there weren’t enough settlers, and poverty was great. They meant, send us more soldiers, settlers, and free supplies.

They protested the cuts Rivera proposed because that extra money ended in the pockets of merchants and creditors. No doubt some were the ones buying those purloined horses.

The response to Crespo was conditioned by individual contacts with pueblos. Sebastían Martín, Alonso Rael de Aguilar, and Antonio de Ulibarrí needed them to supply auxiliaries. Since that was a role pueblos accepted, they were friendly and may have conducted negotiations in Castilian.

The men who criticized the friars were ones who had administrative responsibilities. Pueblo members were probably suspicious of them, and unwilling to engage in Castilian. Critic Diego de Torres was the teniente de alcalde mayor of Santa Clara. Juan Páez Hurtado was the one who took over the governorship in 1716 when Valverde was recalled to Mexico City.

The only man from Santa Cruz who supported the friars because he was close to them was Tomás Núñez de Haro.

Notes:

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Kessell, John L. Spain in the Southwest, 2002.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, collected by Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, included in Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

Thursday, June 25, 2015

Bourbon Reforms

Philip V inherited a Spanish civil service enfeebled by predecessors who used payments from sales of positions to finance their wars. The men he chose as viceroys in Mexico City were men he’d learned to trust during the War of Spanish Succession. Baltasar de Zúñiga y Guzman had been viceroy of Sardinia between 1704 and 1707, Juan de Acuña had been governor of Messina in Sicily between 1701 and 1713.

Since the rein of Philip II, the monarchy had looked for ways to share benefits that accrued to men in its service. Notaries were the first group required to pay for the privilege of charging set fees for filing government paperwork. When few were willing to bid, Philip made them permanent positions that could be resold in 1581, so long as the crown received a third of the value and the buyers were competent. Santa Cruz friars didn’t maintain their own notaries, but used public ones for diligencias matrimoniales.

In 1606, Philip III expanded the right of resale to members of cabildos with no competency requirement. As many have observed, accurate paperwork was important to the Hapsburgs, but they didn’t want local governments to be have independent powers.

Judicial offices were not sellable, until Charles II began using a subterfuge in the 1670s. John Parry said, there’s no record of governorship sales for Nuevo México before the Revolt. Philip ended the practice in 1713. José Chacón was the last governor appointed under the old system.

While Philip tried to reform his administration, he couldn’t solve the underlying problem that plagued it. There wasn’t enough money to pay adequate salaries. Men at every level were forced to augment their income.

Nuevo México was too poor for simple embezzlement by its governors in these years. Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón was found guilt of malfeasance. Félix Martínez de Torrelaguna sold Ute slaves, but was removed over irregularities in presidio accounts. Antonio Valverde y Cosío established large land holdings near El Paso del Norte that he worked with Apache slaves captured during his military campaigns. His nephew and son-in-law, Juan Domingo de Bustamante, was found guilty of illegal trade.

The men appointed as governors were sometimes men who had spent years in the colonial bureaucracy. Flores had come from Seville. His previous assignment was the governorship of Nuevo León y Coahuila. Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora, the man who replaced Bustamante, was the grandson of a Philippine governor. He began his career working for the bishop de Durango.

Philip didn’t attempt to reorganize the Spanish military until 1717. Then he limited his changes to Havana. Presidio soldiers were still paid as they had been when enlisted men were expected to support themselves from spoils of war. Valverde had to issue orders in 1718 prohibiting soldiers from selling horses from the royal herd.

He was a Cantabrian businessman who migrated to oversee his interests. De Vargas recruited him and Martínez in Zacatecas. The latter was from Valencia.

Notes: Sales of lesser offices continued until 1812. Governorships were occasionally sold later to support war efforts, according to Eissa-Barroso, but the practice was rare and short-lived each time.

Chartrand, Rene. The Spanish Army in North America 1700-1793, 2011.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Eissa-Barroso, Francisco A. "‘Having Served in the Troops’: The Appointment of Military Officers as Provincial Governors in Early Eighteenth-Century Spanish America, 1700-1746," Colonial Latin American Historical Review 1:329-359:2013.

Parry, J. H. The Sale of Public Office in the Spanish Indies under the Hapsburgs, 1953.

Valverde y Cosío, Antonio. Order, 17 July 1718, described in Frederic J. Athearn, A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978.

Since the rein of Philip II, the monarchy had looked for ways to share benefits that accrued to men in its service. Notaries were the first group required to pay for the privilege of charging set fees for filing government paperwork. When few were willing to bid, Philip made them permanent positions that could be resold in 1581, so long as the crown received a third of the value and the buyers were competent. Santa Cruz friars didn’t maintain their own notaries, but used public ones for diligencias matrimoniales.

In 1606, Philip III expanded the right of resale to members of cabildos with no competency requirement. As many have observed, accurate paperwork was important to the Hapsburgs, but they didn’t want local governments to be have independent powers.

Judicial offices were not sellable, until Charles II began using a subterfuge in the 1670s. John Parry said, there’s no record of governorship sales for Nuevo México before the Revolt. Philip ended the practice in 1713. José Chacón was the last governor appointed under the old system.

While Philip tried to reform his administration, he couldn’t solve the underlying problem that plagued it. There wasn’t enough money to pay adequate salaries. Men at every level were forced to augment their income.

Nuevo México was too poor for simple embezzlement by its governors in these years. Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón was found guilt of malfeasance. Félix Martínez de Torrelaguna sold Ute slaves, but was removed over irregularities in presidio accounts. Antonio Valverde y Cosío established large land holdings near El Paso del Norte that he worked with Apache slaves captured during his military campaigns. His nephew and son-in-law, Juan Domingo de Bustamante, was found guilty of illegal trade.

The men appointed as governors were sometimes men who had spent years in the colonial bureaucracy. Flores had come from Seville. His previous assignment was the governorship of Nuevo León y Coahuila. Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora, the man who replaced Bustamante, was the grandson of a Philippine governor. He began his career working for the bishop de Durango.

Philip didn’t attempt to reorganize the Spanish military until 1717. Then he limited his changes to Havana. Presidio soldiers were still paid as they had been when enlisted men were expected to support themselves from spoils of war. Valverde had to issue orders in 1718 prohibiting soldiers from selling horses from the royal herd.

He was a Cantabrian businessman who migrated to oversee his interests. De Vargas recruited him and Martínez in Zacatecas. The latter was from Valencia.

Notes: Sales of lesser offices continued until 1812. Governorships were occasionally sold later to support war efforts, according to Eissa-Barroso, but the practice was rare and short-lived each time.

Chartrand, Rene. The Spanish Army in North America 1700-1793, 2011.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Eissa-Barroso, Francisco A. "‘Having Served in the Troops’: The Appointment of Military Officers as Provincial Governors in Early Eighteenth-Century Spanish America, 1700-1746," Colonial Latin American Historical Review 1:329-359:2013.

Parry, J. H. The Sale of Public Office in the Spanish Indies under the Hapsburgs, 1953.

Valverde y Cosío, Antonio. Order, 17 July 1718, described in Frederic J. Athearn, A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978.

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Communications

México’s economic role as supplier of European currency waned when silver production declined under Charles II. At same time, the English in the Caribbean began growing sugar cane.

The calculus of shipping, trade and wealth was altered. During the boom, Spain had sent one fleet a year to México to pick up silver and leave provisions. By the end of the 1600s, departures were less predictable because there was no profit in an empty return load.

Meantime, Dutch ships were servicing the sugar colonies. When the number of export trips increased, so did the number of goods imported into the islands. The English responded by passing laws to monopolize shipping to its colonies. French colonies planted sugar cane. Carolina traders turned southeastern Native Americans into a Caribbean labor resource. Madrid worried about its king’s likely successor.

When communication with México slowed, so did the ability of Madrid to manage its Empire. In 1718, the new Spanish king, Philip V, tried to remedy the problem by ordering mail ships leave for the Indies four times a year. Men with the mail contract resisted, because they still saw no profits.

Communication within the kingdom of New Spain improved some. There were more mining towns along the camino real so the distance to the interior through hostile territory was shorter. El Paso del Norte had become a mission. Natives in its immediate area were less likely to attack.

Conditions still weren’t ideal. Nothing had changed the currents and winds that took two to three months to move sailing ships across the Atlantic. Even so, in 1724, the governor of Nuevo México was notified about the king’s January abdication before 23 September. If the news left with the late March aviso, and took three months to cross, it reached Veracruz in late June. Three months from there to Santa Fé, eight months total.

Of course, by the time the governor issued his proclamation, the new king was dead from smallpox. It took longer for the news of Philip’s reascension to reach the colony: ten months.

Inland communication within Native American groups was quicker, but often second hand. Every band knew white men were trading guns for slaves, but few were sure of differences between the French and English.

Information sent by bands to the governor had to be treated with the same caution as news that arrived in Mexico City from English or French ships in the Caribbean. Both may have been more timely, but motives needed to be evaluated. Plains bands gave the French false information to prevent them from meeting with their enemies. Jicarilla may have exaggerated threats to get protection from the Spanish. Valverde exaggerated the French threat to get more help from Mexico City.

Notes: For more on development of sugarcane, see the posts under Barbados at right.

Kuethe, Allan J. and Kenneth J. Andrien. The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century, 2014.

Lamikiz, Xabier. Trade and Trust in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, 2013.

Marx, Robert F. Shipwrecks in the Americas, 1987.

Pearce, Adrian J. The Origins of Bourbon Reform in Spanish South America, 1700-1763, 2014.

The calculus of shipping, trade and wealth was altered. During the boom, Spain had sent one fleet a year to México to pick up silver and leave provisions. By the end of the 1600s, departures were less predictable because there was no profit in an empty return load.

Meantime, Dutch ships were servicing the sugar colonies. When the number of export trips increased, so did the number of goods imported into the islands. The English responded by passing laws to monopolize shipping to its colonies. French colonies planted sugar cane. Carolina traders turned southeastern Native Americans into a Caribbean labor resource. Madrid worried about its king’s likely successor.

When communication with México slowed, so did the ability of Madrid to manage its Empire. In 1718, the new Spanish king, Philip V, tried to remedy the problem by ordering mail ships leave for the Indies four times a year. Men with the mail contract resisted, because they still saw no profits.

Communication within the kingdom of New Spain improved some. There were more mining towns along the camino real so the distance to the interior through hostile territory was shorter. El Paso del Norte had become a mission. Natives in its immediate area were less likely to attack.

Conditions still weren’t ideal. Nothing had changed the currents and winds that took two to three months to move sailing ships across the Atlantic. Even so, in 1724, the governor of Nuevo México was notified about the king’s January abdication before 23 September. If the news left with the late March aviso, and took three months to cross, it reached Veracruz in late June. Three months from there to Santa Fé, eight months total.

Of course, by the time the governor issued his proclamation, the new king was dead from smallpox. It took longer for the news of Philip’s reascension to reach the colony: ten months.

Inland communication within Native American groups was quicker, but often second hand. Every band knew white men were trading guns for slaves, but few were sure of differences between the French and English.

Information sent by bands to the governor had to be treated with the same caution as news that arrived in Mexico City from English or French ships in the Caribbean. Both may have been more timely, but motives needed to be evaluated. Plains bands gave the French false information to prevent them from meeting with their enemies. Jicarilla may have exaggerated threats to get protection from the Spanish. Valverde exaggerated the French threat to get more help from Mexico City.

Notes: For more on development of sugarcane, see the posts under Barbados at right.

Kuethe, Allan J. and Kenneth J. Andrien. The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century, 2014.

Lamikiz, Xabier. Trade and Trust in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, 2013.

Marx, Robert F. Shipwrecks in the Americas, 1987.

Pearce, Adrian J. The Origins of Bourbon Reform in Spanish South America, 1700-1763, 2014.

Sunday, June 21, 2015

Franco-Spanish Relations

Soon after the end of the War of Spanish Successions, the king of France died in 1715. Louis XIV left a five-year-old dauphin. The regent, Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans, sought peace with his neighbors to protect the throne. When Philip V, king of Spain, made aggressive moves to recover his lost territories on the Italian peninsula, war broke out between France and Spain in 1718.

The French sent Claude-Charles du Tisne west along tributaries of the Missouri to locate the Wichita and Apache in 1719. He traveled through a poisoned atmosphere. Each group he met suspected he might be a slave trader. Once convinced he was friendly, they were unwilling to help him go farther west lest he arm their enemies with guns. He got as far west as the Wichita who refused to let him pass.

Coincidentally, the Comanche joined the Utes attacking the northern pueblos and Spanish settlements. They penetrated as far south as Embudo during the dry summer of 1719. When the governor, Antonio Valverde, called his military leaders, most wanted to attack. Only a few living in the north like Sebastían Martín and Ignacio de Roybal y Torrado advised caution.

Valverde lead a force of 60 soldiers from the presidio, 45 settlers, 465 warriors from the pueblos and 165 Apache out onto the plains. When they got to El Cuartelejo, they found men with gunshot wounds. The plains Apache told them the Panana and Jumano had been armed by the French. The governor returned to Santa Fé with greatly exaggerate reports of threats on the eastern frontier.

Meantime, war had ended in Europe with the Treaty of the Hague, signed in February of 1720. Before he had word of the changed situation, Valverde sent Pedro de Villasur to locate the Pawnees in June with 42 men from the presidio, 3 settlers, and 60 auxiliaries. One August morning as they were breaking camp, they were ambushed. Eleven of the pueblo troops were killed with 31 of the soldiers. They represented nearly a third of the garrison forces. The viceroy saw it as a truce violation by Spain.

France and Spain signed a friendship treaty in 1721. When Britain joined the alliance, it was given trade concessions in the Spanish colonies. Peace lasted until Louis XV came of age in 1723 and the Duc d’Orléans died. Distrust returned. Spain banned all trade with the French in Louisiana.

In 1724, Philip V abdicated in favor of his son. Historians have debated since if it was another ploy to unseat Louis XV or if he feared he was becoming mentally unstable.

Another French trader, Bourgmont, traveled west with Osage and Missouris into Kansas to develop relations with the Padouca. When the viceroy sent his own man to investigate the situation, he was told the Comanche were powerful, but the fight should be left to the Apache. Relations between France and Spain were too unsettled to sanction war.

Philip’s son died in August, and Philip returned to the throne. France broke the marriage contracts that had accompanied the treaty of 1721. Spain realigned itself with the Hapsburgs. Competition between France and Spain reopened in Texas.

Notes: Sieur de Bourgmont was Étienne de Veniard. Pananas were Pawnee. Bourgmont thought the Padouca were Comanche. Grinnell decided they were the Apache who later became the Kiowa Apache. Villasur’s survivors thought their attackers were Pawnee.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Grinnell, George B. "Who Were the Padouca?", American Anthropologist 22:248-260:1920.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Thomas, Alfred B. After Coronado, 1935.

The French sent Claude-Charles du Tisne west along tributaries of the Missouri to locate the Wichita and Apache in 1719. He traveled through a poisoned atmosphere. Each group he met suspected he might be a slave trader. Once convinced he was friendly, they were unwilling to help him go farther west lest he arm their enemies with guns. He got as far west as the Wichita who refused to let him pass.

Coincidentally, the Comanche joined the Utes attacking the northern pueblos and Spanish settlements. They penetrated as far south as Embudo during the dry summer of 1719. When the governor, Antonio Valverde, called his military leaders, most wanted to attack. Only a few living in the north like Sebastían Martín and Ignacio de Roybal y Torrado advised caution.

Valverde lead a force of 60 soldiers from the presidio, 45 settlers, 465 warriors from the pueblos and 165 Apache out onto the plains. When they got to El Cuartelejo, they found men with gunshot wounds. The plains Apache told them the Panana and Jumano had been armed by the French. The governor returned to Santa Fé with greatly exaggerate reports of threats on the eastern frontier.

Meantime, war had ended in Europe with the Treaty of the Hague, signed in February of 1720. Before he had word of the changed situation, Valverde sent Pedro de Villasur to locate the Pawnees in June with 42 men from the presidio, 3 settlers, and 60 auxiliaries. One August morning as they were breaking camp, they were ambushed. Eleven of the pueblo troops were killed with 31 of the soldiers. They represented nearly a third of the garrison forces. The viceroy saw it as a truce violation by Spain.

France and Spain signed a friendship treaty in 1721. When Britain joined the alliance, it was given trade concessions in the Spanish colonies. Peace lasted until Louis XV came of age in 1723 and the Duc d’Orléans died. Distrust returned. Spain banned all trade with the French in Louisiana.

In 1724, Philip V abdicated in favor of his son. Historians have debated since if it was another ploy to unseat Louis XV or if he feared he was becoming mentally unstable.

Another French trader, Bourgmont, traveled west with Osage and Missouris into Kansas to develop relations with the Padouca. When the viceroy sent his own man to investigate the situation, he was told the Comanche were powerful, but the fight should be left to the Apache. Relations between France and Spain were too unsettled to sanction war.

Philip’s son died in August, and Philip returned to the throne. France broke the marriage contracts that had accompanied the treaty of 1721. Spain realigned itself with the Hapsburgs. Competition between France and Spain reopened in Texas.

Notes: Sieur de Bourgmont was Étienne de Veniard. Pananas were Pawnee. Bourgmont thought the Padouca were Comanche. Grinnell decided they were the Apache who later became the Kiowa Apache. Villasur’s survivors thought their attackers were Pawnee.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Grinnell, George B. "Who Were the Padouca?", American Anthropologist 22:248-260:1920.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Thomas, Alfred B. After Coronado, 1935.

Thursday, June 18, 2015

1714-1732

Santa Cruz Leaders

Red are the monarchs of Spain

Bold are the viceroys of New Spain

Regular type are the governors of New Mexico

Alcaldes and notaries in Santa Cruz are listed at the bottom; not enough information exists to establish their tenures

Bourbon Dynasty. Continues to 1724. Philip V

Continues to 1714 War of Spanish Succession

1718-1720 War of the Quadruple Alliance

Continues to 1716. Fernando de Alencastre Noroña y Silva, Duque de Linares

Continues to 1712. Jose Chacón Medina Salazar y Villaseñor

1712-1715. Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón

1715-1716, acting. Félix Martínez de Torrelaguna

1716, acting. Antonio Valverde y Cosío

1716-1722. Baltasar de Zúñiga y Guzman, Marques de Valero y Duque de Arion

1716-1717, acting. Juan Páez Hurtado

1718-1721, interim. Antonio Valverde y Cosío

1721-. Juan Estrada de Austria [Asturias?]

1722-. Juan de Acuña, Marques de Casa Fuerte

Continues to 1723. Juan Estrada de Austria [Asturias?]

1723-. Juan Domingo de Bustamante

Bourbon Dynasty, 1724-1724. Louis I

Continues. Juan Domingo de Bustamante

Bourbon Dynasty, 1724-. Philip V

Continues to 1731. Juan Domingo de Bustamante

1731-. Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora

Men Mentioned as Alcaldes in Santa Cruz

1714 Sebastían Martín Serrano

1716 Juan García de la Rivas

Tomás López Holguín

1718 Francisco José Bueno de Bohórques y Corcuera

1720 Francisco José Bueno de Bohórques y Corcuera

Cristóbal Torres

1724 Cristóbal Torres

Francisco José Bueno de Bohórques y Corcuera

1729 Miguel José de la Vega

Notaries

1714-1725 Miguel de Quintana

1722-1730 José de Atienza y Alcalá

1728-1730 José Bernardo Gómez

1718 Francisco Afán de Ribera Betanzos

Ignacio de Roybal

Francisco Monte Vigil

1719 José de Atienza y Alcalá

1727 Simón Martín

Note:

Viceroys from Wallace L. McKeehan, "Viceroys, Commandantes, Governors & Presidents," DeWitt Colony, Texas website.

Monarchs and governors from Wikipedia.

Red are the monarchs of Spain

Bold are the viceroys of New Spain

Regular type are the governors of New Mexico

Alcaldes and notaries in Santa Cruz are listed at the bottom; not enough information exists to establish their tenures

Bourbon Dynasty. Continues to 1724. Philip V

Continues to 1714 War of Spanish Succession

1718-1720 War of the Quadruple Alliance

Continues to 1716. Fernando de Alencastre Noroña y Silva, Duque de Linares

Continues to 1712. Jose Chacón Medina Salazar y Villaseñor

1712-1715. Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón

1715-1716, acting. Félix Martínez de Torrelaguna

1716, acting. Antonio Valverde y Cosío

1716-1722. Baltasar de Zúñiga y Guzman, Marques de Valero y Duque de Arion

1716-1717, acting. Juan Páez Hurtado

1718-1721, interim. Antonio Valverde y Cosío

1721-. Juan Estrada de Austria [Asturias?]

1722-. Juan de Acuña, Marques de Casa Fuerte

Continues to 1723. Juan Estrada de Austria [Asturias?]

1723-. Juan Domingo de Bustamante

Bourbon Dynasty, 1724-1724. Louis I

Continues. Juan Domingo de Bustamante

Bourbon Dynasty, 1724-. Philip V

Continues to 1731. Juan Domingo de Bustamante

1731-. Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora

Men Mentioned as Alcaldes in Santa Cruz

1714 Sebastían Martín Serrano

1716 Juan García de la Rivas

Tomás López Holguín

1718 Francisco José Bueno de Bohórques y Corcuera

1720 Francisco José Bueno de Bohórques y Corcuera

Cristóbal Torres

1724 Cristóbal Torres

Francisco José Bueno de Bohórques y Corcuera

1729 Miguel José de la Vega

Notaries

1714-1725 Miguel de Quintana

1722-1730 José de Atienza y Alcalá

1728-1730 José Bernardo Gómez

1718 Francisco Afán de Ribera Betanzos

Ignacio de Roybal

Francisco Monte Vigil

1719 José de Atienza y Alcalá

1727 Simón Martín

Note:

Viceroys from Wallace L. McKeehan, "Viceroys, Commandantes, Governors & Presidents," DeWitt Colony, Texas website.

Monarchs and governors from Wikipedia.

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

Spain’s Acheulean Technology

Cultures, technologies and species follow similar evolutionary tracks. Each creates many variants at its center. Every individual moving toward the periphery takes one version. Thus, the center can be identified by its greater diversity, which also tends to reinforce it ability to innovate. The outer edges lag behind, until some event stimulates them into becoming centers of creativity.

1.6 million years ago, even before hominins in Spain were adapting Oldowan technology to Iberian rocks, others in the East African Rift Valley were making Acheulean tools: the oval bi-faced axes, picks, and cleavers commonly associated with the old stone age.

Sediments at Konso, in southwestern Ethiopia, indicate the area was then a drying lake bed. The mammals that migrated there included grass-eating cloven-hoofed bovids like antelope, and a number of pig-like animals. These replaced endemic species that had lived there when the area was wetter.

Like the Oldowan, Acheulean tool makers used locally available basalt. Yonas Beyene’s team believed picks originated when Homo erectus was emerging. They speculated the heavy tools were used to handle wood or to dig.

Once perfected, pick manufacturing did not change. Hand axes, however, began as thick blades about 1.6 million years ago. With practice, the shapes became more symmetrical and the edges near the tip were thinned. In another 400,000 years, the shapes were developing "three-dimensional symmetry." The team thinks the changes in spatial judgement reflected increased cognitive abilities honed by changing requirements for butchering skills.

The centrifugal movement of ideas and species from a core area may occur when groups move into empty areas. If, instead, they meet other groups, the expansion of a technology may occur when one displaces the other, when one trades with the other, or when the two interbreed.

Acheulean technology reached Europe by 500,000 years ago, during the warmer period following the Günz Glacier, and was in the Atapuerca area 100,000 years later, just before the advance of the Mindel glacier. The limestone formation was now riddled with caves. The Gran Dolina and Galería are part of the northern Trinchera del Ferrocarri, the Sima del Elefante part of the southern Cueva Mayor. Sima de los Huesos is connected to the last.

Hand axes and cleavers found at Galería were made from quartzite from local river terraces. Most were small and showed signs of having been used to cut animal tissue. Ones with more abrupt edges were used to scrape hides. A few showed signs of use on wood.

A single lower jaw bone found there has been associated with Homo heidelbergensis. Although the stone workers knew the area well, the cave was not used to make tools. Eudald Carbonell and Paula García-Medrano thought they entered the caves when they believed an animal had become trapped. They dismembered it, and took the pieces elsewhere to eat.

Among the animal bones found in the cave were those of giant, fallow and red deer, and large goats. There were also some rhinoceros, bison, and horse remains. The most common predators, who came after the hominins left, were red foxes, wildcats, and hyenas.

Less than a mile and a half away, Sima de los Huesos was a more treacherous trap. An opening near the top dropped some 43' to the floor. Archaeologists found remains of more than 150 Deninger’s bears, some in every layer. They even found bears’ nests and claw marks where they tried to escape. Ursus deningeri is believed to be the ancestor of cave bears.

Underneath the bears, they found remains of 28 Homo heidelbergensis. There were nine adolescents, nine young adults, five mature adults, and four over thirty divided between eight males and eleven females. All the skeletal parts survived, even ear bones.

Carbonell and Juan Luis Arsuaga both think it was a deliberate burial of corpses because the bones for individuals weren’t widely scattered. The most important piece of evidence was a hand axe made from a particularly attractive piece of quartzite. It’s the only tool in the cave. Aging has made it impossible to know if it was ever used, or was completely symbolic.

Carbonell noted studies of the mid-ear bone suggested these hominins had developed the physical capacity for language. Recently, Svante Pääbo’s team tested the mitochondrial DNA from one femur, expecting to find connections between it and the Neanderthals that followed. Instead, the group found evidence of Denisova hominins, a species found later in the Altai mountains of Siberia.

Speciation within the Homo genus has turned out to be more complex than expected for isolated populations living on frontiers where the males must have mated outside the group. Mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the female side.

Notes: Research teams rotate credit for articles between members. I’ve grouped them by the director or lead member; the articles often are found under the name of the second person listed.

Arsuaga, J. L., et alia. "Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). The Site," Journal of Human Evolution 33:109-127:1997.

Beyene, Yonas, et alia. "The Characteristics and Chronology of the Earliest Acheulean at Konso, Ethiopia," National Academy of Science, Proceedings 110:1584-1591:2013.

_____, Shinji Nagaoka, et alia. "Lithostratigraphy and Sedimentary Environments of the Hominid-Bearing Pliocene-Pleistocene Konso Formation in the Southern Main Ethiopian Rift, Ethiopia," Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 216:333-357:2005.

_____, Gen Suwa, et alia. "Plio-pleistocene Terrestrial Mammal Assemblage from Konso, Southern Ethiopia," Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23:901-916:2003. The animals included:

Antelope - Damaliscus niro

Pig - Metridiochoerus compactus, Metridiochoerus hopwoodi, Metridiochoerus modestus and Kolpochoerus limnetes/olduvaiensis

Carbonell, Eudald, Paula García-Medrano, et alia. "The Earliest Acheulean Technology at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain): Oldest Levels of the Galería Site (Gii Unit)," Quaternary International 353:170-194:2014. Animals included:

Giant deer - Megaloceros solilhacus sspp

Fallow deer - Dama dama clactoniana

Red deer - Cervus elaphus priscus

Goat - Hemitragus bonali

Bison - Bison sp. (small),

Rhinoceros - Stephanorhinus cf. hemitoechus

Horse - Equus ferus, Equus cf. hydruntinus

Carnivores

Red fox - Vulpes vulpes

Wildcat - Felis sylvestris

_____ and Marina Mosquera. The Emergence of a Symbolic Behaviour: the Sepulchral Pit of Sima De Los Huesos, Sierra De Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain," Comptes Rendus Palevol 5:155-160:2006.

Pääbo, Svante, Matthias Meyer, et alia. "A Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of a Hominin from Sima De Los Huesos," Nature 505:403-406:2014.

Graphics:

1. NordNordWest. "Location Map of Konso, Ethiopia," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 11 September 2009.

2. Benito, José-Manuel. " Plan of La Trinchera del Ferrocarril, in the Archaeological Site of Atapuerca (Spain)," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, October 2002.

1.6 million years ago, even before hominins in Spain were adapting Oldowan technology to Iberian rocks, others in the East African Rift Valley were making Acheulean tools: the oval bi-faced axes, picks, and cleavers commonly associated with the old stone age.

Sediments at Konso, in southwestern Ethiopia, indicate the area was then a drying lake bed. The mammals that migrated there included grass-eating cloven-hoofed bovids like antelope, and a number of pig-like animals. These replaced endemic species that had lived there when the area was wetter.

Like the Oldowan, Acheulean tool makers used locally available basalt. Yonas Beyene’s team believed picks originated when Homo erectus was emerging. They speculated the heavy tools were used to handle wood or to dig.

Once perfected, pick manufacturing did not change. Hand axes, however, began as thick blades about 1.6 million years ago. With practice, the shapes became more symmetrical and the edges near the tip were thinned. In another 400,000 years, the shapes were developing "three-dimensional symmetry." The team thinks the changes in spatial judgement reflected increased cognitive abilities honed by changing requirements for butchering skills.

The centrifugal movement of ideas and species from a core area may occur when groups move into empty areas. If, instead, they meet other groups, the expansion of a technology may occur when one displaces the other, when one trades with the other, or when the two interbreed.

Acheulean technology reached Europe by 500,000 years ago, during the warmer period following the Günz Glacier, and was in the Atapuerca area 100,000 years later, just before the advance of the Mindel glacier. The limestone formation was now riddled with caves. The Gran Dolina and Galería are part of the northern Trinchera del Ferrocarri, the Sima del Elefante part of the southern Cueva Mayor. Sima de los Huesos is connected to the last.

Hand axes and cleavers found at Galería were made from quartzite from local river terraces. Most were small and showed signs of having been used to cut animal tissue. Ones with more abrupt edges were used to scrape hides. A few showed signs of use on wood.

A single lower jaw bone found there has been associated with Homo heidelbergensis. Although the stone workers knew the area well, the cave was not used to make tools. Eudald Carbonell and Paula García-Medrano thought they entered the caves when they believed an animal had become trapped. They dismembered it, and took the pieces elsewhere to eat.

Among the animal bones found in the cave were those of giant, fallow and red deer, and large goats. There were also some rhinoceros, bison, and horse remains. The most common predators, who came after the hominins left, were red foxes, wildcats, and hyenas.

Less than a mile and a half away, Sima de los Huesos was a more treacherous trap. An opening near the top dropped some 43' to the floor. Archaeologists found remains of more than 150 Deninger’s bears, some in every layer. They even found bears’ nests and claw marks where they tried to escape. Ursus deningeri is believed to be the ancestor of cave bears.

Underneath the bears, they found remains of 28 Homo heidelbergensis. There were nine adolescents, nine young adults, five mature adults, and four over thirty divided between eight males and eleven females. All the skeletal parts survived, even ear bones.

Carbonell and Juan Luis Arsuaga both think it was a deliberate burial of corpses because the bones for individuals weren’t widely scattered. The most important piece of evidence was a hand axe made from a particularly attractive piece of quartzite. It’s the only tool in the cave. Aging has made it impossible to know if it was ever used, or was completely symbolic.

Carbonell noted studies of the mid-ear bone suggested these hominins had developed the physical capacity for language. Recently, Svante Pääbo’s team tested the mitochondrial DNA from one femur, expecting to find connections between it and the Neanderthals that followed. Instead, the group found evidence of Denisova hominins, a species found later in the Altai mountains of Siberia.

Speciation within the Homo genus has turned out to be more complex than expected for isolated populations living on frontiers where the males must have mated outside the group. Mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the female side.

Notes: Research teams rotate credit for articles between members. I’ve grouped them by the director or lead member; the articles often are found under the name of the second person listed.

Arsuaga, J. L., et alia. "Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). The Site," Journal of Human Evolution 33:109-127:1997.

Beyene, Yonas, et alia. "The Characteristics and Chronology of the Earliest Acheulean at Konso, Ethiopia," National Academy of Science, Proceedings 110:1584-1591:2013.

_____, Shinji Nagaoka, et alia. "Lithostratigraphy and Sedimentary Environments of the Hominid-Bearing Pliocene-Pleistocene Konso Formation in the Southern Main Ethiopian Rift, Ethiopia," Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 216:333-357:2005.

_____, Gen Suwa, et alia. "Plio-pleistocene Terrestrial Mammal Assemblage from Konso, Southern Ethiopia," Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23:901-916:2003. The animals included:

Antelope - Damaliscus niro

Pig - Metridiochoerus compactus, Metridiochoerus hopwoodi, Metridiochoerus modestus and Kolpochoerus limnetes/olduvaiensis

Carbonell, Eudald, Paula García-Medrano, et alia. "The Earliest Acheulean Technology at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain): Oldest Levels of the Galería Site (Gii Unit)," Quaternary International 353:170-194:2014. Animals included:

Giant deer - Megaloceros solilhacus sspp

Fallow deer - Dama dama clactoniana

Red deer - Cervus elaphus priscus

Goat - Hemitragus bonali

Bison - Bison sp. (small),

Rhinoceros - Stephanorhinus cf. hemitoechus

Horse - Equus ferus, Equus cf. hydruntinus

Carnivores

Red fox - Vulpes vulpes

Wildcat - Felis sylvestris

_____ and Marina Mosquera. The Emergence of a Symbolic Behaviour: the Sepulchral Pit of Sima De Los Huesos, Sierra De Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain," Comptes Rendus Palevol 5:155-160:2006.

Pääbo, Svante, Matthias Meyer, et alia. "A Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of a Hominin from Sima De Los Huesos," Nature 505:403-406:2014.

Graphics:

1. NordNordWest. "Location Map of Konso, Ethiopia," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 11 September 2009.

2. Benito, José-Manuel. " Plan of La Trinchera del Ferrocarril, in the Archaeological Site of Atapuerca (Spain)," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, October 2002.

Sunday, June 14, 2015

Oldowan Life in Spain

Oldowan tool functions are unknown. Those who believed the earliest pre-human species were hunters argued they were used for butchering and for breaking bones to retrieve marrow or brains. Others said wear patterns on stone didn’t support that interpretation. Mary Douglas Leakey suggested some were used to pound plants. Her husband, Louis Leakey, thought the hominins were scavengers who ate remains of large mammals killed by carnivores.

Stone tools found in East African sites are so old, they don’t reveal the same information specialists can tease from Neanderthal artifacts. Bones have cut marks that could have come from butchering or hyenas or weathering. Geologists have only been able to confirm the Gona river area supported C4 grass. Pollen studies haven’t been able to identify available species.

At Sima del Elefante, in the Atapuerca, archaeologists have recovered bones of horses from every level, with bison, rhinoceroses, jaguars and lynx at the lowest level. They also found traces of conifers and oaks from the early years of the Pre-Pastorian glacial period around 1.3 million years ago.

In the higher strata they found evidence the climate alternated between colder and warmer. Right above the first layer, they found antlered deer, Irish elk, foxes and rabbits. Still higher, they again found bison, this time with charcoal. Then, the cave yielded antlered deer, Irish elk, foxes, lynxes, bears, and rabbits. At the top of that segment were remains of hippopotamuses, bison, bears, foxes, and rabbits.

More is known from the Aurora level of Gran Dolina at the close of the Pre-Pastorian period that ended just before the Brunhes-Matuyama polar reversal 781,000 years ago. The climate became progressive drier through strata that included remains of Homo antecessor. The number of species of small animals was increasing in an open environment with few forests.

One of the tools had been used to cut a hide, and another was used on wood. However, there is no evidence they used fire. Most tools were used to butcher animals. Evidence of plant use has not survived.

Carlos Díez’s group noted that most of the animal bones butchered in the cave were from small to medium sized mammals, like deer and boars. Deer antlers were "intensively chewed." The larger mammals included bison, horses, and Irish elk. Only teeth were found from rhinoceroses and mammoths, suggesting they were dismembered elsewhere and only the meatiest pieces brought inside. They didn’t mention rodents and rabbits. Any carnivore marks on bones came later.

The Homo antecessor bones also showed they’d been butchered. They were all from children or youth, of both sexes, up to an estimated age of twenty years. Eudald Carbonell’s team concluded people in the cave were cannibals. The dismembered bones appear in every level of the Aurora stratum at Gran Dolina, with no signs of rituals or famine associated with them. They simply were left with the other bones, tools and debris on the cave floor.

Notes:

Ash, Patricia J. and David J. Robinson. The Emergence of Humans, 2010.

Blumenschine, Robert J. "Characteristics of an Early Hominid Scavenging Niche," Current Anthropology 28:383-407:1987, with comments by others.

Carbonell, Eudald, et alia. "Cultural Cannibalism as a Paleoeconomic System in the European Lower Pleistocene: The Case of Level TD6 of Gran Dolina (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain)," Current Anthropology 51:539-549:2010.

Cerling, Thure E., et alia. "Woody Cover and Hominin Environments in the past 6? Million Years," Nature 476:51-56:2011.

Díez, J. Carlos, et alia. Zooarchaeology and Taphonomy of Aurora Stratum (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain)," Journal of Human Evolution 37:623-652:1999. Their list includes:

Small mammals

Fallow deer, roe deer

Wild boar - Sus scrofa

Medium mammals

Red deer

Generic deer - Cervidae

Large mammals

Bovid, Bison - Bison voigtstedtenensis

Horse - Equus stenonian

Irish Elk - Megaloceros

Very large mammals

Rhinoceros - Stephanorhinus etruscus

Mammoth - Mammuthus (only one)

Carnivores

Fox - Vulpes praeglacialis

Bear - Ursus dolinensis

Spotted hyena - Crocuta crocuta

Lynx - Lynx sp.

Leakey, Louis. Cited by G. Teleki, "The Omnivorous Diet and Eclectic Feeding Habits of Chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, Tanzania," in R. S. O. Harding, and G. Teleki, Omnivorous Primates, 1981.

Leakey, Mary. Cited by Nancy M. Tanner, On Becoming Human, 1981.

López Antoñanzas, Raquel and Gloria Cuenca Bescós. "The Gran Dolina Site (Lower to Middle Pleistocene, Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain): New Palaeoenvironmental Data Based on the Distribution of Small Mammals," Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 186:311-334:2002.

Quade, Jay, et alia. "Paleoenvironments of the Earliest Stone Toolmakers, Gona, Ethiopia," Geological Society of America, Bulletin 116:1529-1544:2004.

Rosas, A., et alia. "The "Sima del Elefante" cave site at Atapuerca (Spain)," Estudios Geológicos 62:327-348:2006. The species were:

Antlered deer - Eucladoceros giulli

Bison

Hippopotamus - Hippopotamus

Horse - Equus estenoniano

Irish elk - Megaloceros savinii

Rabbit

Rhinoceros - Rinocerotidae

Carnivores

Bear - Ursus dolinensis

Fox - Vulpes alopecoides

Jaguar - Panthera gombaszoegensis

Lynx - Lynx issodorensis

Photograph: Mario Modesto Mata, "Sierra de Atapuerca," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 22 July 2006.

Stone tools found in East African sites are so old, they don’t reveal the same information specialists can tease from Neanderthal artifacts. Bones have cut marks that could have come from butchering or hyenas or weathering. Geologists have only been able to confirm the Gona river area supported C4 grass. Pollen studies haven’t been able to identify available species.

At Sima del Elefante, in the Atapuerca, archaeologists have recovered bones of horses from every level, with bison, rhinoceroses, jaguars and lynx at the lowest level. They also found traces of conifers and oaks from the early years of the Pre-Pastorian glacial period around 1.3 million years ago.

In the higher strata they found evidence the climate alternated between colder and warmer. Right above the first layer, they found antlered deer, Irish elk, foxes and rabbits. Still higher, they again found bison, this time with charcoal. Then, the cave yielded antlered deer, Irish elk, foxes, lynxes, bears, and rabbits. At the top of that segment were remains of hippopotamuses, bison, bears, foxes, and rabbits.

More is known from the Aurora level of Gran Dolina at the close of the Pre-Pastorian period that ended just before the Brunhes-Matuyama polar reversal 781,000 years ago. The climate became progressive drier through strata that included remains of Homo antecessor. The number of species of small animals was increasing in an open environment with few forests.

One of the tools had been used to cut a hide, and another was used on wood. However, there is no evidence they used fire. Most tools were used to butcher animals. Evidence of plant use has not survived.

Carlos Díez’s group noted that most of the animal bones butchered in the cave were from small to medium sized mammals, like deer and boars. Deer antlers were "intensively chewed." The larger mammals included bison, horses, and Irish elk. Only teeth were found from rhinoceroses and mammoths, suggesting they were dismembered elsewhere and only the meatiest pieces brought inside. They didn’t mention rodents and rabbits. Any carnivore marks on bones came later.

The Homo antecessor bones also showed they’d been butchered. They were all from children or youth, of both sexes, up to an estimated age of twenty years. Eudald Carbonell’s team concluded people in the cave were cannibals. The dismembered bones appear in every level of the Aurora stratum at Gran Dolina, with no signs of rituals or famine associated with them. They simply were left with the other bones, tools and debris on the cave floor.

Notes:

Ash, Patricia J. and David J. Robinson. The Emergence of Humans, 2010.

Blumenschine, Robert J. "Characteristics of an Early Hominid Scavenging Niche," Current Anthropology 28:383-407:1987, with comments by others.

Carbonell, Eudald, et alia. "Cultural Cannibalism as a Paleoeconomic System in the European Lower Pleistocene: The Case of Level TD6 of Gran Dolina (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain)," Current Anthropology 51:539-549:2010.

Cerling, Thure E., et alia. "Woody Cover and Hominin Environments in the past 6? Million Years," Nature 476:51-56:2011.

Díez, J. Carlos, et alia. Zooarchaeology and Taphonomy of Aurora Stratum (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain)," Journal of Human Evolution 37:623-652:1999. Their list includes:

Small mammals

Fallow deer, roe deer

Wild boar - Sus scrofa

Medium mammals

Red deer

Generic deer - Cervidae

Large mammals

Bovid, Bison - Bison voigtstedtenensis

Horse - Equus stenonian

Irish Elk - Megaloceros

Very large mammals

Rhinoceros - Stephanorhinus etruscus

Mammoth - Mammuthus (only one)

Carnivores

Fox - Vulpes praeglacialis

Bear - Ursus dolinensis

Spotted hyena - Crocuta crocuta

Lynx - Lynx sp.

Leakey, Louis. Cited by G. Teleki, "The Omnivorous Diet and Eclectic Feeding Habits of Chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, Tanzania," in R. S. O. Harding, and G. Teleki, Omnivorous Primates, 1981.

Leakey, Mary. Cited by Nancy M. Tanner, On Becoming Human, 1981.

López Antoñanzas, Raquel and Gloria Cuenca Bescós. "The Gran Dolina Site (Lower to Middle Pleistocene, Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain): New Palaeoenvironmental Data Based on the Distribution of Small Mammals," Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 186:311-334:2002.

Quade, Jay, et alia. "Paleoenvironments of the Earliest Stone Toolmakers, Gona, Ethiopia," Geological Society of America, Bulletin 116:1529-1544:2004.

Rosas, A., et alia. "The "Sima del Elefante" cave site at Atapuerca (Spain)," Estudios Geológicos 62:327-348:2006. The species were:

Antlered deer - Eucladoceros giulli

Bison

Hippopotamus - Hippopotamus

Horse - Equus estenoniano

Irish elk - Megaloceros savinii

Rabbit

Rhinoceros - Rinocerotidae

Carnivores

Bear - Ursus dolinensis

Fox - Vulpes alopecoides

Jaguar - Panthera gombaszoegensis

Lynx - Lynx issodorensis

Photograph: Mario Modesto Mata, "Sierra de Atapuerca," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 22 July 2006.

Thursday, June 11, 2015

Spain’s Oldowan Technology

Early human history is the record of technological advances. Tools made from stone survive. Geology was the first science.

The earliest have been found in Gona, Ethiopia, located at the northern end of the East African rift valley in the Afar triangle where the Arabian, Somalian and main African plates are pulling away from each other. Olduvai Gorge, which gave its name to the technology, is at the southern end of the valley in modern Tanzania.

Gona tools have been dated to 2.6 million years ago. That’s just before the Gauss-Matuyama reversal in the Earth’s magnetic field at the beginning of the Pleistocene. Many had volcanic origins. Tool makers held a rock with one hand and struck it with another rock held by the other hand. The chips or flakes were the tool, not the diminished stone. Most had an edge on one side. They looked like choppers and scrappers.

The trachytic basalt cobbles were taken from a nearby stream, and carried elsewhere to be worked. The stone workers, usually called flint knappers, selected fine-grained rocks. The fact other rocks were available indicated they had spent time observing stones and remembering the ones with best qualities.

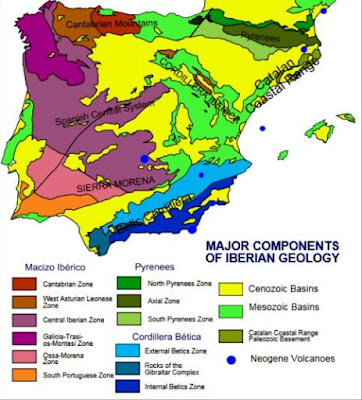

Technology is transportable. Gona’s techniques spread from Africa, where they were used until 1.7 million year ago. Although the above map only shows significant sites in Asia and Europe, Oldowan tools have been recorded in northern Spain after the industry faded from the Rift Valley. Sima del Elefante has artifacts made from chert, quartz, and limestone dated between 1.4 and 1.1 million years. Gran Dolina has quartzite tools from 800,000 years ago.

Both caves are in the Atapuerca formation less than 10 miles east of Burgos. The isolated limestone formation stood above waters running through the Bureba Pass pass between the Cantabrian mountains to the north and the Sistema Iberia abutting from the south during the Cenozoic. It’s the narrow yellow section toward the north on the map below.

The Oldowan quartzite probably came from terraces of the Arlanzón river that flows through Burgos to meet a tributary of the Duero. The Atapuerca chert formed in the later Miocene when silica grew into nodules within the limestone. Flint forms when the limestone is chalky. Limestone is a form of calcium carbonate.

The basalt of Gona and the quartzite and chert of Atapuerca contain silica dioxide (SiO2), the major component in glass and in sand. They break along clear planes with sharp edges, but those planes aren’t visible like they are with mica. Sileshi Semaw believed the ability to fracture them by striking signified a high level of skill and coordination.

Manufacturing techniques and their associated economies survived changes in biology and culture. The earliest bones associated with Oldowan tools were Australopithecus garhi. The modified rocks also have been found with Homo habilis, Homo ergaster, and Homo erectus.

The Gona tools were found along a tributary of the Awash river, upstream and a bit west of Hadar where Lucy, the oldest human ancestor, was found. The Australopithecus afarensis remains are 3.2 million years old. They haven’t been associated with tools.

At Gran Dolina the Oldowan technology was expanded to include chips of different sizes used for different purposes by Homo antecessor. José Bermúdez de Castro’s team believed the species was the immediate ancestor of Neanderthals. While it had the nasal area of the modern species, its jaws and teeth were like those of Homo erectus.

Innovation has two phases. First comes the invention of a technique, then the modification of that idea to fit new circumstances. Both involve a willingness to experiment, an ability to learn from experience, and an expectation of repeatability. Anyone can throw a rock at a boulder to break off a chip, but only a tool maker will watch the arc and aim another to change the outcome to fit a desired end.

Notes:

Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., et alia. "A Hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: Possible Ancestor to Neandertals and Modern Humans," Science 276:1392-1395:1997.

Carbonell, Eudald, Paula García-Medrano, et alia. "The Earliest Acheulean Technology at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain): Oldest Levels of the Galería Site (Gii Unit)," Quaternary International 353:170-194:2014.

Semaw, Sileshi. "The World’s Oldest Stone Artefacts from Gona, Ethiopia: Their Implications for Understanding Stone Technology and Patterns of Human Evolution Between 2.6-1.5 Million Years Ago," Journal of Archaeological Science 27:1197-1214:2000.

____, Jay Quade, et alia. "Paleoenvironments of the Earliest Stone Toolmakers, Gona, Ethiopia," Geological Society of America, Bulletin 116:1529-1544:2004.

Toro Moyano, Isidro, et alia. "The Archaic Stone Tool Industry from Barranco León and Fuente Nueva 3, (Orce, Spain): Evidence of the Earliest Hominin Presence in Southern Europe," Quaternary International 243:80-91:2011.

Graphics:

1. Anonymous map of "Oldowan Sites," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 28 October 2010.

2. Efe, PePe. "Geological Units of the Iberian Peninsula," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 11 March 2013, translated by Graeme Bartlett.

The earliest have been found in Gona, Ethiopia, located at the northern end of the East African rift valley in the Afar triangle where the Arabian, Somalian and main African plates are pulling away from each other. Olduvai Gorge, which gave its name to the technology, is at the southern end of the valley in modern Tanzania.

Gona tools have been dated to 2.6 million years ago. That’s just before the Gauss-Matuyama reversal in the Earth’s magnetic field at the beginning of the Pleistocene. Many had volcanic origins. Tool makers held a rock with one hand and struck it with another rock held by the other hand. The chips or flakes were the tool, not the diminished stone. Most had an edge on one side. They looked like choppers and scrappers.

The trachytic basalt cobbles were taken from a nearby stream, and carried elsewhere to be worked. The stone workers, usually called flint knappers, selected fine-grained rocks. The fact other rocks were available indicated they had spent time observing stones and remembering the ones with best qualities.

Technology is transportable. Gona’s techniques spread from Africa, where they were used until 1.7 million year ago. Although the above map only shows significant sites in Asia and Europe, Oldowan tools have been recorded in northern Spain after the industry faded from the Rift Valley. Sima del Elefante has artifacts made from chert, quartz, and limestone dated between 1.4 and 1.1 million years. Gran Dolina has quartzite tools from 800,000 years ago.

Both caves are in the Atapuerca formation less than 10 miles east of Burgos. The isolated limestone formation stood above waters running through the Bureba Pass pass between the Cantabrian mountains to the north and the Sistema Iberia abutting from the south during the Cenozoic. It’s the narrow yellow section toward the north on the map below.

The Oldowan quartzite probably came from terraces of the Arlanzón river that flows through Burgos to meet a tributary of the Duero. The Atapuerca chert formed in the later Miocene when silica grew into nodules within the limestone. Flint forms when the limestone is chalky. Limestone is a form of calcium carbonate.

The basalt of Gona and the quartzite and chert of Atapuerca contain silica dioxide (SiO2), the major component in glass and in sand. They break along clear planes with sharp edges, but those planes aren’t visible like they are with mica. Sileshi Semaw believed the ability to fracture them by striking signified a high level of skill and coordination.

Manufacturing techniques and their associated economies survived changes in biology and culture. The earliest bones associated with Oldowan tools were Australopithecus garhi. The modified rocks also have been found with Homo habilis, Homo ergaster, and Homo erectus.

The Gona tools were found along a tributary of the Awash river, upstream and a bit west of Hadar where Lucy, the oldest human ancestor, was found. The Australopithecus afarensis remains are 3.2 million years old. They haven’t been associated with tools.

At Gran Dolina the Oldowan technology was expanded to include chips of different sizes used for different purposes by Homo antecessor. José Bermúdez de Castro’s team believed the species was the immediate ancestor of Neanderthals. While it had the nasal area of the modern species, its jaws and teeth were like those of Homo erectus.

Innovation has two phases. First comes the invention of a technique, then the modification of that idea to fit new circumstances. Both involve a willingness to experiment, an ability to learn from experience, and an expectation of repeatability. Anyone can throw a rock at a boulder to break off a chip, but only a tool maker will watch the arc and aim another to change the outcome to fit a desired end.

Notes:

Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., et alia. "A Hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: Possible Ancestor to Neandertals and Modern Humans," Science 276:1392-1395:1997.

Carbonell, Eudald, Paula García-Medrano, et alia. "The Earliest Acheulean Technology at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain): Oldest Levels of the Galería Site (Gii Unit)," Quaternary International 353:170-194:2014.

Semaw, Sileshi. "The World’s Oldest Stone Artefacts from Gona, Ethiopia: Their Implications for Understanding Stone Technology and Patterns of Human Evolution Between 2.6-1.5 Million Years Ago," Journal of Archaeological Science 27:1197-1214:2000.

____, Jay Quade, et alia. "Paleoenvironments of the Earliest Stone Toolmakers, Gona, Ethiopia," Geological Society of America, Bulletin 116:1529-1544:2004.

Toro Moyano, Isidro, et alia. "The Archaic Stone Tool Industry from Barranco León and Fuente Nueva 3, (Orce, Spain): Evidence of the Earliest Hominin Presence in Southern Europe," Quaternary International 243:80-91:2011.

Graphics:

1. Anonymous map of "Oldowan Sites," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 28 October 2010.

2. Efe, PePe. "Geological Units of the Iberian Peninsula," uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, 11 March 2013, translated by Graeme Bartlett.

Tuesday, June 09, 2015

Ice Age Española

The great glaciers of the Pleistocene were more real in Michigan where I grew up than they are in the Española valley. As a child I imagined a great blanket of snow called Illinois sidling over my neighborhood, then retreating, only to reappear in a few thousand years as the Wisconsin glacier.

Archaeologists today don’t mention glacial episodes for sites that weren’t under ice. They prefer to use the marine isotope stages developed by Cesare Emiliani and Nicholas Shackleton. The MIS numbers demarcate variations in ice composition that occurred when expanding glaciers monopolized the lighter oxygen isotopes in water, leaving the heavier ones in sea beds. Even MIS numbers are cold periods, odd numbers warm.

[Click on table to enlarge]

The stages have the advantage of avoiding labels specific to Europe and North America and help define relationships between the different ice sheets. In New Mexico, the Bull Lake glacier occurred during the Illinois in the northeast and the Riss in Europe. The ice was centered in northwestern Montana and reached down to the San Juan mountains in southern Colorado.

The later Pinedale coincided with the Wisconsin and the European Würm. It’s icecap rested on the Yellowstone Plateau, but it left glacial lakes in the Sangre de Cristo: Katherine and Nambé near Santa Fé Baldy, Horseshoe in the headwaters of the Red River.

Scott Renbarger believed the trees blown down near Trailrider Wall were growing in a moraine. Ponderosa pine roots reach deep when there’s no surface water, but only go 3' down in water-retentive soils. Rocks can trap water to create undemanding environments.

Abandoning the names of glaciers obscures the fact their affects were felt far away. When glaciers were expanding they absorbed water that otherwise would have fallen as rain. Areas beyond the ice fields dried. Winds blew their dust against mountains, grinding rock surfaces into particles that fell into great dune fields. The Great Plains and the rich farm lands of the Danube River valley began as Pleistocene aeolian deposits.

Stephen Hall said the dominant species in San Juan County and the Chuska Mountains during cold spells were piñon and Ponderosa pine. Limber pine also grew in San Juan County. Sagebrush grew in the warmer periods called interglacials. In those millennia, water was released, lakes formed, and rivers were swollen by rain.

In the Española valley the released waters sometimes brought down boulders that temporarily blocked White Rock Canyon. Then floods formed wetlands that filled existing lowlands and left a deceptively level surface. When the waters receded, they left behind badlands that border the eastern valley.

The badlands east of Llano Road between the high school and the Santa Cruz cemetery are fingers of fine-grained sand, siltstone and sandstone. Daniel Koning suspected they "may possibly lie near the north edge of a former playa or lake."

Farther north, east of San Juan Pueblo, rocks from the Middle to Upper Pleistocene have been judged 50,000 to 300,000 years old. About 25 to 40% of the pebbles are cobble sized. A bit south toward the casino, there are fewer cobbles, 10 to 30%. The "light yellowish brown to very pale brown pebbly sand" contains some quartzite. Sitting atop the eastern badlands, wind driven sand remains.