Differences between Nouvelle-France Jesuits and Nuevo México Franciscans probably had less to do with beliefs of their founders than with ways their orders served the kings upon whom they were dependent.

In Spain, all priests, regardless of order, were expected to serve as arms of the Inquisition. They were trained to spot signs of covert Jewishness. Parishioners, like Leonor Domínguez, learned to maintain outward manifestations of faith, even when under duress. Everyone judged the Españolness of others.

When Franciscans came north with Juan de Oñate and Diego de Varga they did nothing to convert sedentary pueblos. Military leaders pacified settlements, then assigned priests to administer them. That meant transforming adults and older children into laborers who behaved like Españoles. Priests were expected to report any seditious behavior.

Natives weren’t actually accorded the status of Españoles, but were defined as children being guided by fathers. Their marriages weren’t scrutinized in the same way. Angélico Chávez said, they didn’t submit diligencias matrimoniales.

When priests found kivas and dances persisted before the Revolt, they didn’t try to persuade. They asked the state to intervene. When they discovered pueblos hadn’t altered their marriage ways, the 1714 governor, Juan Flores Magollón, "ordered that married couples in Indian pueblos should live together rather than with their individual parents, as was the custom." He saw it as a "reversion to Indian habits that the Spanish were trying to break."

Explorers in New France found no easily exploitable natural resources. They did find fur. They were able to convert native bands into commercial hunters who traded pelts for European goods. Traders had no choice but to learn the languages and trading rituals of natives. If the priests wanted to convert mobile societies, they had to follow traders and persuade by example.

In 1700, when the War of Spanish Succession began, alliances with native groups became critical to the military success of France, England, and Spain. When the missionary François-Jolliet de Montigny settled with the Taensa near the confluence of the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers in 1703, he didn’t destroy their temple.

When a smallpox epidemic ravaged the village, he baptized dying infants and those adults he believed understood the purpose of his prayers. When the chief died, he didn’t interfere with the death rituals. He only acted to persuade people not to make human sacrifices.

He was away when the temple burned and women began throwing infants into the fire. It was only then other Frenchmen in the village contravened native customs.

Like the coureurs and priests Juan de Ulibarrí was expected to provide information on indios bárbaros when he went to El Cuartelejo for the governor. He reported the Jicarilla "were very good people; that had not stolen anything from anyone, but occupied themselves with their maize and corn fields which they harvest, because they are busy with the sowing of corn, frijoles, and pumpkins."

After talking with the El Cuartelejo, he wrote: "The first thing is they are more inclined toward our Catholic faith than any of those that are thus reduced." He added, "at the end of July they had gathered crops of Indian corn, watermelons, pumpkins, and kidney beans [...] So that, because of the fertility of the land, the docility of the people, and the abundance of buffalo, and other game, the propagation of our holy Catholic faith could be advanced very much."

Compare that to the 1673 meeting between the Jesuit priest, Jacques Marquette, and the Illinois. He described the calumet dance in detail, and noted: "They have several wives, of whom they are Extremely jealous; they watch them very closely, and Cut off Their noses or ears when they misbehave." Of their food, he said:

"They live by hunting, game being plentiful in that country, and on indian corn, of which they always have a good crop; consequently, they have never suffered from famine. They also sow beans and melons, which are Excellent, especially those that have red seeds. Their Squashes are not of the best; they dry them in the sun, to eat them during The winter and the spring."

He adds, "Their Cabins are very large, and are Roofed and floored with mats made of Rushes" and "They are liberal in cases of illness, and Think that the effect of the medicines administered to them is in proportion to the presents given to the physician."

It was perhaps too much to expect soldiers to make the same kind of ethnographic observations as priests. It wasn’t simply that the ones were more educated than the others. The ability of a good military leader to locate water in barren lands and ensure the safety of hundreds of horses in treacherous terrain was simply different.

Ulibarrí had a priest with him. So far as I know, he made no report. He stayed with the Spaniards when Ulibarrí was meeting with El Cuartelejo leaders. It was only after the chief took them to a cross that Domingo de Aranz appeared to consummate the pacification and intone "the Te Deum Laudemus and the rest of the prayers and sang three times the hymn in praise of the sacrament."

They were given a hymn of praise, but not a full mass. They weren’t yet professors of the faith.

Notes: Montigny was one of the missionaries sent by the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères in 1698; see posting for 17 May 2015.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Flores Magollón, Juan Ignacio. Order, 30 April 1714, quoted by Frederic J. Athearn in A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978. The translation does not indicate which pueblo was involved.

Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade, 2002; on Montigny.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Saturday, May 30, 2015

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Santa Cruz Militia Rosters

The identities of many who served in these years from Santa Cruz, Santa Clara and San Juan are lost. No roster survives from Roque de Madrid’s 1705 campaign against the Navajo. The man who chronicled the campaign, Antonio Álvarez Castrillón, mentioned few in the company. He did, however, remark the skills of Juan Roque Gutíerrez, the campaign captain who guided the horses through "the middle of a forest so thick and close that the animals got stuck."

There’s no published roster for Juan de Ulibarrí’s expedition the next year to El Cuartelejo. He says he received an "enlistment list" that included 28 from the presidio, 12 from the militia, and 100 auxiliaries. He added men went he stopped at Picurís.

Ulibarrí is the only one who signed his report. In it he mentions Sargento Bartolomé Sánchez, who found a ford across a swollen stream. Later he sends Ensign Ambrosia Fresqui and Capitán José López Naranjo to find water. Ulibarrí also names Francisco de Valdés and Jean l’Archevêque.

Castrillón’s report was signed by nine men, besides himself and Madrid. Six had ties to Santa Cruz: José Domínguez de Mendoza, Cristóbal de la Serna, Juan Roque Gutíerrez, Miguel de Herrera, José López Naranjo, and Mateo Trujillo. The first two were capitánes whose families had lived in the Río Abajo before the Revolt.

The second two were soldiers from the presidio. Gutíerrez had married the daughter of a capitán, Luis Martín, in 1690. Herrera was raised in La Cañada. Both were the sons of soldiers. Trujillo had come north as a soldier, then claimed land. On this expedition he was a squadron leader.

The other signatories included two who were part of the presidio and later assigned to Santa Cruz as alcaldes: Cristóbal de Arellano and Tomás López Holguín. Martín García was also part of the presidio. He’s the one who would be exiled in 1710 for abusing native workers at Galisteo.

As for the auxiliaries, Madrid noted sixteen joined them from Tesuque, when they were en route to Picurís, and forty came there from Taos. In addition he mentioned Pamuje, a Tewa speaker, and Dirucaca from Jémez as men who gave him conflicting advice on a route. When he wanted to distract the Navajo while he positioned men to attack, he sent Naranjo and the governor of Zia. Their seconds were Juan Griego from San Juan and another war captain.

The other capitánes, militia men and auxiliaries were anonymous. Only one was killed, "and he was an Indian."

Notes:

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; biographies of men mentioned in journal.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

There’s no published roster for Juan de Ulibarrí’s expedition the next year to El Cuartelejo. He says he received an "enlistment list" that included 28 from the presidio, 12 from the militia, and 100 auxiliaries. He added men went he stopped at Picurís.

Ulibarrí is the only one who signed his report. In it he mentions Sargento Bartolomé Sánchez, who found a ford across a swollen stream. Later he sends Ensign Ambrosia Fresqui and Capitán José López Naranjo to find water. Ulibarrí also names Francisco de Valdés and Jean l’Archevêque.

Castrillón’s report was signed by nine men, besides himself and Madrid. Six had ties to Santa Cruz: José Domínguez de Mendoza, Cristóbal de la Serna, Juan Roque Gutíerrez, Miguel de Herrera, José López Naranjo, and Mateo Trujillo. The first two were capitánes whose families had lived in the Río Abajo before the Revolt.

The second two were soldiers from the presidio. Gutíerrez had married the daughter of a capitán, Luis Martín, in 1690. Herrera was raised in La Cañada. Both were the sons of soldiers. Trujillo had come north as a soldier, then claimed land. On this expedition he was a squadron leader.

The other signatories included two who were part of the presidio and later assigned to Santa Cruz as alcaldes: Cristóbal de Arellano and Tomás López Holguín. Martín García was also part of the presidio. He’s the one who would be exiled in 1710 for abusing native workers at Galisteo.

As for the auxiliaries, Madrid noted sixteen joined them from Tesuque, when they were en route to Picurís, and forty came there from Taos. In addition he mentioned Pamuje, a Tewa speaker, and Dirucaca from Jémez as men who gave him conflicting advice on a route. When he wanted to distract the Navajo while he positioned men to attack, he sent Naranjo and the governor of Zia. Their seconds were Juan Griego from San Juan and another war captain.

The other capitánes, militia men and auxiliaries were anonymous. Only one was killed, "and he was an Indian."

Notes:

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; biographies of men mentioned in journal.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Santa Cruz Militia

Two military ranks appeared in diligencias matrimoniales: capitánes of the militia and soldiers in the presidio. The latter included sargentos and sargento mayors. Other ranks existed in Santa Fé, but these were the ones known in Santa Cruz.

Thomas Naylor said New Spain paid its soldiers so poorly, few would enlist. Only the worst were turned away. In 1708, charges were brought against Martín García and six men under his command for mistreating men at Galisteo. Cristóbal Lucero stabbed one in the head. Miguel Durán threw others off scaffolds. García himself ordered Lorenzo Rodríguez to tie, hang, and whip a man.

There was no death penalty for Lucero killing a man. The Duque de Albuquerque wanted him sentenced to a distant presidio and the others warned. The viceroy was overruled by his auditor generals of war. In 1710, they suggested García also be sentenced to another presidio and Durán be warned. One of the pardoned, Alonso Garcia de Noriega, was the nephew of Leonor Domínguez and Alonso Rael de Aguilar. Their uncle Lázaro had been killed at Galisteo in 1680.

Low wages meant few soldiers could afford families. With no patrimony, their sons enlisted and their daughters had few prospects. The only man who married in Santa Cruz in these years was a second generation soldier. Miguel Tenorio de Alba had risen to capitán by the time he wed Agustína Romero in 1705. She was the daughter of Salvador Romero and María López de Ocanto.

The only military men called to witness Santa Cruz weddings were Sargento Ambrosio Fresqui in 1703 and Alonso Fernandéz in 1701. The one was likely the son or grandson of Capitán Juan Fresqui. The other had come from Sombrerete with his father. Capitán Juan Fernandéz de la Pedrera had migrated from Galicia.

A division without a name existed between militia capitáns and their men. Francisco Cuervo reviewed the troops in Santa Cruz in April of 1705. Eight-three men showed, but only twenty-three had horses or mules. Twenty-two had no weapons. It’s not known if two-thirds of the men had had animals they sold, if the animals they had been issued when the villa was settled had grown old, or if they never had had horses or mules.

When Roque de Madrid pursued the Navajo in August of that year, all the men were mounted and had spare animals. Cuervo had brought 600 horses from Nuevo Vizcaya. There were more than 700 horses in Madrid’s campaign herd, including those of the "Indian allies."

When Madrid started across the highlands west of the Tusas, he sent "war captains from the Tewa and Picurís nations" ahead to suggest a route. When they returned, "they laid before me as many difficulties and inconveniences as they possibly could." He ignored them to "follow the slope and the breaks of the mountains by a route no Spaniard or person from any other nation had taken until now," but did take the precaution of doubling the squadron for the horses.

A few days later, he sent his scouts ahead again, and "they returned to me and raised even greater objections to my entrada." Madrid "paid them no heed, because my mind was made up to continue until I saw everything to its conclusion."

Juan de Ulibarrí was sent across the prairies to El Cuartelejo in 1706. They met other Apache who warned them of dangerous bands ahead. He thanked them for their advice, "but I was trusting in our God who was the creator of everything and who was to keep us free from the present dangers."

Later, after they had crossed the Arkansas river, Ulibarrí’s pueblo guides warned him, "we would undergo much suffering because there was no water." The men got lost following hummocks of grass left as a trail by the Apache, but two scouts did find water. The next day, they got lost again. This time "I, with the experience of the preceding day, scattered the whole command" and so found a dry arroyo with a spring.

After they had fought several successful battles with the Navajo, Madrid called a council of "active officials, military leaders, and reserves." The horses were suffering, the men were sick from eating green corn. He asked what was "appropriate" for "a soldier’s honor."

They answered, the enemy would now hide from fear of their weapons, and so little would be gained from pursuing them. They felt it was time to "withdraw our forces to the royal presidio."

When Ulibarrí needed to violate colonial policy against arming natives by providing them with a gun in exchange for one they had taken from the Pawnee, he called a meeting of his advisors. "We had agreed by common consent that it was better to hand it over to them so that in no way should they lack confidence in our word."

There was one other division within the military, the one between men like Madrid and Ulibarrí and the men they commanded. When he was determining the best strategy for dealing with the Navajo, Madrid said he feared "the treachery of these barbarians because of my many years of experience fighting them."

But it was more than experience. It took judgement, intuition and an ability to learn from the unexpected to chart paths through unexplored wilderness, intelligence to devise ruses to trick the Navajo, and wisdom to listen to the tenor of what men said.

Such military virtues were universally recognized. Jacques Marquette said of his commander, Louis Joliet: "He possesses Tact and prudence, which are the chief qualities necessary for the success of a voyage as dangerous as it is difficult. Finally, he has the Courage to dread nothing where everything is to be Feared."

Notes: The roster doesn’t exist from Madrid’s campaign, so it’s impossible to know how many horses were available to each man.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks; Madrid quotations.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; on Cuervo.

Naylor, Thomas H., Diana Hadley, and Mardith K. Schuetz-Miller. The Presidio and Militia on the Northern Frontier of New Spain, volume 2, part 2, 1997; on trial of Martín García. The records they transcribed didn’t name all six men.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Thomas Naylor said New Spain paid its soldiers so poorly, few would enlist. Only the worst were turned away. In 1708, charges were brought against Martín García and six men under his command for mistreating men at Galisteo. Cristóbal Lucero stabbed one in the head. Miguel Durán threw others off scaffolds. García himself ordered Lorenzo Rodríguez to tie, hang, and whip a man.

There was no death penalty for Lucero killing a man. The Duque de Albuquerque wanted him sentenced to a distant presidio and the others warned. The viceroy was overruled by his auditor generals of war. In 1710, they suggested García also be sentenced to another presidio and Durán be warned. One of the pardoned, Alonso Garcia de Noriega, was the nephew of Leonor Domínguez and Alonso Rael de Aguilar. Their uncle Lázaro had been killed at Galisteo in 1680.

Low wages meant few soldiers could afford families. With no patrimony, their sons enlisted and their daughters had few prospects. The only man who married in Santa Cruz in these years was a second generation soldier. Miguel Tenorio de Alba had risen to capitán by the time he wed Agustína Romero in 1705. She was the daughter of Salvador Romero and María López de Ocanto.

The only military men called to witness Santa Cruz weddings were Sargento Ambrosio Fresqui in 1703 and Alonso Fernandéz in 1701. The one was likely the son or grandson of Capitán Juan Fresqui. The other had come from Sombrerete with his father. Capitán Juan Fernandéz de la Pedrera had migrated from Galicia.

A division without a name existed between militia capitáns and their men. Francisco Cuervo reviewed the troops in Santa Cruz in April of 1705. Eight-three men showed, but only twenty-three had horses or mules. Twenty-two had no weapons. It’s not known if two-thirds of the men had had animals they sold, if the animals they had been issued when the villa was settled had grown old, or if they never had had horses or mules.

When Roque de Madrid pursued the Navajo in August of that year, all the men were mounted and had spare animals. Cuervo had brought 600 horses from Nuevo Vizcaya. There were more than 700 horses in Madrid’s campaign herd, including those of the "Indian allies."

When Madrid started across the highlands west of the Tusas, he sent "war captains from the Tewa and Picurís nations" ahead to suggest a route. When they returned, "they laid before me as many difficulties and inconveniences as they possibly could." He ignored them to "follow the slope and the breaks of the mountains by a route no Spaniard or person from any other nation had taken until now," but did take the precaution of doubling the squadron for the horses.

A few days later, he sent his scouts ahead again, and "they returned to me and raised even greater objections to my entrada." Madrid "paid them no heed, because my mind was made up to continue until I saw everything to its conclusion."

Juan de Ulibarrí was sent across the prairies to El Cuartelejo in 1706. They met other Apache who warned them of dangerous bands ahead. He thanked them for their advice, "but I was trusting in our God who was the creator of everything and who was to keep us free from the present dangers."

Later, after they had crossed the Arkansas river, Ulibarrí’s pueblo guides warned him, "we would undergo much suffering because there was no water." The men got lost following hummocks of grass left as a trail by the Apache, but two scouts did find water. The next day, they got lost again. This time "I, with the experience of the preceding day, scattered the whole command" and so found a dry arroyo with a spring.

After they had fought several successful battles with the Navajo, Madrid called a council of "active officials, military leaders, and reserves." The horses were suffering, the men were sick from eating green corn. He asked what was "appropriate" for "a soldier’s honor."

They answered, the enemy would now hide from fear of their weapons, and so little would be gained from pursuing them. They felt it was time to "withdraw our forces to the royal presidio."

When Ulibarrí needed to violate colonial policy against arming natives by providing them with a gun in exchange for one they had taken from the Pawnee, he called a meeting of his advisors. "We had agreed by common consent that it was better to hand it over to them so that in no way should they lack confidence in our word."

There was one other division within the military, the one between men like Madrid and Ulibarrí and the men they commanded. When he was determining the best strategy for dealing with the Navajo, Madrid said he feared "the treachery of these barbarians because of my many years of experience fighting them."

But it was more than experience. It took judgement, intuition and an ability to learn from the unexpected to chart paths through unexplored wilderness, intelligence to devise ruses to trick the Navajo, and wisdom to listen to the tenor of what men said.

Such military virtues were universally recognized. Jacques Marquette said of his commander, Louis Joliet: "He possesses Tact and prudence, which are the chief qualities necessary for the success of a voyage as dangerous as it is difficult. Finally, he has the Courage to dread nothing where everything is to be Feared."

Notes: The roster doesn’t exist from Madrid’s campaign, so it’s impossible to know how many horses were available to each man.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks; Madrid quotations.

Chávez, Angélico. New Mexico Roots, Ltd, 1982.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; on Cuervo.

Naylor, Thomas H., Diana Hadley, and Mardith K. Schuetz-Miller. The Presidio and Militia on the Northern Frontier of New Spain, volume 2, part 2, 1997; on trial of Martín García. The records they transcribed didn’t name all six men.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Labels:

01 Domínguez,

01 Madrid,

01 Ulibarrí,

09 Santa Cruz 11-15

Sunday, May 24, 2015

Pueblo War Rituals

Santa Clara and San Juan gained two thing by cooperating with the governors’ requests for auxiliaries. When they reported Navajo incursions, they could summon larger forces than they could mount alone. More importantly, they could continue traditional military practices while appearing to submit.

When they mustered for the Spanish, they were with their own war captains. Within campaigns, they were commanded by pueblo leaders. In 1706, it was Domingo Romero Yaguaque of Tesuque who served as capitán mayor de la guerra. In 1708, Romero and Felipe of Pecos served Juan de Ulibarrí.

Scouts were almost always from the pueblos. Diego de Vargas used José López Naranjo as his lead against the Faraón in the Sandías in 1704. Roque de Madrid used him when they chased the Navajo west the follow year. Ulibarrí used the scout with Jean de l’Archevêque when they ventured onto the plains in 1706. In 1713, Naranjo was capitán mayor against the Navajo.

Warriors continued using their traditional methods. During the 1705 campaign, they scalped the Navajo men. Antonio Álvarez Castrillón said, there were:

"many more deaths that the Indian allies will have carried out among the women and chusma over the distance they covered on top of the mesa. This is their custom, and no matter how much I reproach them, they neither take heed nor pay attention unless Spaniards are present."

Post-battle rituals were maintained, at least until 1712 when José Chacón banned them. Then they continued surreptitiously.

He reported the pueblos: "keep the scalps taken from their enemies, the unfaithful enemies whom they kill in battle, bring them and dance publicly." He speculated on what happened later in the kivas where "they invoke the devil, and in his company and with his advice and suggestion they exhort one thousand errors."

What actually happened in the kivas was probably more subtle that the witchcraft imagined by Juan de la Peña, the Franciscan custodio in 1709, or by Chacón in 1712. The governors only knew they asked pueblo alcaldes to bring specified numbers of men. They had no idea if particular warriors were selected because they were the most experienced or were initiates who needed to prove themselves.

They certainly had no idea if there were any kinship or other special relationships between the men. Commanders only recorded the numbers from each pueblo on the muster rolls, not names. Sometimes, all that survives in documents is the total number of auxiliaries, or a mere acknowledgment they were present.

In 1706, Juan Álvarez estimated there were about 210 "Christian persons, large and small" at Santa Clara and 340 at San Juan. If one assumes 30% of the male population was the right age, and only 40% of the population was male after the battles of the Reconquest, there would still have been 25 available men at the one and 40 at the other. In 1704, Santa Clara’s quota, including war captains, was five, and San Juan’s six.

Commanders knew pueblo warriors painted themselves and wore feathers when they went into battle. Soldiers and settlers camped separately from auxiliaries. They had no idea what occurred before battles when men from different pueblos prepared themselves.

Cuervo believed the auxiliaries were "satisfied with the useful spoils of war." He didn’t recognize traditional male roles, social groups, and status hierarchies were being reinforced by opportunities to continue doing what ought to be done - punishing those who had harmed the pueblos - at a time when his regime might have been undermining traditional leaders by overseeing the elections of internal governors and appointing outside alcaldes.

Notes:

Álvarez, Juan [Fray]. Declaration, 12 January 1706, in Bandelier; population numbers.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier. Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Rick Hendricks and John P. Wilson, The Navajos in 1705, 1996; chusma were non-combatants.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966; quotation on scalps from Chacón. Chacón described "the pueblos," did not specify which ones.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, in Bandalier; quotation from Cuervo.

When they mustered for the Spanish, they were with their own war captains. Within campaigns, they were commanded by pueblo leaders. In 1706, it was Domingo Romero Yaguaque of Tesuque who served as capitán mayor de la guerra. In 1708, Romero and Felipe of Pecos served Juan de Ulibarrí.

Scouts were almost always from the pueblos. Diego de Vargas used José López Naranjo as his lead against the Faraón in the Sandías in 1704. Roque de Madrid used him when they chased the Navajo west the follow year. Ulibarrí used the scout with Jean de l’Archevêque when they ventured onto the plains in 1706. In 1713, Naranjo was capitán mayor against the Navajo.

Warriors continued using their traditional methods. During the 1705 campaign, they scalped the Navajo men. Antonio Álvarez Castrillón said, there were:

"many more deaths that the Indian allies will have carried out among the women and chusma over the distance they covered on top of the mesa. This is their custom, and no matter how much I reproach them, they neither take heed nor pay attention unless Spaniards are present."

Post-battle rituals were maintained, at least until 1712 when José Chacón banned them. Then they continued surreptitiously.

He reported the pueblos: "keep the scalps taken from their enemies, the unfaithful enemies whom they kill in battle, bring them and dance publicly." He speculated on what happened later in the kivas where "they invoke the devil, and in his company and with his advice and suggestion they exhort one thousand errors."

What actually happened in the kivas was probably more subtle that the witchcraft imagined by Juan de la Peña, the Franciscan custodio in 1709, or by Chacón in 1712. The governors only knew they asked pueblo alcaldes to bring specified numbers of men. They had no idea if particular warriors were selected because they were the most experienced or were initiates who needed to prove themselves.

They certainly had no idea if there were any kinship or other special relationships between the men. Commanders only recorded the numbers from each pueblo on the muster rolls, not names. Sometimes, all that survives in documents is the total number of auxiliaries, or a mere acknowledgment they were present.

In 1706, Juan Álvarez estimated there were about 210 "Christian persons, large and small" at Santa Clara and 340 at San Juan. If one assumes 30% of the male population was the right age, and only 40% of the population was male after the battles of the Reconquest, there would still have been 25 available men at the one and 40 at the other. In 1704, Santa Clara’s quota, including war captains, was five, and San Juan’s six.

Commanders knew pueblo warriors painted themselves and wore feathers when they went into battle. Soldiers and settlers camped separately from auxiliaries. They had no idea what occurred before battles when men from different pueblos prepared themselves.

Cuervo believed the auxiliaries were "satisfied with the useful spoils of war." He didn’t recognize traditional male roles, social groups, and status hierarchies were being reinforced by opportunities to continue doing what ought to be done - punishing those who had harmed the pueblos - at a time when his regime might have been undermining traditional leaders by overseeing the elections of internal governors and appointing outside alcaldes.

Notes:

Álvarez, Juan [Fray]. Declaration, 12 January 1706, in Bandelier; population numbers.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Bandelier, Adolph F. A. and Fanny R. Bandelier. Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s campaign against the Navajo, republished in Rick Hendricks and John P. Wilson, The Navajos in 1705, 1996; chusma were non-combatants.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966; quotation on scalps from Chacón. Chacón described "the pueblos," did not specify which ones.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, in Bandalier; quotation from Cuervo.

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Navajo Raids

Diego de Vargas left Nuevo México believing local indios bárbaros fell into two groups: Athabaskan speakers and Shoshone speakers. Navajo and Apache were grouped together in the first, Ute and Comanche in the second.

When he returned in 1703, differences between bands were becoming clear. Navajo attacked from the north and west. Faraón Apache came from the east.

In 1704, de Vargas led a force against the Faraón in the Sandías that mustered in Bernalillo. The war captain from Santa Clara, Juan Roque, was there with four men. Lorenzo brought five men from San Juan.

By the time Francisco Cuervo arrived to replace de Vargas in 1705, the Navajo had become more dangerous. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso twice. He immediately stationed presidio troops at the most exposed points, including Santa Clara on the west side of the Río Grande.

In March, Roque de Madrid pursued them with 65 men. They included soldiers from the presidio, the men assigned to Santa Clara, and the militia. In August, Cuervo sent him north from San Juan to follow the Navajo into their homeland. He went through uncharted territory north of Taos and west of the Continental Divide. When he returned he remarked, "we could make war on them again with greater advantage than at present, because all the men are now experienced in this land, the ways in and out, and we would return with more food."

The Navajo had made peace with Cuervo, not with the entity called Nuevo México. José Chacón took over as governor in 1707 during a severe drought. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso in 1708. Madrid was dispatched with presidio forces, settlers from Santa Cruz, and auxiliaries from the three affected pueblos.

Navajo raids continued. They stole animals from Santa Clara in 1709. Chacón sent troops to no avail, and so did his successor, Juan Flores Mogollón. Soldiers now knew about the upper reaches of the Chama river and followed it directly. Madrid attacked again in March of 1714, and killed 30 Navajo. Raids stopped. Flores took away the pueblos’ guns in July.

Notes:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s 1705 campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; it gives no details on the men who mustered, refers to the local auxiliaries as Tewa, and lists a few men who were his staff. Only Naranjo was from Santa Cruz.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Vargas, Diego de. War edicts, 27 March-2 April, 1704, in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

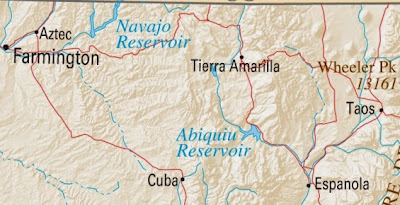

Map: United States Department of the Interior. Geological Survey. National Atlas of the United States of America. "New Mexico," 2004.

Hendricks and Wilson reconstructed Madrid’s 1705 route up the red line at the right (Route 68) to the first river (blue line). From there (Pilar) they went west to the next red line, the one under the "W."

They also traced Madrid’s route south along the Chama (the blue line north of Tierra Amarilla) down to the red road (Route 64), across that road west, then back south along the river towards Cuba. They ended at Zia.

Madrid called the land between what is now Tres Piedras and the Chama the Sierra Florida. It was the first time Spaniards had been there, and the pueblo warriors seem to have been beyond their usual range. Hendricks and Wilson think Madrid may have continued north to the Río de los Piños at the Colorado border, gone west, and down the Chama. They did not use the modern way over the Tusas mountains, Route 64.

When he returned in 1703, differences between bands were becoming clear. Navajo attacked from the north and west. Faraón Apache came from the east.

In 1704, de Vargas led a force against the Faraón in the Sandías that mustered in Bernalillo. The war captain from Santa Clara, Juan Roque, was there with four men. Lorenzo brought five men from San Juan.

By the time Francisco Cuervo arrived to replace de Vargas in 1705, the Navajo had become more dangerous. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso twice. He immediately stationed presidio troops at the most exposed points, including Santa Clara on the west side of the Río Grande.

In March, Roque de Madrid pursued them with 65 men. They included soldiers from the presidio, the men assigned to Santa Clara, and the militia. In August, Cuervo sent him north from San Juan to follow the Navajo into their homeland. He went through uncharted territory north of Taos and west of the Continental Divide. When he returned he remarked, "we could make war on them again with greater advantage than at present, because all the men are now experienced in this land, the ways in and out, and we would return with more food."

The Navajo had made peace with Cuervo, not with the entity called Nuevo México. José Chacón took over as governor in 1707 during a severe drought. They attacked San Juan, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso in 1708. Madrid was dispatched with presidio forces, settlers from Santa Cruz, and auxiliaries from the three affected pueblos.

Navajo raids continued. They stole animals from Santa Clara in 1709. Chacón sent troops to no avail, and so did his successor, Juan Flores Mogollón. Soldiers now knew about the upper reaches of the Chama river and followed it directly. Madrid attacked again in March of 1714, and killed 30 Navajo. Raids stopped. Flores took away the pueblos’ guns in July.

Notes:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Carson, Phil. Across the Northern Frontier, 1998.

Castrillón, Antonio Álvarez. Campaign journal for Roque Madrid’s 1705 campaign against the Navajo, republished in Hendricks.

Hendricks, Rick and John P. Wilson. The Navajos in 1705, 1996; it gives no details on the men who mustered, refers to the local auxiliaries as Tewa, and lists a few men who were his staff. Only Naranjo was from Santa Cruz.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, 1996 edition.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Vargas, Diego de. War edicts, 27 March-2 April, 1704, in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914.

Map: United States Department of the Interior. Geological Survey. National Atlas of the United States of America. "New Mexico," 2004.

Hendricks and Wilson reconstructed Madrid’s 1705 route up the red line at the right (Route 68) to the first river (blue line). From there (Pilar) they went west to the next red line, the one under the "W."

They also traced Madrid’s route south along the Chama (the blue line north of Tierra Amarilla) down to the red road (Route 64), across that road west, then back south along the river towards Cuba. They ended at Zia.

Madrid called the land between what is now Tres Piedras and the Chama the Sierra Florida. It was the first time Spaniards had been there, and the pueblo warriors seem to have been beyond their usual range. Hendricks and Wilson think Madrid may have continued north to the Río de los Piños at the Colorado border, gone west, and down the Chama. They did not use the modern way over the Tusas mountains, Route 64.

Labels:

01 Madrid,

02 Navajo,

02 San Juan 1-5,

02 Santa Clara 1-5

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Pueblo Relations

Diego de Vargas returned as governor of Nuevo México in 1703. It’s not clear if he realized how much the settlement had changed since he left in 1697. Pueblo relations were close to those between Natives and Spaniards in New Spain, and would become completely rationalized by the man who became governor in 1705, Francisco Cuervo.

Encomiendas were gone. The only residual was Cuervo’s expectation that "Christian Catholics" in the pueblos would take "care to till and cultivate the fields" for the "father minister" for the "regular maintenance of his person."

Repartimiento was nearly gone. The only labor quotas that survived were those imposed by governors for defense. Pueblos were required to send their best warriors for expeditions against bárbaros.

Wage labor had replaced both in the years immediately after Juan de Oñate trekked north and east from Nueva Vizcaya in 1588. Natives worked the silver mines and lived in homogenous communities surrounding Zacatecas and other mining towns. Some arrived as auxiliaries in local battles against nomadic bands in northern México.

Thus, the herbalist at San Juan, Juan, would have been paid for curing the women mentioned by Leonor Domínguez in 1708. Likewise, when she went for lime, she would have been expected to trade or pay for it. Disputes only arose when Españoles, like Felipe Morgana or Antonia Luján, felt they hadn’t received what they’d been promised.

The position of Catarina Luján, the lame woman accused of witchcraft by Leonor, is less clear. She testified "Father Fray Juan Minguez took this declarant to the said Town to clean his cell" in 1708. This may have been seen as "regular maintenance of his person" rather than paid work.

The pueblos assiduously defended their rights. In 1707 San Juan complained Roque de Madrid forced members to work on Sunday and was too authoritarian. It had the alcalde sign its complaint, but the governor, Jose Chacón, didn’t pursue it.

Friars later complained Chacón and his alcaldes were forcing people to work without pay. The viceroy sent a reprimand. His successor, Juan Flores Magollón, canvassed the pueblos in 1712. All said their members were paid for services, and none had been forcibly removed.

The major change in pueblo relations came with the use of auxiliaries. Oakah Jones noted that, before de Vargas left, he used warriors from one pueblo to attack another. When he died in 1704, he was using presidio, settler and pueblo troops together against common enemies. His earlier negotiations for submission had been converted into obligations of protection held by the pueblos.

Notes: See "Chronicles of Leonor" for more on Juan, Catarina Luján, Leonor Domínguez, Antonia Luján, and Felipe Morgana.

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978; on complaint against Madrid.

Bakewell, P. J. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico, Zacatecas 1546-1700, 1971.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Frank, Andre Gunder. Mexican Agriculture 1521-1630, 1979.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, collected by Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, included in Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett; quotation from Cuervo.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914; quotation from Luján.

Encomiendas were gone. The only residual was Cuervo’s expectation that "Christian Catholics" in the pueblos would take "care to till and cultivate the fields" for the "father minister" for the "regular maintenance of his person."

Repartimiento was nearly gone. The only labor quotas that survived were those imposed by governors for defense. Pueblos were required to send their best warriors for expeditions against bárbaros.

Wage labor had replaced both in the years immediately after Juan de Oñate trekked north and east from Nueva Vizcaya in 1588. Natives worked the silver mines and lived in homogenous communities surrounding Zacatecas and other mining towns. Some arrived as auxiliaries in local battles against nomadic bands in northern México.

Thus, the herbalist at San Juan, Juan, would have been paid for curing the women mentioned by Leonor Domínguez in 1708. Likewise, when she went for lime, she would have been expected to trade or pay for it. Disputes only arose when Españoles, like Felipe Morgana or Antonia Luján, felt they hadn’t received what they’d been promised.

The position of Catarina Luján, the lame woman accused of witchcraft by Leonor, is less clear. She testified "Father Fray Juan Minguez took this declarant to the said Town to clean his cell" in 1708. This may have been seen as "regular maintenance of his person" rather than paid work.

The pueblos assiduously defended their rights. In 1707 San Juan complained Roque de Madrid forced members to work on Sunday and was too authoritarian. It had the alcalde sign its complaint, but the governor, Jose Chacón, didn’t pursue it.

Friars later complained Chacón and his alcaldes were forcing people to work without pay. The viceroy sent a reprimand. His successor, Juan Flores Magollón, canvassed the pueblos in 1712. All said their members were paid for services, and none had been forcibly removed.

The major change in pueblo relations came with the use of auxiliaries. Oakah Jones noted that, before de Vargas left, he used warriors from one pueblo to attack another. When he died in 1704, he was using presidio, settler and pueblo troops together against common enemies. His earlier negotiations for submission had been converted into obligations of protection held by the pueblos.

Notes: See "Chronicles of Leonor" for more on Juan, Catarina Luján, Leonor Domínguez, Antonia Luján, and Felipe Morgana.

Athearn, Frederic J. A Forgotten Kingdom, 1978; on complaint against Madrid.

Bakewell, P. J. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico, Zacatecas 1546-1700, 1971.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530-1888, 1889.

Frank, Andre Gunder. Mexican Agriculture 1521-1630, 1979.

Jones, Oakah L. Pueblo Warriors and Spanish Conquest, 1966.

Rael de Aguilar, Alonso. Certification, 10 January 1706, collected by Adolph F. A. Bandelier and Fanny R. Bandelier, included in Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, volume 3, 1937, translated and edited by Charles Wilson Hackett; quotation from Cuervo.

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. Spanish Archives of New Mexico: Compiled and Chronologically Arranged, volume 2, 1914; quotation from Luján.

Sunday, May 17, 2015

War of Spanish Succession

1713 marks the end of the War of Spanish Succession. The war began when Charles II of Spain died in 1700, leaving no direct heir. His will and rules of seniority favored Philip V of the Bourbon House of France. Austria protested with war, and England seconded.

Among its many provocations was the monopoly for trade in Spanish ports. Portugal had returned the asiento in 1701, and Philip reawarded it to the Louis XIV. He, in turn, granted it to Jean-Baptiste Ducasse, then governor of a sugar colony, Saint-Dominique. The three, Ducasse, Louis and Philip, were to split the profits.

The asiento included the right to deliver African slaves to Veracruz for the lowland sugar plantations. The Council of the Indies thought France dangerous and impeded its implementation. Natives made no protest; they didn’t want that work. The new viceroy, the Duque de Albuquerque, signed off when he arrived in 1702. The Portuguese buttressed England and Austria in the war.

This time, the Iroquois, temporarily weakened by smallpox, declared themselves neutral. Native groups moved back into lands they’d been forced to abandon. The Tamora left the Peoria to live with the Cahokia in 1699. The next year, Rouensa and the Kaskaskia left Pimitéoui.

The French had two goals: securing control of the Mississippi river and gaining access to Spain’s silver mines in northern México. They still thought the Missouri river would take them to Santa Fé. It empties into the Mississippi between the Illinois and Kaskaskia rivers that come from the left bank. Cahokia lies between the confluence and the Kaskaskia.

The French minster for colonial affairs dispatched Pierre Le Moyne to resume La Salle’s search for the mouth of the Mississippi in 1698. Le Moyne had been born in Québec, worked as an independent fur trader, and fought the English at Hudson’s Bay. He built his first gulf fort, Maurepas, on Biloxi Bay in 1699. His second was Fort Louis de la Louisiane on the Mobile river.

At the same time, 1698, the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères sent priests into Illinois country from Québec The Jesuits had already organized a mission at Starved Rock under Jacques Gravier. They assigned Pierre-Gabriel Marest to him that year. After some jurisdictional spatting, the first group left François Buisson de Saint Cosme with the Cahokia and directed the rest of their men south towards Le Moyne.

Marest followed Rouensa and the Kaskaskia. He had been the Jesuit chaplain for Le Moyne’s Hudson’s Bay expedition. Rouensa later said he had moved his band at the request of the Louisiana governor.

Gravier joined Henri de Tonti’s delegation of Cahokia coureurs de bois going to Fort Maurepas in 1701 with a load of beaver pelts. Soon after, the Illinois settlements was sending dried bison ribs south.

Nearly simultaneously, Charles Juchereau was in Paris lobbying the French ministry for a concession to develop a tannery in Illinois country. He argued he could provide an alternative for coureurs then selling furs to the English. He left Montréal in 1702 with some thirty men to build a fort near the mouth of the Ohio river. After he died in the 1703 smallpox epidemic, the Cherokee attacked. Some survivors went to Fort Louis. Others became coureurs.

Canadian authorities complained about his activities, as did Père Marest. Le Moyne supported the concession. His wife was the daughter of Marie-Anne Juchereau. Jucheareau’s family had begun lending money to coureurs in Montreal in the 1690s. Tonti was a client in 1693.

Le Moyne died in 1706. France tried to regularize the gulf region with a proprietary grant to Antoine Crozat in 1712. He, the Spanish and the English all had to handle the consequences of Le Moyne’s policy of encouraging young men to learn native languages and explore the country.

The El Cuartelejo Apache killed a white man and his Pawnee wife in 1706. The booty included a French gun and powder, a kettle, coat, and red-lined cap. Four days later, Juan de Ulibarrí arrived from Santa Fé on another matter. It was the first Spanish expedition onto the plains and Le Moyne’s coureurs were already on the upper reaches of the Arkansas and Missouri rivers.

In Europe, each state maneuvered to capture territory from one of its enemies. The Treaty of Utrecht awarded the throne of Spain to the House of Bourbon and adjudicated land claims. Spain kept its colonies in the new world, but lost its non-peninsular territory in Europe.

France was not allowed to profit from its influence in Spain. The treaty stipulated the two crowns could not be consolidated as the Austrian and Spanish had been under the Hapsburg Charles V. It eliminated the French monopoly in the fur trade, and mandated it be opened in western Canada (Rupert’s Land) to Hudson’s Bay Company. England also won the monopoly for importing slaves to México. All commerce between Nuevo México and the French became illegal again.

Notes: The French minster for colonial affairs was Louis Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain. Pierre Le Moyne was the Sieur d'Iberville. Charles Juchereau was the Sieur de Saint Denis. Cairo, Illinois, is near his tannery. The War of Spanish Succession is called Queen Anne’s War in American history textbooks.

Caldwell, Norman W. "Charles Juchereau de St. Denys: A French Pioneer in the Mississippi Valley," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 28:563-579:1942.

Fortier, John. "Juchereau de Saint-Denys, Charles," in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, volume 2, 1982 revision.

Morrissey, Robert Michael. Empire by Collaboration, 2015.

Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade, 1997; on the asiento.

Thompson, Joseph J. "The Cahokia Mission Property," Illinois Catholic Historical Review 5:195-217:1922.

White, Richard. "The Louisiana Purchase and the Fictions of Empire," in Peter J. Kastor and François Weil, Empires of the Imagination, 2009.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Map: Shannon, "Map of Mississippi River," Wikimedia Commons, 5 April 2010.

Among its many provocations was the monopoly for trade in Spanish ports. Portugal had returned the asiento in 1701, and Philip reawarded it to the Louis XIV. He, in turn, granted it to Jean-Baptiste Ducasse, then governor of a sugar colony, Saint-Dominique. The three, Ducasse, Louis and Philip, were to split the profits.

The asiento included the right to deliver African slaves to Veracruz for the lowland sugar plantations. The Council of the Indies thought France dangerous and impeded its implementation. Natives made no protest; they didn’t want that work. The new viceroy, the Duque de Albuquerque, signed off when he arrived in 1702. The Portuguese buttressed England and Austria in the war.

This time, the Iroquois, temporarily weakened by smallpox, declared themselves neutral. Native groups moved back into lands they’d been forced to abandon. The Tamora left the Peoria to live with the Cahokia in 1699. The next year, Rouensa and the Kaskaskia left Pimitéoui.

The French had two goals: securing control of the Mississippi river and gaining access to Spain’s silver mines in northern México. They still thought the Missouri river would take them to Santa Fé. It empties into the Mississippi between the Illinois and Kaskaskia rivers that come from the left bank. Cahokia lies between the confluence and the Kaskaskia.

The French minster for colonial affairs dispatched Pierre Le Moyne to resume La Salle’s search for the mouth of the Mississippi in 1698. Le Moyne had been born in Québec, worked as an independent fur trader, and fought the English at Hudson’s Bay. He built his first gulf fort, Maurepas, on Biloxi Bay in 1699. His second was Fort Louis de la Louisiane on the Mobile river.

At the same time, 1698, the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères sent priests into Illinois country from Québec The Jesuits had already organized a mission at Starved Rock under Jacques Gravier. They assigned Pierre-Gabriel Marest to him that year. After some jurisdictional spatting, the first group left François Buisson de Saint Cosme with the Cahokia and directed the rest of their men south towards Le Moyne.

Marest followed Rouensa and the Kaskaskia. He had been the Jesuit chaplain for Le Moyne’s Hudson’s Bay expedition. Rouensa later said he had moved his band at the request of the Louisiana governor.

Gravier joined Henri de Tonti’s delegation of Cahokia coureurs de bois going to Fort Maurepas in 1701 with a load of beaver pelts. Soon after, the Illinois settlements was sending dried bison ribs south.

Nearly simultaneously, Charles Juchereau was in Paris lobbying the French ministry for a concession to develop a tannery in Illinois country. He argued he could provide an alternative for coureurs then selling furs to the English. He left Montréal in 1702 with some thirty men to build a fort near the mouth of the Ohio river. After he died in the 1703 smallpox epidemic, the Cherokee attacked. Some survivors went to Fort Louis. Others became coureurs.

Canadian authorities complained about his activities, as did Père Marest. Le Moyne supported the concession. His wife was the daughter of Marie-Anne Juchereau. Jucheareau’s family had begun lending money to coureurs in Montreal in the 1690s. Tonti was a client in 1693.

Le Moyne died in 1706. France tried to regularize the gulf region with a proprietary grant to Antoine Crozat in 1712. He, the Spanish and the English all had to handle the consequences of Le Moyne’s policy of encouraging young men to learn native languages and explore the country.

The El Cuartelejo Apache killed a white man and his Pawnee wife in 1706. The booty included a French gun and powder, a kettle, coat, and red-lined cap. Four days later, Juan de Ulibarrí arrived from Santa Fé on another matter. It was the first Spanish expedition onto the plains and Le Moyne’s coureurs were already on the upper reaches of the Arkansas and Missouri rivers.

In Europe, each state maneuvered to capture territory from one of its enemies. The Treaty of Utrecht awarded the throne of Spain to the House of Bourbon and adjudicated land claims. Spain kept its colonies in the new world, but lost its non-peninsular territory in Europe.

France was not allowed to profit from its influence in Spain. The treaty stipulated the two crowns could not be consolidated as the Austrian and Spanish had been under the Hapsburg Charles V. It eliminated the French monopoly in the fur trade, and mandated it be opened in western Canada (Rupert’s Land) to Hudson’s Bay Company. England also won the monopoly for importing slaves to México. All commerce between Nuevo México and the French became illegal again.

Notes: The French minster for colonial affairs was Louis Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain. Pierre Le Moyne was the Sieur d'Iberville. Charles Juchereau was the Sieur de Saint Denis. Cairo, Illinois, is near his tannery. The War of Spanish Succession is called Queen Anne’s War in American history textbooks.

Caldwell, Norman W. "Charles Juchereau de St. Denys: A French Pioneer in the Mississippi Valley," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 28:563-579:1942.

Fortier, John. "Juchereau de Saint-Denys, Charles," in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, volume 2, 1982 revision.

Morrissey, Robert Michael. Empire by Collaboration, 2015.

Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade, 1997; on the asiento.

Thompson, Joseph J. "The Cahokia Mission Property," Illinois Catholic Historical Review 5:195-217:1922.

White, Richard. "The Louisiana Purchase and the Fictions of Empire," in Peter J. Kastor and François Weil, Empires of the Imagination, 2009.

Ulibarrí, Juan de. Diary of expedition to El Cuartelejo, 1706, in Alfred B. Thomas, After Coronado, 1935.

Map: Shannon, "Map of Mississippi River," Wikimedia Commons, 5 April 2010.

Thursday, May 14, 2015

French and Indian Wars

René-Robert Cavelier, the Sieur de La Salle, heard the reports of Louis Joliet. He had migrated to Montréal from Rouen in 1666 and established himself as a fur trader. In 1680, he expanded his operations into Illinois country where he and Henri de Tonti built Fort Crèvceœur at the Peoria village Joliet had visited with Jacques Marquette. When Tonti left to build another fort near the Kaskaskia village, the men he left burned Crèvceœur after taking the food stores and ammunition. The Iroquois destroyed Starved Rock. The bands of the Illinois confederacy retreated west of the Mississippi.

The explorer returned in 1682 to rebuild Fort Crèvceœur at the head of navigation on the Illinois river. This time he brought guns and metal tools to trade for furs. Then he and Tonti left to complete the work of Joliet by following the Mississippi to its mouth. As they went, they built posts and made land grants to some of the Frenchmen who went with them, including Michael Accault.

La Salle left Tonti in Illinois while he returned to Paris to secure financing for a Mississippi colonization scheme. He and 300 settlers set sail for the Gulf in 1684. While they were floundering on the Texas coast, Tonti started down the Mississippi. When he failed to meet La Salle, he established a post with the Arkansas in 1686 and left Jean Couture in command.

By 1687, when La Salle was assassinated, many had died. Six straggled north to Tonti’s post and six took shelter with the Caddo-speaking Hasinai in what is now east Texas. Two of those, Jean l'Archevêque and Jacques Grollet, were ransomed by the Spanish in 1688. Two more, Pierre Meunier and Pierre Talon, were captured the next year.

L’Archevêque and Grollet were interrogated in Mexico City, then shipped to a Madrid jail in 1690. In 1692, during a lull in hostilities with France, l’Archevêque asked to be released. The Junta De Guerra de Indias took oaths of loyalty from him and Grollet, then dispatched them back to New Spain. Their enlistment with Diego de Vargas probably was not voluntary.

Meunier was used as an interpreter for Spanish missionaries to the Hasinai, before being sent north with de Vargas. He remained with the presidio at El Paso.

Jean Couture explored eastern tributaries of the Mississippi, went down to Florida, and visited in Charles Town where he made himself available to slave traders interested in adding furs to their export lists. In 1699, he took William Bond west, and the next year he led a group authorized by the governor, Joseph Blake. They made new alliances for slaves and deer skins with the Arkansas, renamed the Quapaw.

Tonti remained in Illinois country. In 1691 he built Fort Pimitéoui near Fort Crèvceœur and the Kaskaskia. Accault returned to the Pimitéoui area in 1693. He married the daughter of the Kaskaskia chief, Marie Rouensa the following year.

Notes: The gouverneur général of Nouvelle-France was Louis de Baude, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau. Crèvecoeur means broken heart. The Frenchmen were known by Spanish names in Nuevo Mexico: Juan de Archibeque, Pedro Meusnier, and Santiago Grole. The last evolved into Gurulé.

Morrissey, Robert Michael. Empire by Collaboration, 2015.

Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade, 1997.

Weddle, Robert S. "Meunier, Pierre," Texas State Historical Association website, posted 15 June 2010, revised 25 November 2013.

The explorer returned in 1682 to rebuild Fort Crèvceœur at the head of navigation on the Illinois river. This time he brought guns and metal tools to trade for furs. Then he and Tonti left to complete the work of Joliet by following the Mississippi to its mouth. As they went, they built posts and made land grants to some of the Frenchmen who went with them, including Michael Accault.

La Salle left Tonti in Illinois while he returned to Paris to secure financing for a Mississippi colonization scheme. He and 300 settlers set sail for the Gulf in 1684. While they were floundering on the Texas coast, Tonti started down the Mississippi. When he failed to meet La Salle, he established a post with the Arkansas in 1686 and left Jean Couture in command.

By 1687, when La Salle was assassinated, many had died. Six straggled north to Tonti’s post and six took shelter with the Caddo-speaking Hasinai in what is now east Texas. Two of those, Jean l'Archevêque and Jacques Grollet, were ransomed by the Spanish in 1688. Two more, Pierre Meunier and Pierre Talon, were captured the next year.

L’Archevêque and Grollet were interrogated in Mexico City, then shipped to a Madrid jail in 1690. In 1692, during a lull in hostilities with France, l’Archevêque asked to be released. The Junta De Guerra de Indias took oaths of loyalty from him and Grollet, then dispatched them back to New Spain. Their enlistment with Diego de Vargas probably was not voluntary.

Meunier was used as an interpreter for Spanish missionaries to the Hasinai, before being sent north with de Vargas. He remained with the presidio at El Paso.

Jean Couture explored eastern tributaries of the Mississippi, went down to Florida, and visited in Charles Town where he made himself available to slave traders interested in adding furs to their export lists. In 1699, he took William Bond west, and the next year he led a group authorized by the governor, Joseph Blake. They made new alliances for slaves and deer skins with the Arkansas, renamed the Quapaw.

Tonti remained in Illinois country. In 1691 he built Fort Pimitéoui near Fort Crèvceœur and the Kaskaskia. Accault returned to the Pimitéoui area in 1693. He married the daughter of the Kaskaskia chief, Marie Rouensa the following year.

Notes: The gouverneur général of Nouvelle-France was Louis de Baude, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau. Crèvecoeur means broken heart. The Frenchmen were known by Spanish names in Nuevo Mexico: Juan de Archibeque, Pedro Meusnier, and Santiago Grole. The last evolved into Gurulé.

Morrissey, Robert Michael. Empire by Collaboration, 2015.

Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade, 1997.

Weddle, Robert S. "Meunier, Pierre," Texas State Historical Association website, posted 15 June 2010, revised 25 November 2013.

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

Early Slave Trade

Mariana of Austria, regent for Charles II, oversaw Spain from 1665 to 1696. Those years coincided with English and French wars against the weakened country that spilled onto this continent as the first French and Indian Wars. They began with King Phillips’s War (1675-1678) and continued with King William’s War waged (1688-1697).

King Phillip’s war accelerated a chain of displacements in the north that began in 1648 when the Dutch provided Iroquois with arms to abet their expansion into the fur trade. The Iroquois decimated France’s partners, the Huron. The Ottawa replaced them around Michilimackinac in the straits between lakes Huron and Michigan.

A routed Erie band, the Westo, and a Shawnee group, the Savannah, headed south. The Sioux-speaking Osage and Kansa abandoned the area south of the Ohio river for that south of the Missouri. Potawatomi shifted west. When they entered the Green Bay area of Wisconsin, others migrated farther west, until they reached the Sioux who would not be moved.

In the same years, the Dutch transferred their knowledge of sugar production from Brazil to English planters in Barbados. By 1680, 80% of the island was devoted to cane. Planters imported everything, even fire wood, from the Virginia colony.

Life spans were short on the island, labor scarce. Small pox was a constant menace in a society filled with newcomers and serviced by ships that visited many ports. In 1670, Caribbean settlers in Carolina teamed with the Westo to raid other southeastern tribes. Captives were sold into slavery in the sugar colonies. Charles Town traders replaced the Westo with the Savannah in 1680.

Jesuit missionaries followed their charges. In 1673 they assigned Jacques Marquette to the expedition sponsored by the governor general of Nouvelle-France to explore the Mississippi river. Everywhere he and Louis Joliet stopped, they saw evidence of the burgeoning trade in captives.

At a Peoria village in Illinois country the men possessed guns "to procure Slaves; these they barter, selling them at a high price to other Nations, in exchange for other Wares."

Farther down the Mississippi, they saw natives, probably Chickasaw, on the left bank with guns, "hatchets, hoes, knives, beads, and flasks of double glass" for their powder.

Next they met victims of the trade. The Arkansas, who lived at the confluence of that river from the west, existed on corn and dog meat because they didn’t dare go hunting or gathering. The warriors wanted to kill them for their guns, but sharing the calumet had placed them under the chief’s protection. The band already had hatchets, knives, and beads.

Once Marquette and Joliet were told the river went to the Gulf of Mexico, they realized the area to the south was controlled by the Spanish. To get there, they would pass through "Savages allied to The Europeans, who were numerous, and expert in firing guns, and who continually infested the lower part of the river."

On their return, they followed the Illinois river north toward Lake Michigan. On the way the men stopped at the Kaskaskia’s Grand Village near Starved Rock. Marquette died from dysentery before he could return to them. His journal was published a few years later in the Jesuit Relations.

Notes: For more on the origins of sugar cane and Barbados, see post for 30 August 2009. The northern Iroquois wars also are called the Beaver Wars.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899; Dablon was Marquette’s superior and had a copy of his journal.

Smith, Marvin T. Archaeology of Aboriginal Cultural Change in the Interior Southeast, 1987; he identified the Westo as displaced Erie.

Map: Charles Edward, map of the location of major tribes involved in the Beaver Wars in 1648, Wikimedia Commons, 15 November 2008. The boundaries of the English colonies weren’t as distinct then as they are shown, especially on the western sides.

King Phillip’s war accelerated a chain of displacements in the north that began in 1648 when the Dutch provided Iroquois with arms to abet their expansion into the fur trade. The Iroquois decimated France’s partners, the Huron. The Ottawa replaced them around Michilimackinac in the straits between lakes Huron and Michigan.

A routed Erie band, the Westo, and a Shawnee group, the Savannah, headed south. The Sioux-speaking Osage and Kansa abandoned the area south of the Ohio river for that south of the Missouri. Potawatomi shifted west. When they entered the Green Bay area of Wisconsin, others migrated farther west, until they reached the Sioux who would not be moved.

In the same years, the Dutch transferred their knowledge of sugar production from Brazil to English planters in Barbados. By 1680, 80% of the island was devoted to cane. Planters imported everything, even fire wood, from the Virginia colony.

Life spans were short on the island, labor scarce. Small pox was a constant menace in a society filled with newcomers and serviced by ships that visited many ports. In 1670, Caribbean settlers in Carolina teamed with the Westo to raid other southeastern tribes. Captives were sold into slavery in the sugar colonies. Charles Town traders replaced the Westo with the Savannah in 1680.

Jesuit missionaries followed their charges. In 1673 they assigned Jacques Marquette to the expedition sponsored by the governor general of Nouvelle-France to explore the Mississippi river. Everywhere he and Louis Joliet stopped, they saw evidence of the burgeoning trade in captives.

At a Peoria village in Illinois country the men possessed guns "to procure Slaves; these they barter, selling them at a high price to other Nations, in exchange for other Wares."

Farther down the Mississippi, they saw natives, probably Chickasaw, on the left bank with guns, "hatchets, hoes, knives, beads, and flasks of double glass" for their powder.

Next they met victims of the trade. The Arkansas, who lived at the confluence of that river from the west, existed on corn and dog meat because they didn’t dare go hunting or gathering. The warriors wanted to kill them for their guns, but sharing the calumet had placed them under the chief’s protection. The band already had hatchets, knives, and beads.

Once Marquette and Joliet were told the river went to the Gulf of Mexico, they realized the area to the south was controlled by the Spanish. To get there, they would pass through "Savages allied to The Europeans, who were numerous, and expert in firing guns, and who continually infested the lower part of the river."

On their return, they followed the Illinois river north toward Lake Michigan. On the way the men stopped at the Kaskaskia’s Grand Village near Starved Rock. Marquette died from dysentery before he could return to them. His journal was published a few years later in the Jesuit Relations.

Notes: For more on the origins of sugar cane and Barbados, see post for 30 August 2009. The northern Iroquois wars also are called the Beaver Wars.

Marquette, Jacques. Journal included in Claude Dablon’s "Le Premier Voÿage Qu’a Fait Le P. Marquette vers le Nouveau Mexique," translated by Reuben Gold Thwaites in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, volume 59, 1899; Dablon was Marquette’s superior and had a copy of his journal.

Smith, Marvin T. Archaeology of Aboriginal Cultural Change in the Interior Southeast, 1987; he identified the Westo as displaced Erie.

Map: Charles Edward, map of the location of major tribes involved in the Beaver Wars in 1648, Wikimedia Commons, 15 November 2008. The boundaries of the English colonies weren’t as distinct then as they are shown, especially on the western sides.

Sunday, May 10, 2015

Horse Questions

Does anyone know anything about the sources of the horses for the Santa Fé presidio? Were they mares, geldings, or stallions? The moors liked mares because they could be trained to keep quiet during surprise attacks. Medieval knights preferred chargers. The US cavalry eventually used geldings.

Francisco Cuervo ordered 600 be sent to Santa Fé in 1705. This is not the same thing as ordering 600 tanks be shipped. Some foreman can’t just put on an extra shift to meet demand. It takes eleven months to produce a foal, and it make be two more years before it can be trained. During that time it needs pasturage and water.

Where were these breeding farms? Did they have special contracts with the government?

Training required skilled individuals. The greater the number of horses, the greater the number of trainers. Who were they in northern México? Natives or Spaniards?

Leave a comment below or send an email to nasonmcormic@cybermesa.com. You may need to have your email application open for the direct link to work.

Francisco Cuervo ordered 600 be sent to Santa Fé in 1705. This is not the same thing as ordering 600 tanks be shipped. Some foreman can’t just put on an extra shift to meet demand. It takes eleven months to produce a foal, and it make be two more years before it can be trained. During that time it needs pasturage and water.

Where were these breeding farms? Did they have special contracts with the government?

Training required skilled individuals. The greater the number of horses, the greater the number of trainers. Who were they in northern México? Natives or Spaniards?

Leave a comment below or send an email to nasonmcormic@cybermesa.com. You may need to have your email application open for the direct link to work.

Thursday, May 07, 2015

Miocene Española

Our major landmarks appeared in the Miocene that lasted from 23 to 5.3 million years ago. It’s hard to visualize a time when the land was relatively level with the surrounding Santa Fé, Pajarito, Colorado, and Taos plateaus. The surface would no longer have been the smooth water bed left by the retreating Western Inland Sea.

In the preceding Eocene that began 56 million years ago, the smooth edge of the Farallon plate had bumped into the buried remains the Yavapai-Mazatzal boundary. When the Picurís-Pecos fault intersected the Embudo fault, faults multiplied. The central Sangre de Cristo from Santa Fé north to Picurís began sinking while the two ends, Taos and Albuquerque, rose.

Shari Kelley and Ian Duncan have found evidence the Sandías and Truchas range were lifting again 35 million years ago, in the early Oligocene. The Picurís range recovered, and began rising a million years later.

A chunk of rock near Peñasco collapsed between the Pilar-Vadito fault on the northwest and the Santa Barbara on the southeast. The Jicarilla fault ran around the east end. The oldest surface rocks we have in this area are siltstone, sandstone, mudstone and claystone washed down from Peñasco.

These gravels cover Los Barrancos, a furrowed ridge skirted on its east by the road to Santa Fé. It’s laced with north-south fault lines starting above the modern Pojoaque river, crossing highway 84, and continuing across the Santa Cruz river. They’ve been roughly dated to the middle Miocene, 14.5 to 5 million years ago.

Coarser rocks from the Peñasco Embayment formed the bad lands on the east side of the valley north of the Santa Cruz. Perhaps they were the wash from that unnamed river, perhaps its course changed. Cobbles also spread over an old dune field in the north that had begun retreating between 11.5 and 9 million years ago.

The rock underlying the Española Basin dropped along the Pajarito fault. The half graben stayed connected on the east, tilting the block to the west and north. When it fell, the effects reverberated along the Embudo fault that runs northeast from the northern end of the valley.

Then the volcanos began. In the Arroyo Seco valley east of Los Barrancos, Ted Galusha and John Blick counted 37 layers of ash in the surrounding rocks. Tchicoma was formed between 7 and 3 million years ago.

Volcanism continued into the Pliocene era that began 5.333 million years ago. The southern Black Mesa formed about 4.4 million years ago, but the magma cooled in its neck, stopping the flow and sending it elsewhere in the Jémez. During the Ice Age, the surrounding cover disappeared, leaving the stem and a slope of debris to one side.

Rifting moved north and east. The Taos Plateau volcanic field became active about 4.5 million years ago. It threw lava that landed on that old dune field, capping the northern Black Mesa between 3.8 and 3.3 million years ago.

While the volcanos were spewing ash in the west, life continued on the other side of the basin. Grasses had multiplied in the Miocene and so did the animals that fed on them. The now extinct forms of camels, horses and rhinoceroses replaced the dinosaurs that had been lost at the end of Cretaceous mentioned in the last post.